New…and improved? The latest studies on injectable buprenorphine for opioid use disorder

Suboxone is a first-line treatment for opioid use disorder. The need to take it daily, however, increases the risk that someone will miss a dose. Suboxone misuse and diversion also remain prominent concerns. Novel, FDA-approved injection formulations of buprenorphine, the active ingredient in Suboxone, were designed to address these potential drawbacks. Two recent studies show that injection buprenorphine outperforms a placebo injection and does as well as daily sublingual Suboxone.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Buprenorphine (often prescribed in a formulation with naloxone, which we refer to here as the brand name Suboxone for convenience given that it is most commonly known that way in the United States) is a first-line treatment for opioid use disorder. Suboxone helps reduce opioid use at doses of 16 mg or greater. Its receipt in large health care and criminal justice systems is associated with reductions in opioid overdose of 50% or more (also see here). There are several ways in which the benefits of Suboxone could be enhanced, including more consistent medication engagement (i.e., medication adherence), as well as reducing the frequency with which it is used at different amounts than prescribed (i.e., misuse) or used by others without a prescription (i.e., diversion). There may be advantages also to reducing the overall flow of opioids into communities, even medications like Suboxone, where it can cause harm (e.g., accidental ingestions), provided this does not make Suboxone any less accessible for those who need it. Buprenorphine injections (including two formulations marketed in the United States as Sublocade or Brixadi) may be able to address these problems and therefore enhance the overall public health impact of Suboxone. Two recent randomized clinical trials tested the benefits of buprenorphine injections on opioid use. In one, Haight and colleagues tested two buprenorphine injection protocols against a placebo injection. In another, Lofwall and colleagues tested buprenorphine injections against daily Suboxone, the most commonly prescribed buprenorphine formulation in the United States. This summary provides overviews of both studies.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Both studies were randomized controlled trials where buprenorphine injections were tested against either a placebo injection or the standard of care – daily Suboxone.

- READ MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

In the Haight study, 504 individuals with moderate/severe opioid use disorder (based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, or DSM 5) were all initially started on daily Suboxone (8-24 mg) for 2 weeks and then randomized to either 1) buprenorphine injection plus placebo sublingual tablets (n = 213) or Suboxone plus placebo injection (n = 215); 2) two monthly injections of 300mg buprenorphine and four monthly injections of 100mg buprenorphine (n = 203); or 3) placebo injections (n = 100). They received no buprenorphine injection or placebo once randomized to buprenorphine injections or placebo injection. Authors delivered medication treatment at outpatient sites around the U.S. and all participants received weekly “individual drug counseling”, a psychosocial treatment including substance use monitoring, problem solving, and discussions of engagement with community–based resources such as 12-step mutual-help organizations. This psychosocial approach was the best performing therapy in a prior study of cocaine use disorder, but was delivered twice weekly in that study compared to once a week or less often in this study. The study excluded those with a current diagnosis for any condition requiring opioid treatment (e.g., chronic pain), as well as moderate/severe alcohol use disorder in all cases, and cocaine use disorder or cannabis use disorder only if the individual’s urine screen was positive for cocaine or cannabis. The primary outcome was percentage of weeks opioid-free based on urine drug screens and self–reported substance use. Any missed drug screens were counted as positive. Authors also examined whether buprenorphine injections helped an individual achieve at least 80% weeks opioid-free.

The Lofwall study was also conducted over 24 weeks (i.e., 6 months) at outpatient clinical sites in the U.S. and participants were also diagnosed with moderate/severe opioid use disorder based on DSM 5. After being started on Suboxone to make sure individuals could tolerate the medication, 428 individuals were randomized to either 1) buprenorphine injection plus placebo sublingual tablet (n = 213) or Suboxone plus placebo injection (n = 215). Injections were administered weekly for the first 12 weeks and monthly for the next 12 weeks. Unlike the Haight study where individuals had fixed injection doses of 300mg or 100mg, in the Lofwall study buprenorphine doses were flexible at 64, 96, 128, or 160 mg which is analogous to Suboxone doses of 8,16, and 24 mg per day. Like the Haight study, both groups received individual drug counseling – weekly for the first 12 weeks and then monthly for the next 12 weeks. Although participants commonly used non-opioid substances when they entered the study (about 70% had some other substance use at baseline), authors did not exclude individuals with other substance use disorders. They did exclude individuals with current suicidal ideation/behavior. The primary outcome was mean percentage of opioid-free drug screens. The secondary outcome was whether an individual was a “responder”, defined as no opioid use (based on drug screen and self-report) at week 12, in two of the three assessments at weeks 9-11, and for five of the six assessments from weeks 12-24.

It is worth noting that 30-35% of individuals discontinued from study participation at some point — they did not finish the 6-month trial – but all individuals were included in the primary analyses that we summarize below (i.e., “intent to treat” analyses).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Buprenorphine injections lead to similar reductions in opioid use compared to daily Suboxone

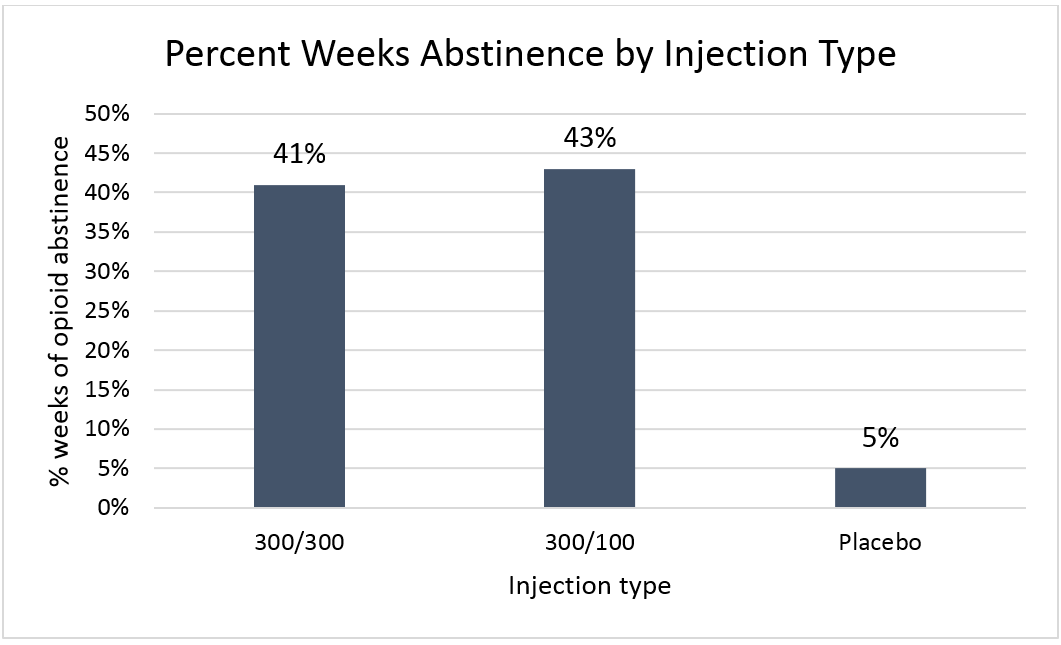

In the Haight study as illustrated in the figure below, both buprenorphine injection protocols, where participants received 300mg buprenorphine injections for six months (i.e., “300/300”) and where participants received 300mg buprenorphine injections for two months and then 100mg buprenorphine injections for four months (i.e., “300/100), had similar opioid free weeks. Both groups outperformed placebo injections.

Figure 1.

Buprenorphine injection participants were also more likely to have at least 80% of weeks in the study opioid-free: a) 28% for the 300/300 group, b) 29% for the 300/100 group, and c) only 2% for Placebo.

Buprenorphine injection participants reported improvements beyond opioid use

Also in the Haight study, based only on individuals who completed the study, buprenorphine injection was associated descriptively (i.e., no statistical tests were conducted) with increased employment as well. Specifically, the buprenorphine 300/300 group increased from 40% employed at baseline to 51% at the end of the study, and the buprenorphine 300/100 group increased from 34% to 44%. The Placebo group, on the other hand, had decreased employment from 46% to 33%.

Non-opioid drug use descriptively decreased in buprenorphine injection groups during the study period, as well, though it remained common, particularly for cocaine (25-40%) and marijuana (30-40%).

Buprenorphine injections lead to similar reductions in opioid use compared to daily Suboxone

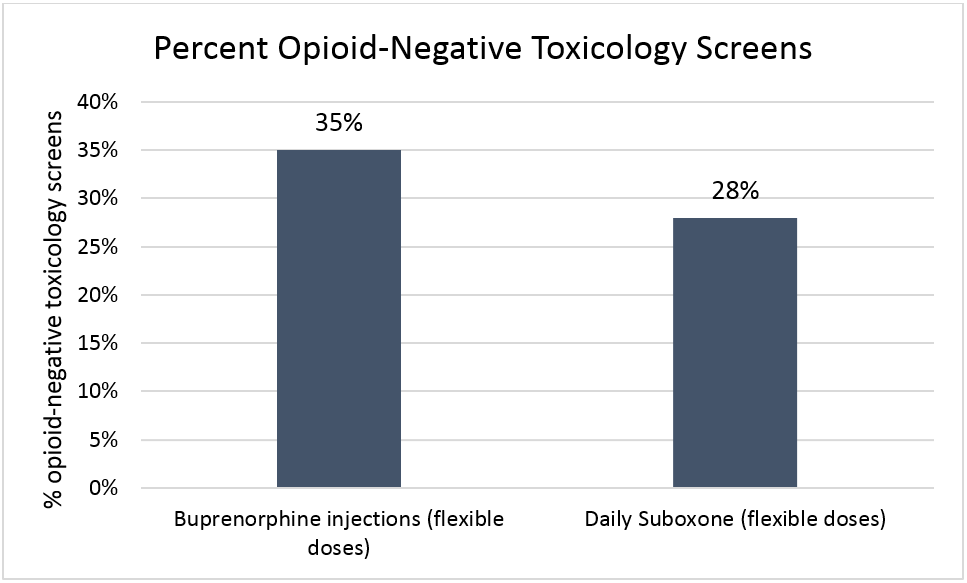

In the Lofwall study as illustrated in the figure below, buprenorphine injections at flexible doses did as well as daily Suboxone at flexible doses (i.e., groups were statistically similar on opioid-free drug screens).

Figure 2.

Also, 17% of the buprenorphine injection group were “responders” (see “How was this study conducted” for definition), similar to 14% in the Suboxone group.

Adverse buprenorphine injection events were relatively rare

In both Haight and Lofwall studies, adverse events leading to buprenorphine injection discontinuation were rare. Of note, however, is that 5-10% had itching or pain around the injection site.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

These two studies were rigorous tests of buprenorphine injections, comparing these novel formulations either to placebo injections, or pairing it with a placebo sublingual tablets and comparing it to daily Suboxone and placebo injection. In both studies, participants received individual drug counseling, shown to be helpful for individuals with cocaine use disorder in prior work. Taken together, these studies found buprenorhpine injection is better than placebo injection and a viable alternative to Suboxone. This additional way to access opioid use disorder medication may help address concerns with adherence, misuse/diversion, or opioid flow into communities. In a survey of individuals entering opioid use disorder treatment reviewed in a prior RRI bulletin, for example, one-third of those with Suboxone prescriptions misused their medication. Also, while most who used diverted (i.e., non-prescribed) Suboxone did so for therapeutic reasons, like staving off withdrawal, half also did so “to get high or alter their mood”. Buprenorphine injections, administered in health care settings, would help address such concerns.

The Haight study also sheds light on the contribution of psychosocial treatment to medication effects. Specifically, the medication placebo effects and individual drug counseling, in combination, accounted for one-eighth of the benefits provided by buprenorphine injections and counseling. In other words, the vast majority of benefit on opioid use individuals receive from this opioid use disorder intervention is accounted for by the medication itself. “Individual drug counseling”, which outperformed cognitive therapy and supportive-expressive therapy (a psychodynamic/psychoanalytic approach), in the treatment of cocaine use disorder, however, was designed as a twice-weekly psychosocial intervention, but was delivered only once a week or once a month in these studies. It is possible that treatment effects could be enhanced with greater fidelity to this more intensive version of individual drug counseling.

While not possible to directly compare the Haight and Lofwall studies due to different study methods (e.g., fixed vs. flexible buprenorphine injection doses) and slightly different outcomes, findings were broadly similar. Individuals receiving buprenorphine injections and individual drug counseling weekly can be expected to be abstinent from illicit opioids about 40% of the time. This 40% estimate is a conservative one, as it assumes that all missed drug tests would be positive for opioids.

Finally, overdose was rare in both studies. In the Haight study, there was only one overdose in the placebo group and in Lofwall study there were five overdoses in the Suboxone group and none in the buprenorphine injection group.

One downside is that buprenorphine injections are much more expensive than Suboxone at approximately $1700 per injection. If medically necessary, insurance may cover this cost (also see here). Given the existing issues with authorization of Suboxone from insurance companies, though, the relationship between insurance company policies and practices related to buprenorphine injection reimbursement and its real-world outcomes should be closely monitored, as it will almost certainly affect its public health impact.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Both studies were conducted in outpatient settings. These results may not be applicable to inpatient and residential settings.

- For the most part, studies did not test outcomes beyond abstinence. Buprenorphine injections may be associated with improvements in employment, though this finding should be replicated in other studies of buprenorphine injection and other buprenorphine–derived medications like Suboxone.

- While the Haight study of fixed buprenorphine injection doses showed 25-40% were using non-opioid drugs like cocaine and cannabis, the Lofwall study of flexible buprenorphine injection doses did not report other drug outcomes.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: These studies showed that a monthly (or weekly) buprenorphine injection leads to better opioid use outcomes compared to placebo injections and it does as well as Suboxone, the most commonly prescribed formulation of buprenorphine. Buprenorphine injections may be a viable alternative to Suboxone, addressing concerns about the need to take it every day, and potential misuse. It is more expensive, however. You may wish to discuss with your physician and insurance company as soon as possible if you want to learn more, to find out whether your insurance covers this novel injection formulation of buprenorphine, a well-established opioid use disorder medication.

- For scientists: These studies showed that a monthly (or weekly) buprenorphine injection leads to better opioid use outcomes compared to placebo injections and it does as well as Suboxone, the most commonly prescribed formulation of buprenorphine. Studies were rigorous with the study design accounting for potential contributions of positive medication expectancies via placebo control. Also of note is that for the study comparing buprenorphine injections to placebo injections, it helped disaggregate medication effects from the effects of additional “counseling” in the form of weekly check-ins, problem solving, and advice to participate in community-based recovery support services like 12-step mutual-help organizations. Future studies may adopt such an approach to help inform practitioners who prescribe Suboxone without any additional psychosocial support. Future studies may also test whether greater buprenorphine injection uptake is associated with lower levels of buprenorphine misuse and diversion.

- For policy makers: These studies showed that a monthly (or weekly) buprenorphine injection leads to better opioid use outcomes compared to placebo injections and it does as well as Suboxone, the most commonly prescribed formulation of buprenorphine. Given existing difficulties with authorization for Suboxone prescriptions, pre-emptive work with third-party payers, treatment providers, and patients may help maximize the public health benefits of this novel injection formulation of buprenorphine.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: These studies showed that a monthly (or weekly) buprenorphine injection leads to better opioid use outcomes compared to placebo injections and it does as well as Suboxone, the most commonly prescribed formulation of buprenorphine. Buprenorphine injections may be a viable alternative to Suboxone, addressing concerns about the need to take it every day and potential misuse. It is more expensive, however. You may wish to encourage patients to discuss with their insurance companies as soon as possible if they want to learn more, to find out whether they might cover the cost of this novel injection formulation of buprenorphine, a well-established opioid use disorder medication.

CITATIONS

Haight, B. R., Learned, S. M., Laffont, C. M., Fudala, P. J., Zhao, Y., Garofalo, A. S.,… Heidbreder, C. (2019). Efficacy and safety of a monthly buprenorphine depot injection for opioid use disorder: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32259-1

Lofwall, M. R., Walsh, S. L., Nunes, E. V., Bailey, G. L., Sigmon, S. C., Kampman, K. M.,… Kim, S. (2018). Weekly and Monthly Subcutaneous Buprenorphine Depot Formulations vs Daily Sublingual Buprenorphine With Naloxone for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med, 178(6), 764-773. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1052