“We do recover”: More evidence that tens of millions of adults in the United States have recovered from a substance use problem

Substance use disorders are chronic medical conditions for some, requiring ongoing, comprehensive care. At the population level, though, they are characterized by varying levels of severity, from mild to severe distress and impairments in functioning. In parallel, many people are in remission from SUD, the majority of whom have milder symptoms and can get well without any formal treatment. Research on substance use problem resolution has tended to focus on one end of the severity spectrum or the other, though population studies that span all levels of severity can help to broadly inform treatment and recovery support service knowledge and policies. In this study, the authors use a national survey to estimate the number of adults in the United States who have had a substance use problem in their lifetime and the percentage of those adults who have resolved their substance use problem.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Approximately 20 million adults in the United States currently meet criteria for a substance use disorder (SUD), which has been recognized as a chronic brain disease for those with more severe variants of the disorder. On an annual basis in the U.S., an estimated 95,000 people die from alcohol-related causes and, in 2019, it is estimated that more than 70,000 people died from a drug overdose. Despite these stark numbers, studies have reported that most people with alcohol use disorder experience remission – no SUD symptoms for 12 or more continuous months – and even a subset of those with a heroin use disorder will have a self-limiting illness and can enter remission without the need for ongoing treatment. Many of these people initiated SUD remission without treatment (also known as natural recovery).

Very few studies have examined those who have resolved a substance use problem. One nationally-representative survey (i.e. able to derive national estimates from the study), found that nearly 1 in 10 adults in the U.S. had resolved a significant alcohol or other drug problem, and half of those identified as being “in recovery”. However, little is known about those that have resolved a problem compared with those that currently have a substance use problem. More data on the differences between individuals with substance use problems who resolve or have not yet resolved their problem can offer key insights of treatment and recovery support service policies in the U.S.

In this study, the researchers used a national survey to estimate the number of adults in the United States who have had a substance use problem in their lifetime and the percentage of those adults who have resolved their substance use problem. They also examined sociodemographics and substance use histories that predict recovery from a substance use problem. Study findings can highlight characteristics that predict resolving a substance use problem and inform the expansion of treatment and recovery support services.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a secondary, cross-sectional analysis of an annual, nationally-representative survey of the U.S. population, called the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), that assessed both lifetime recognition of and recovery from a substance use problem. The NSDUH is an annual survey conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) that provides current estimates and trends on substance use as well as mental health and substance-related issues in the United States. The survey consists of an in-person interview and has a complex design that allows for national estimates to be derived from the responses of study participants. The research team used data from the 2018 NSDUH survey, in which 43,026 adults aged 18 and older participated.

Figure 1.

The analysis also used a new set of similar questions asking study participants about both lifetime recognition of and recovery from a mental health problem. In addition to these new questions on substance use and mental health, the NSDUH collects a wide range of data on sociodemographics, lifetime and past-year substance use profiles, and substance use treatment histories.

The research team first estimated the overall percentage of adults ever reporting a substance use problem (answered ‘yes’ to Question #1) and, among these adults, the percentage that reported recovery of a substance use problem (answered ‘yes’ to both Question #1 and Question #2). A statistical technique (known as multivariable logistic regression) was used to examine sociodemographic and mental health characteristics associated with being in recovery among adults who reported ever having a substance use problem.

Next, authors divided those who reported ever having a substance use problem into two groups based on self-reported recovery status: ‘In Recovery’ (answered ‘yes’ to both Question #1 and Question #2) and ‘Not In Recovery’ (answered ‘yes’ to Question #1 and ‘no’ to Question #2). Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine substance use histories among adults ever having a substance use problem by self-reported recovery status, controlling for sociodemographic and mental health characteristics. This statistical control was done to try and isolate the effect of substance use histories on self-reported recovery status.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

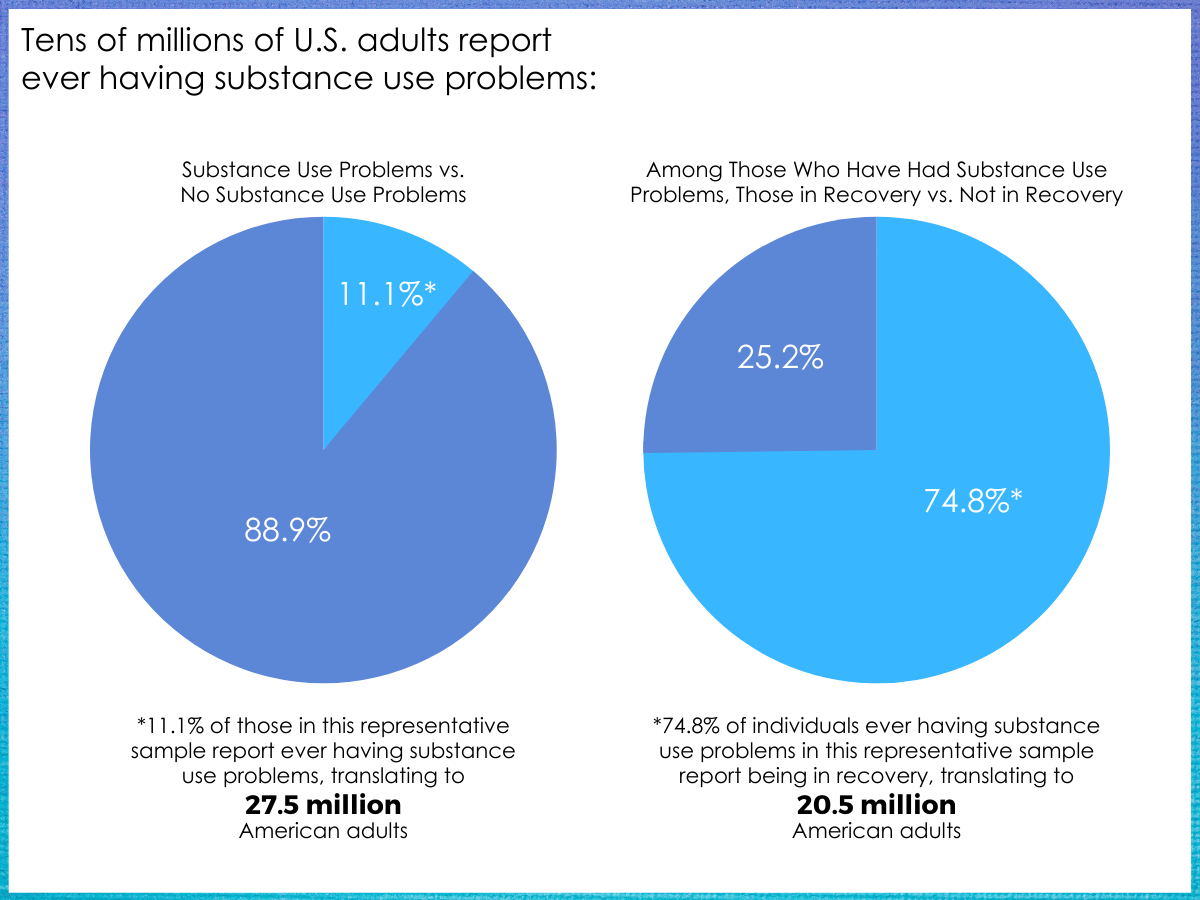

Tens of millions of U.S. adults report that they have recovered from a substance use problem.

Overall, 11.1% of the sample reported ever having a substance use problem, which translates to approximately 27.5 million adults in the United States. Of those reporting a substance use problem in their lifetime, 74.8% reported that they were in recovery or recovered from their substance use problem, translating to approximately 20.5 million adults in the United States.

Figure 2.

History of a mental health problem was associated with an increased likelihood of also having a substance use problem.

Among adults with a lifetime mental health problem, but not in recovery from this problem, 31.9% reported ever having a substance use problem. Among adults in recovery from a lifetime mental health problem, 29.7% reported ever having a substance use problem. This is compared to only 7.0% ever having a substance use problem among those that reported never having a mental health problem in their life.

Certain sociodemographic characteristics and mental health problem status increased or decreased the odds of recovering from a substance use problem.

Among those with a lifetime substance use problem, those that were age 50 and older, lived in a non-metro/rural area, and were in recovery from a mental health problem were more likely to report being in recovery from a substance use problem, whereas those that identified as non-Hispanic black and were not in recovery from a lifetime mental health problem were less likely to report being in recovery from a substance use problem.

Certain substance use profiles and history of substance use treatment were associated with recovery status.

Compared with those not in recovery, those in recovery were less likely to report past-year use of a wide range of substances including alcohol, marijuana, hallucinogens, cocaine, methamphetamine, sedative/tranquilizer misuse, and stimulant misuse. Those in recovery were more likely to report lifetime injection use and were twice as likely to have used SUD treatment in the past-year and in their lifetime, although 60% of those in recovery did not receive SUD treatment. Notably, 32% of those in recovery reported past-month binge drinking (4+ or 5+ drinks on one occasion for females and males, respectively) and 31% reported past-year marijuana use.

Regardless of recovery status, those that report a lifetime substance use problem have a high prevalence of tobacco use and nicotine dependence.

More than 90% of those with a lifetime substance use problem reported ever using tobacco, about half reported using tobacco in the past year, and almost 20% had nicotine dependence based on the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale. These percentages were similar regardless of recovery status.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study estimates that 11.1% of adults in the U.S., translating to 27.5 million people, have had a substance use problem in their lifetime and that 74.8% – 8.3% of the total US adult population – or 20.5 million adults are in recovery or have recovered from this problem. Having a resolved mental health problem and receiving substance use treatment increased the likelihood that a person reported recovery from a recognized substance use problem in their lifetime, whereas having an unresolved mental health problem, identifying as non-Hispanic black, and past-year use of a wide range of substances decreased this likelihood.

Findings from this study, along with other nationally representative studies, make clear that there are tens of millions of people in the United States who have resolved a significant alcohol or other drug problem. This goes against the cultural narrative, where substance use problems are often described as chronic, relapsing conditions, thus implying such affected individuals can never get and stay well. These findings corroborate findings from the National Recovery Study,a similar cross-sectional study (i.e. observes a person at one point in time) that examined those who have resolved a substance use problem in more detail. Future longitudinal research (i.e. follows a person over time) will provide greater insight and confirmation into these findings.

An interesting finding from this study was that those who reported being in recovery from a substance use problem were twice as likely to have received SUD treatment in the past year and over their lifetime compared with those who were not in recovery. However, only 40% of those who had recovered from a substance use problem had ever received SUD treatment. Taken together, these data suggest that treatment may help a person resolve an alcohol or drug problem, but the majority of people will recover without using formal treatment, either through other pathways of recovery (e.g. mutual-help organizations) or without using any formal services whatsoever (i.e. natural recovery). Although not analyzed in this study, prior research suggests that those able to recover without the use of any external service supports generally tend to have less severe addiction problem histories.

Those in recovery were more likely to report lifetime injection drug use compared with those who are not in recovery. Substance use problems are likely to be on a spectrum, from a severe and chronic SUD with many substance-related consequences to more discrete episodes of binge drinking that may have led to a family or legal consequence. Those with more severe substance use problems may be more likely to suffer more severe and cumulative consequences making it more likely, in turn, that they would seek SUD treatment, increasing the chances of resolving their problem. This also exposes them to the idea of abstinence and in adopting a social recovery identity. This may partially explain the decreased likelihood of those in recovery to report past-year substance use compared with those who are not in recovery.

Only 7.0% of those without a lifetime mental health problem reported ever having a substance use problem whereas more than 30% of those with a history of a mental health problem reported ever having a substance use problem. This finding parallels with the literature on the frequent comorbidity of substance use disorders and mental illness, termed ‘co-occurring disorders’ or ‘dual diagnosis’. Notably, those who are in recovery from a mental health problem were more likely to report recovery from a substance use problem while those not in recovery from a mental health problem were less likely to report recovery from a substance use problem. These findings emphasize the need to improve care for those with co-occurring disorders, possibly through integration of substance use and mental health treatment, and highlight the potential synergistic effect of treating a mental health condition when a person also has, or is at risk of developing, a substance use disorder. The process of supporting recovery from a substance use problem may have overlapping effects that also support recovery from a mental health problem.

A finding warranting more attention in this study was that, among those who ever reported a substance use problem, non-Hispanic black individuals were less likely to be in recovery from this problem compared to non-Hispanic white individuals, despite reporting lower rates of lifetime substance use problems. Understanding the exact reasons for this difference related to race/ethnicity in reporting recovery status is important as they could reflect discriminatory access to services.

Both lifetime and past-year tobacco use as well as past-month nicotine dependence among those who have ever had a substance use problem was higher than the general population, regardless of recovery status. Other research suggests that those who have recently resolved a substance use problem may show greater readiness to engage in smoking cessation compared with previous generations, and many people stopped smoking before reporting substance use problem resolution. Taken together, these findings suggest that smoking cessation programs targeted to both those currently experiencing and those recently resolving a substance use problem may improve population health and decrease healthcare burden.

Although those in recovery were less likely to report past-year use of a wide range of substances, 32% reported past-month binge drinking and 31% reported past-year marijuana use – just as 40% of the National Recovery Study sample that identified as being “in recovery” were using one or more substances. This goes against the historical and cultural grassroots meaning of “recovery” as typically requiring abstinence from all substances. Thus, from a public health perspective, encouraging the largest possible swath of individuals with substance use problems to reduce or quit substance use is likely to require a framework that might include, but also expands upon this common cultural understanding. Furthermore, research is needed to better understand how individuals perceive substance use problems, treatment-seeking, and recovery identity, especially across sociodemographic groups so that services and linkages to these services can be tailored to specific populations.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The NSDUH likely underestimates rates of substance use problems. Only non-institutionalized populations are represented in the annual survey, meaning that those who are experiencing homelessness and those that are incarcerated are not represented, two groups that are disproportionately impacted by substance use problems. In addition, the NSDUH relies on self-report, which introduces recall and social desirability bias.

- There may be limitations in the constructs being measured in this study. Study participants may misinterpret the question asked to assess lifetime substance use problem recognition. For example, participants may interpret Question #1 as meaning ‘used to have’ a substance use problem and would answer ‘no’ if they are currently experiencing a substance use problem. Also, there is no way to know how respondents define ‘recovery’ or ‘recovered’.

- Since this is a cross-sectional study and there are only two added questions to the NSDUH on lifetime substance use problem recognition and recovery, there is no way to know the duration of recovery from a substance use problem or whether individuals were in recovery at one time and the substance use problem reemerged. Nor is the study able to examine patterns for specific substances used.

- Problem recognition of a substance use problem and a clinical diagnosis of a substance use disorder may be very different for study participants. For example, a person may answer ‘yes’ to ever having a substance use problem because of a legal consequence for driving while intoxicated but may not fit the clinical definition of a substance use disorder.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Not everyone with a substance use problem may need treatment, but individuals with more challenges and life-impacting substance problems (e.g., injection drug use, co-occurring mental health condition, opioid versus cannabis as substance of choice) may increase their chances of problem resolution by seeking formal services with medical and other health care professionals.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Substance use problems occur on a spectrum of severity. Thus, individualized treatment can increase a person’s chance of achieving recovery from a moderate or severe substance use problem, but many individuals achieve problem resolution without formal treatment, seeking other pathways of recovery (e.g. mutual-help organizations or harm reduction/moderation of substance use) or they initiate recovery without any formal services (i.e. natural recovery). Those with co-occurring mental health conditions may warrant care that can address their substance use and mental health simultaneously. Given that many of these individuals smoke, embedding smoking cessation services in the variety of treatment and recovery support services will help patients to access and benefit from smoking cessation.

- For scientists: More research is needed to better understand perceived substance use problems, treatment-seeking, and recovery identity, especially across sociodemographic groups. In addition, longitudinal studies that examine recovery trajectories after problem resolution, and identification and intervention for those at risk for recurrence of problems, would provide greater insight into this population.

- For policy makers: Despite the increase in drug overdose deaths, tens of millions of people in the U.S. have recovered from a substance use problem, with the majority of this population not using formal treatment services. While policies to expand treatment and recovery support services are likely a fruitful endeavor, funding to support research on individuals who resolved an alcohol or drug problem without formal treatment could inform policies that maximize outcomes and enhance the likelihood of more rapid alcohol/drug problem resolution for those who do not seek services – which makes up a majority of those with substance use disorders. Understanding and addressing the exact nature of any potential barriers and facilitators to increase access to, and utilization of, treatment and recovery support services for non-Hispanic black individuals may be warranted, and integration of SUD treatment with mental health treatment will likely improve outcomes.

CITATIONS

Jones, C.M., Noonan, R.K., Compton, W.M. (2020). Prevalence and correlates of ever having a substance use problem and substance use recovery status among adults in the United States, 2018 [Epub ahead of print]. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 214, 108169. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108169