In young adult heavy drinkers, does naltrexone work better for those drinking for reward compared with those drinking to cope?

Young adulthood is a time of increased experimentation and heavy use of alcohol and onset of alcohol use disorder. Treatments that help to reduce risky drinking are a necessity for this age group. Detecting for whom these interventions may or may not work best can improve tailoring of treatments to specific patient subgroups. This study examined whether the use of the medication naltrexone, an opioid antagonist that works by blocking the rewarding effects of alcohol, might reduce heavy drinking in young adults, and which types of drinkers benefit most.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

As adolescents develop into young adults, there are increasing opportunities for them to experiment with legal substances, such as alcohol, and more venues and social expectations for them to do so. Heavy use of alcohol during this developmental phase is associated with great public health burden in related consequences and costs to society: it can result in chronic health issues, violence, unemployment, and relational problems to name a few. Interventions and treatments that help to prevent or reduce risky drinking are a necessity for this age group and existing solutions typically generate only small reductions in alcohol consumption. Additionally, understanding for whom these interventions may work can help with identifying target populations and better use of resources as specific approaches may be tailored to them and thus be more effective. That is, although individuals may have many reasons for engaging in drinking, it has been proposed that there are several drinking phenotypes, characterized in part by different motivations for drinking: (1) primarily reward motivated drinking, where individuals drink to enhance pleasant feelings (e.g., excitement) and (2) primarily coping motivated drinking, where individuals drink to get relief from unpleasant feelings (e.g., stress or anxiety).

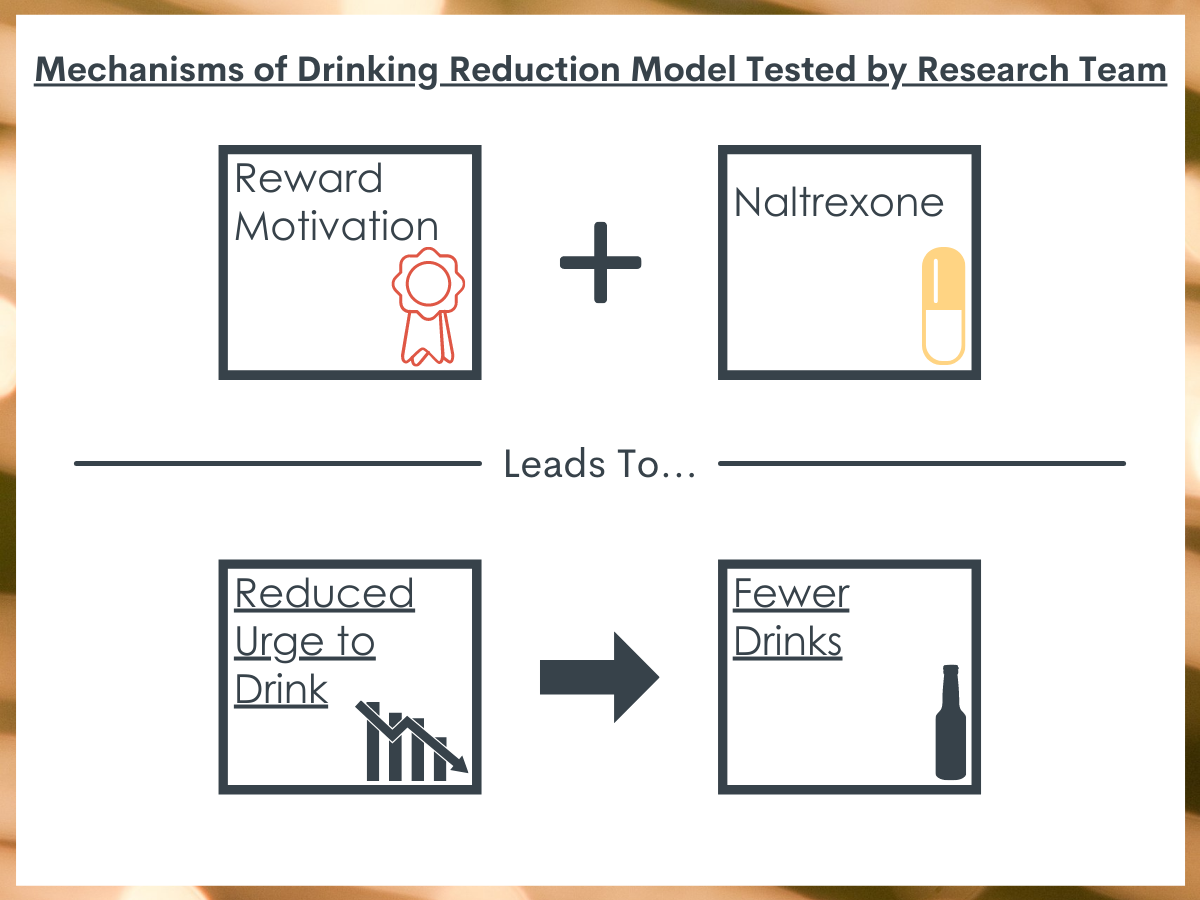

Naltrexone, an opioid receptor antagonist, produces small, but reliable reductions in drinking. It can be taken daily with booster doses before a drinking episode. Naltrexone works by blocking the positive reinforcement (“rewards”) of alcohol use, and so might be effective in reducing heavy drinking or preventing drinking altogether. As the proposed mechanism of naltrexone is that it reduces the perceived rewards of alcohol use, individuals who are motivated to drink to enhance reward might benefit most from its use, if they are also motivated to try naltrexone to reduce their drinking. In this study, the research team examined whether naltrexone was effective in reducing heavy drinking, and if so, whether those individuals who are motivated to drink for reward-based reasons might be most influenced by this type of intervention. In doing so, they were seeking to better understand mechanisms of this treatment so that it could be used more effectively with some individuals and to identify characteristics of individuals for which this treatment would be less effective.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The researchers in this study conducted secondary analyses of data from a randomized controlled trial that enrolled 128 young adults (ages 18–25) who engaged in heavy drinking. Heavy drinking was defined as 4 drinks in a day for women and 5 drinks in a day for men. In the study, the participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups: (1) a brief intervention and naltrexone or (2) a brief intervention and a placebo pill. The brief intervention used was the Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention of College Students (BASICS) intervention, modified to address medication management of drinking. Participants in the naltrexone group received a 25 mg daily dose and a 25 mg targeted dose on drinking days, which was to be taken at least 2 hours before anticipated drinking.

Participants in the study were enrolled for 8 weeks and completed daily surveys. The surveys collected data on how the participants were feeling (i.e., positive versus negative affect), drinking urges, drinking behavior, and social situations. The participants also completed a survey that assessed their motivation style of drinking: whether their motivation for drinking was reward (enhancement) or relief (coping) based. That is, someone who is considered a “reward drinker” is characterized by alcohol use that is primarily driven by the positive, rewarding effects of alcohol, while someone who is considered a “relief drinker” is characterized by alcohol use that is primarily driven by the distress-relieving effects of alcohol. The study team used the results to categorize participants into three groups based on their drinking motivation style: (1) high reward, (2) low reward, and (3) high reward/high relief. These three groups were used in the first set of analyses to examine whether the motivation for drinking influenced the effectiveness of naltrexone in reducing alcohol use. In this analysis, the study team included several control variables (sex, family history of alcohol use disorder, baseline alcohol abstinence, and smoking status).

Following this analysis, the authors tested several models to better examine mechanisms of change by drinking motivation style and treatment group. In the first model, the study team tested whether (1) drinking motivation style and treatment group influenced urges to drink and in turn, if (2) the changes in urges to drink were driving changes in alcohol use across the entire study.

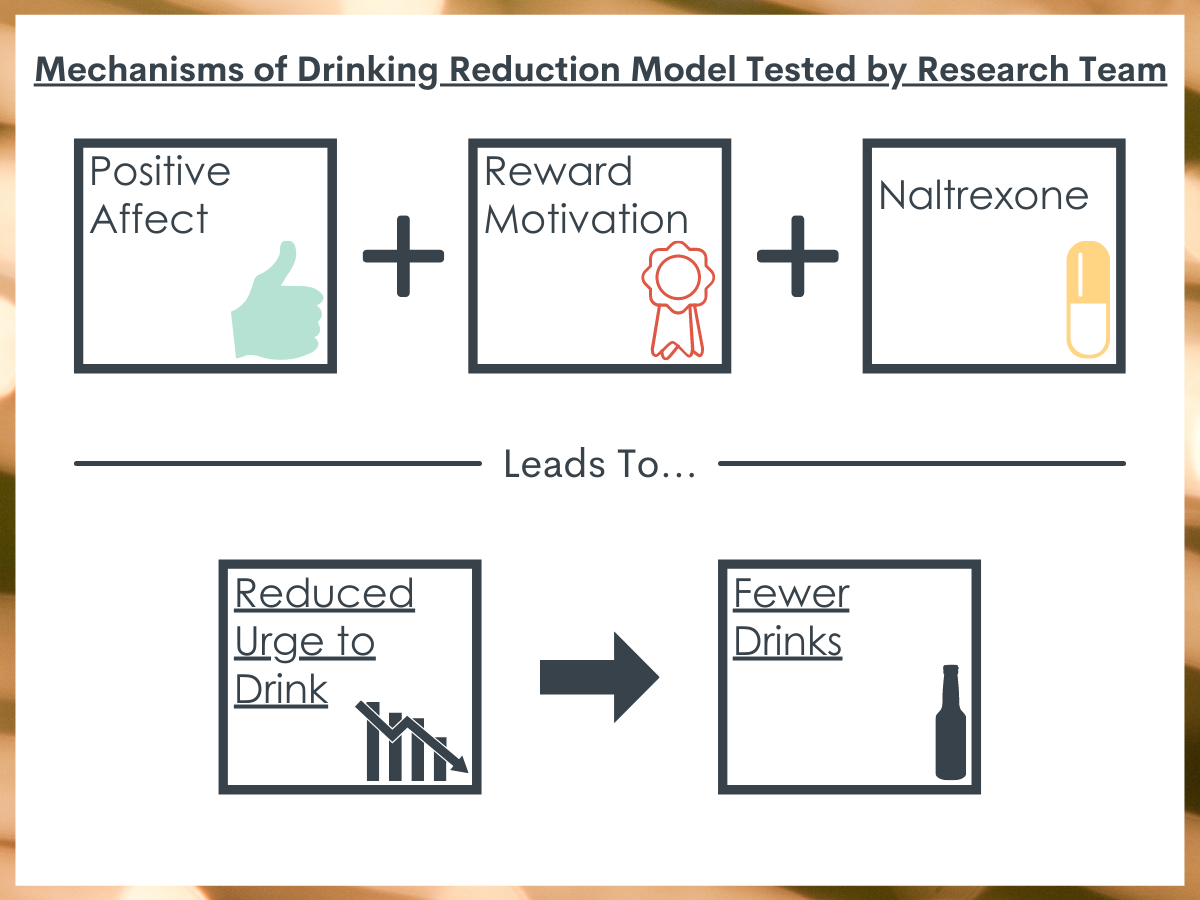

In the second model, the study team tested whether (1) same-day positive feelings (affect), drinking motivation style and treatment group influenced urges to drink and in turn, if (2) the changes in urges to drink were driving changes in alcohol use on days the participants reported drinking. The third model was identical to the second model, but examined alcohol use only on the days where participants were in social situations where alcohol was being consumed.

This sample of 128 young adults who engaged in heavy drinking were mostly male (69%), in college (71%), and white (77%). There was a large number with a family history of alcohol use disorder (38%), a risk factor for heavy drinking.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

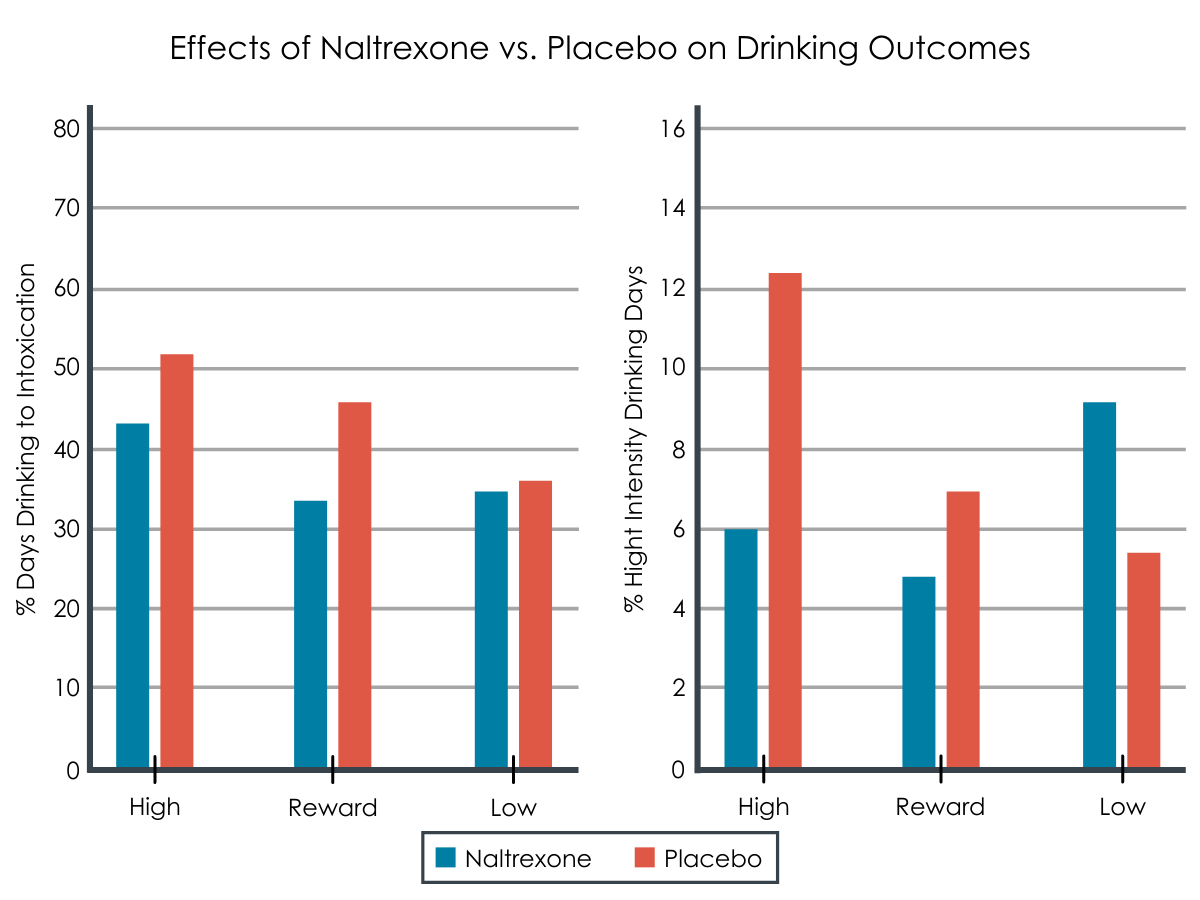

Naltrexone reduced some drinking outcomes by type of drinking motivation.

Among participants who were considered motivated to drink in the high reward style category (hereafter high reward group), they reduced the percent of days they drank to intoxication if they were in the naltrexone group, but not the placebo group. Among participants who were considered motivated to drink in either the high reward group or a group motivated both by high reward and high relief (hereafter high reward/high relief group), those in the naltrexone group but not in the placebo group, reduced the percent of days where they drank 8 drinks (women) or 10 (men) drinks on those days (i.e., high intensity drinking days). Drinking motivation type did not influence the naltrexone treatment effect for other measured alcohol outcomes including percent days abstinent, percent days heavy drinking, the number of drinks per drinking day, or their estimated blood alcohol concentration.

Mechanisms of treatment change varied by when the outcome was measured.

In this analysis, the study team examined whether or not the outcomes as a result of one’s motivation for drinking and treatment condition were changed by the (a) level of daily urges to drink and/or (b) daily reported positive feelings.

When the study team examined outcomes across all the treatment days in the study, the hypothesized pathway of naltrexone reducing daily urges to drink and subsequently reducing overall drinking was not supported.

When the study team examined outcomes across only the drinking days in the study, the hypothesized pathway of motivation style and naltrexone condition predicted positive affect, which, in turn, increased daily urge to drink, which then predicted overall drinking. Yet, this pathway was similar for each of the drinking motivation groups.

Finally, when the study team examined outcomes on only the days participants were exposed to a drinking situation (e.g., at a bar with friends), within the high reward group only (80 participants), naltrexone buffered against the effect of positive affect on urges to drink which, in turn, predicted number of drinks (i.e., the interaction of the drinking motivation category by treatment condition predicted the relationship between positive affect and urge to drink). Thus, naltrexone reduced one’s urge to drink only among the high reward group presumably by potentially interrupting the connection between affect and urges to drink, but only on the days in which they had both positive affect and were exposed to a drinking situation.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

In this study of 128 emerging adults, the research team found some evidence that naltrexone may work better in reducing certain types of heavy alcohol consumption among individuals with a reward style motivation for drinking on days when they had positive affect and were exposed to a drinking situation. That is, in line with other research, naltrexone may be most effective in reducing risky drinking among young adults who are motivated by the perceived reward of drinking, but not among those who may be drinking to cope, or as a way to deal with stressors. The research team found that one mechanism by which naltrexone could work among these reward style drinkers is that naltrexone reduces urges and drinking on days when participants had both higher positive affect and were exposed to a drinking event, such as by being out at a bar with friends.

Understanding reasons and motivations for drinking may be key when deciding on an intervention among groups of people in a similar environment or for a treatment plan when working with individuals. Despite the importance of individual characteristics leading to changes in drinking behaviors, the study also highlights the importance of the environment in the context of drinking, particularly heavy drinking: some attention to reducing opportunities for or preventing attendance at higher drinking risk events may be necessary, especially for settings where young adults are likely to meet and congregate (e.g., in college or at the workplace). Alternatively, working with young adults to practice and use strategies to reduce drinking when in these settings – called harm reduction – may also be an effective behavioral approach.

Another factor that is important to understand is that the use of naltrexone is effective only if used consistently and over a certain period of time for reducing heavy drinking: because it works by disrupting the drinking-reward pathway for some individuals, the association between taking naltrexone and reducing drinking rewards is a learned one. If individuals simply stop taking the naltrexone or if they continue to drink despite not feeling rewarded by the drinking, their bodies may not learn the association and their drinking may become more excessive. This attempt to push through the effects would greatly reduce naltrexone’s use as a prevention or treatment tool. Thus, individuals may need to be motivated to reduce their drinking before engaging in this form of treatment. Finally, given that these medication effects were only found for those with a reward-motivated drinking style, additional research on addressing those with a coping-motivated drinking style, in particular, to see whether other medications may be used to disrupt their pathway to heavy drinking is necessary. Alternatively, it may be that other types of psychosocial interventions may be a better fit for some young people, particularly those with coping motivated alcohol and other drug use disorders who are more severe clinical cases.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Although both groups received the brief intervention BASICS, it is unknown how the brief intervention may have impacted the findings, especially as there is evidence it is effective on its own. Given that there were different mechanisms of naltrexone treatment, it seems possible that there are alternative mechanisms of the brief intervention, such as protective behavioral strategies, which interacted with these drinking motivation, affect, or situational characteristics to affect the heavy drinking outcomes.

- This was a secondary data analysis that used multiple statistical tests without correction for these multiple comparisons; some of the models also had small sample sizes for the analysis. As a result, some of the findings could be a result of chance. Future research should be designed to empirically examine these relationships.

- This study did not examine other individual-level characteristics that are also strong predictors, such as motivation and self-confidence to stop or reduce drinking.

BOTTOM LINE

The researchers of this study of 128 young adults with heavy drinking behaviors found that the medication naltrexone appeared to help reduce heavy drinking, especially for those with a reward style of drinking and on days when participants felt good and were exposed to a drinking situation. The research team found that the reduction was most likely due to the proposed pathway of naltrexone reducing one’s urge to drink, which then reduced the amount of alcohol they consumed.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The use of medication to reduce heavy drinking and its related consequences may be a useful tool, especially among individuals who wish to reduce their drinking behaviors and for those who report drinking to have more fun (versus those who are drinking to find relief or to cope). This medication approach could be used with counseling to better support an individual in reducing or stopping their drinking. If you know someone who wishes to reduce their drinking, suggesting activities to have fun without drinking and in settings where alcohol may not be present, may also help them towards achieving this goal.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Individuals with heavy drinking who wish to stop may not know about, but could potentially benefit from, the use of naltrexone or even other evidence-based medications that research has shown are effective although these have been approved for more severe alcohol use disorder cases. Reducing the culture of, or opportunities for, heavy alcohol use, or linking young adults to programs for environments which support fun without alcohol consumption, such as collegiate recovery programs may also better support young adults in alcohol-heavy contexts. As well, linking individuals to in-the-moment environment support for drinking situations could be an effective form of intervention.

- For scientists: Despite the support found for the hypothesized pathway of the use of naltrexone to reduce drinking urges and thereby drinking among reward-style drinkers, there are several areas which require further investigation. First, the combination of an intervention with the medication may have created further nuance in pathways to reduce drinking, a relationship which should be examined. As well, given that the relationship was strongest on days with positive affect and exposure to drinking, the findings suggest that further research using ambulatory monitoring or environmentally-prompted messages may be useful for a heavy-drinking population, as these methods have been studied in smoking cessation research. Better understanding mechanisms for those with a coping-style of drinking is also necessary. Finally, there is still much research to be done on the way different medications may work to affect heavy drinking by drinking style profile. For example, other work has found that while naltrexone was better for reward than relief drinkers, another medication, acamprosate, contrary to hypotheses, was no better for relief vs. reward drinkers among adults with an alcohol use disorder; yet, this may have been due to the high level of existing drinking among study participants.

- For policy makers: Stricter alcohol policies targeted to reduce binge drinking may help to reduce heavy drinking and related consequences among young adults. Dedicated healthcare funding to support the use of medication as a treatment approach or for research which can better address how to reach individuals when in a drinking environment may also drive reductions in heavy drinking among young adults.

CITATIONS

Roos, C. R., Bold, K. W., Witkiewitz, K., Leeman, R. F., DeMartini, K. S., Fucito, L. M., Corbin, W. R., Mann, K., Kranzler, H. R., & O’Malley, S. S. (2021). Reward drinking and naltrexone treatment response among young adult heavy drinkers. Addiction, 116(9), 2360-2371. doi:10.1111/add.15453