“Natural recovery” from alcohol use disorder: What characteristics predict successful low-risk drinking one year later?

Many individuals achieve alcohol abstinence or low-risk alcohol use (commonly referred to as moderation) without any treatment whatsoever – a process known as ‘natural recovery’. However, little is known about who is most likely to succeed without treatment. This study sought to address this critical knowledge gap in order to get a better sense of who is likely to succeed in achieving their drinking goals outside of the context of formal treatment.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Decades of research has sought to identify individual factors that predict the likelihood an individual will respond to alcohol use disorder treatment. However, this research has largely focused on people with greater alcohol use disorder severity engaging in formal, intensive, abstinence-based treatment approaches. Many individuals, though – especially those with milder forms of alcohol use disorder – may eventually moderate or stop alcohol use on their own (commonly referred to as ‘natural recovery’), or through less intensive, brief interventions and population-based public health interventions.

Little is known, however, about the kind of individual factors that may predict whether someone is likely to be successful moderating or stopping alcohol outside of the context of established treatment approaches. Further, it is not known if drinking behaviors before a natural recovery attempt can help indicate the likelihood of low-risk alcohol use or abstinence success. These pre-recovery markers of likelihood of sustained recovery versus return to problem drinking may help individuals and any family members supporting them to decide which recovery pathway to try first (abstinence vs. low-risk drinking). To address this knowledge gap, the authors of this study investigated whether different profiles of alcohol and well-being, based on pre-recovery characteristics, might predict whether someone is likely to successfully drink at low-risk levels or achieve abstinence without the use of formal treatment or mutual-help programs like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a retrospective analysis of data from five observational studies conducted between 1993 and 2015 that monitored a total of 616 individuals seeking to address their drinking problem outside the confines of traditional treatment and mutual-help programs through ‘natural recovery’. Participants were individuals who had “overcome a drinking problem” without formal treatment, between three weeks and six months earlier, defined by abstinence or NIAAA low-risk drinking, no drinking consequences, and no alcohol dependence symptoms. All participants were assessed at baseline, and then again 12 months later. A timeline follow-back interview conducted at baseline and follow-up assessed drinking practices, income, and expenditures covering the preceding year, which generated detailed behavioral records covering the two years surrounding participants’ drinking resolution date.

Eligibility criteria in all studies included, 1) ≥ 21 years of age, 2) ≥ 2 years problem drinking history (Mean= 16.6 years problem drinking), 3) no current other drug misuse (except nicotine), and 4) recent cessation of high-risk drinking while residing in the community (Mean = 14.5 weeks).

The authors used a statistical technique that creates profiles of individuals based on pre-resolution drinking behaviors, degree of alcohol dependence, number of alcohol-related problems, and the perceived reward value of drinking. They then investigated whether the profile participants belonged to was associated with their drinking outcome during the one year follow up; i.e., non-abstinent recovery, abstinent recovery, or unresolved (not in recovery).

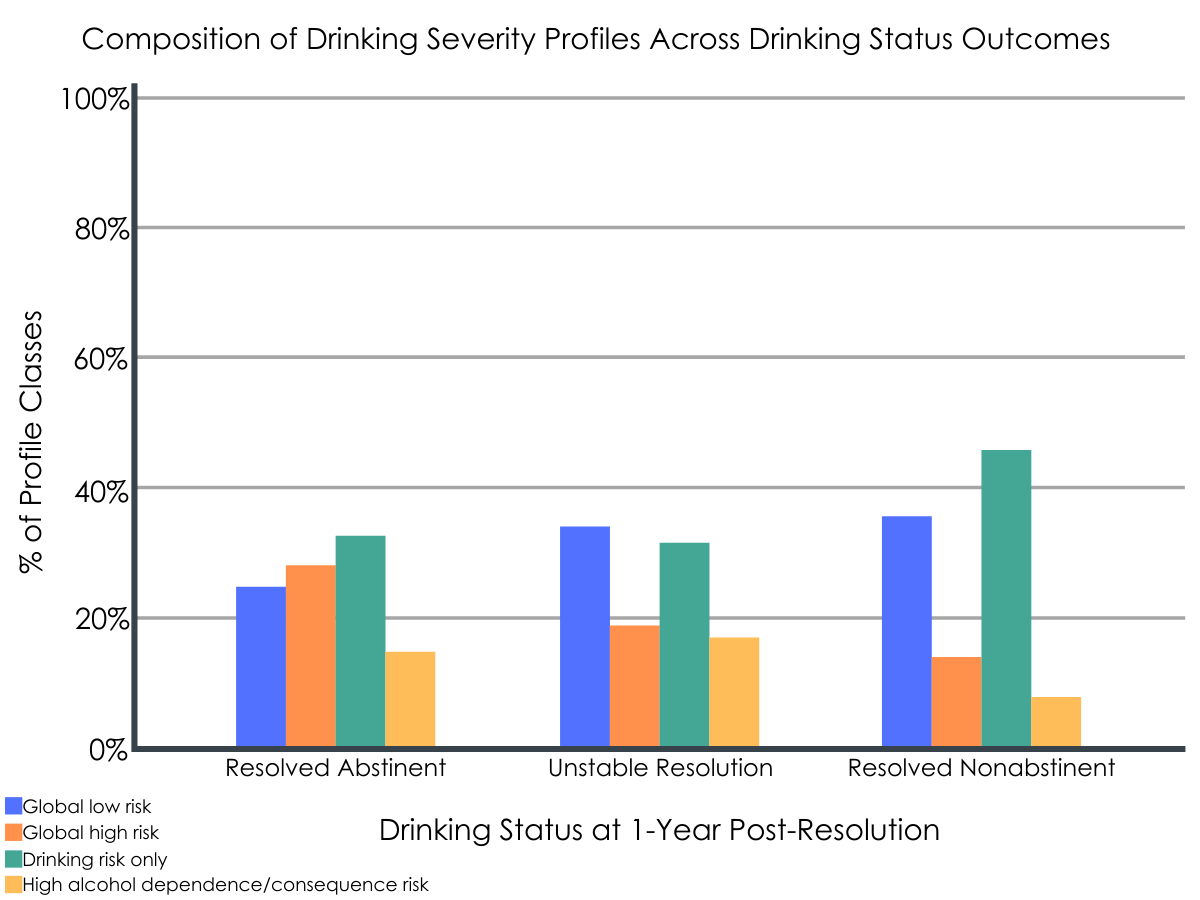

The authors identified four profiles based on these pre-resolution characteristics: 1) Global low risk across all severity indicators, 2) Global high risk across all severity indicators, 3) drinking risk only, characterized by low dependence severity and low alcohol problems with frequent heavy drinking, and 4) high dependence and high alcohol problems with infrequent heavy drinking.

Drinking outcomes based on the entire one-year follow-up were: 1) Resolved abstinent, i.e., continuously abstinent (n = 273), 2) resolved non-abstinent, i.e., drinking within low-risk guidelines (i.e., lower risk drinking only, no relapses or alcohol-related problems; n = 80), or 3) unstable resolution, i.e., one or more relapses to alcohol use disorder defined as any daily drinking in excess of NIAAA heavy drinking thresholds [4+ / 5+ drinks in one day for women / men], (n = 140).

Four major factors were considered regarding individual alcohol risk profiles (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Most participants had not received formal treatment or attended mutual help groups like AA (69.0%); 17.6% had attended AA only, and 13.5% had attended alcohol treatment plus AA at some point before their recent alcohol quit attempt. Although not required for study participation, almost everyone (99.4%) met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) threshold for alcohol dependence meeting three or more of the seven dependence criteria.

On average, participants were middle-aged, middle-income, and educated beyond high school. The gender composition was 67% male, and the race/ethnicity composition was representative of the southeast U.S. region where the research was done (65% White; 32% African American; <1.2% each Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, or other race/ethnicity). The drinking status at 1-year follow-up of 123 participants was unknown because they either withdrew early (n= 20), died (n= 5), or did not keep follow-up appointments (n= 98). Participants lost from the study (20% of the enrolled sample of 616) were similar to the rest of the sample in terms of problem severity and help-seeking history.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Men and women in the resolved non-abstinent group consumed on average about 2.25 and 1.98 standard drinks per drinking day, respectively, whereas men and women in the unstable resolution group consumed on average about 6.66 and 5.91 standard drinks per drinking day, respectively.

Compared to participants who maintained low-risk alcohol use over follow-up (resolved non-abstinent), participants who were continuously abstinent (resolved abstinent) were approximately three times more likely to belong to the global high risk profile than the global low risk profile. Also, they were 65% less likely to belong to the “drinking risk only” profile than the global high-risk profile.

Further, compared to participants who drank within low-risk guidelines (resolved non-abstinent), abstinent participants (resolved abstinent) were 4.5 times more likely to belong to the high dependence and high alcohol problems with infrequent heavy drinking risk profile, than the global low risk profile. Also, those who did not resolve their problem were 4.6 times more likely to belong to the high dependence and high alcohol problems with infrequent heavy risk profile, than the drinking risk only profile.

Figure 2. Results from the study, indicating drinking severity profiles and the percentage of individuals within each profile based on 1-year outcomes and drinking risk.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Findings from this study suggest that successful low-risk drinking during the post-resolution year is most likely among individuals with lower alcohol dependence, fewer functional problems related to drinking, and less money spent on alcohol versus money saved prior to resolving their problem. Those with global low risk were about three times more likely to be moderately drinking over follow-up versus abstinent compared to those with global high risk. It is possible that those with global high risk had been unsuccessful in their attempts to moderate and ultimately decided to pursue a goal of abstinence.

Importantly, heavier alcohol use in and of itself does not necessarily predict less success moderating alcohol use. For instance, participants who were frequent heavy drinkers at baseline, but had low dependence severity and low alcohol related problems were most likely to be low-risk drinkers over follow-up. Further, those who drank heavily but with few consequences were 4.6 times more likely than those with high dependence and high alcohol problems with infrequent heavy drinking to have moderated their drinking, versus experiencing unstable resolution characterized binge drinking and one or more relapses to alcohol use disorder.

Taken together, these results suggest that it’s not drinking quantity that best predicts likelihood of being able to drink within low risk guidelines, but rather alcohol dependence severity and having a history of drinking problems and consequences. In other words, for individuals with greater alcohol dependence and histories of drinking problems and consequences, trying to engage in low-risk drinking is likely a risky proposition.

These findings should however be considered in light of several of significant methodological issues in this study. First, participants’ drinking goals at baseline did not appear to be factored into the analyses. This would appear to be an important factor to consider given the major influence individuals’ drinking goals have on drinking outcomes. Second, participants who dropped out of the study were not accounted for in the final analysis. Though there is no way to know for sure what happened to these participants, a prudent approach might have been to consider these individuals as unstable resolvers characterized by binge drinking and one or more relapses to alcohol use disorder given these participants had similar alcohol problem severity to other groups at baseline. Third, given the authors’ focus on predicting natural recovery success, they required an outcome distribution at follow-up with many stable abstinent or low-risk drinking recoveries. Thus, because of generally high relapse rates among individuals in early alcohol use disorder recovery, the studies included in this analysis deliberately oversampled individuals with some initial success in abstaining or drinking moderately, to ensure they would have enough individuals in stable recovery to analyze. As such, it cannot be known if their findings would be the same with a sample more akin the actual population of individuals with drinking problems. Along these lines, previous work has shown that among individuals with alcohol dependence, over three-year follow-up, those who are abstinent from alcohol are more likely to be free from alcohol use disorder symptoms compared to those engaged in NIAAA defined low-risk drinking (no more than three drinks on any single day and no more than seven drinks per week for women, and no more than four drinks on any single day and no more than 14 drinks per week for men) and high risk drinking (4+ / 5+ drinks in one day for women / men).

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Though participants’ alcohol use goal was assessed at baseline (low-risk drinking or abstinence), this was not considered in subsequent analyses.

- Participants who were lost to the study were not considered in the final analyses, which may have led to under-representation of the unstable resolvers characterized by binge drinking and one or more relapses to alcohol use disorder.

- Though it made sense from a research methods perspective, individuals with some initial success in abstaining or drinking moderately were oversampled in the parent studies used in this analysis limiting generalizability of these findings.

- A single quantity-frequency measure of drinking practices was examined (heavy drinking days).

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Findings from this study suggest that successful low-risk drinking is most likely among individuals with lower alcohol dependence, fewer functional problems related to drinking, and who spend less money on alcohol compared to other things. Additionally, results suggest that heavier alcohol use in and of itself does not necessarily predict less success moderating alcohol use. Participants who were frequent heavy drinkers at baseline but had low dependence severity and low alcohol related problems were also able to drink within low-risk guidelines. Taken together, these findings highlight the need to consider not just the frequency of heavy drinking but multiple factors including severity of alcohol dependence and alcohol use problems in addition to alcohol use when deciding whether low-risk alcohol use or abstinence is the right path for an individual.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Findings from this study suggest that successful low-risk drinking is most likely among individuals with lower alcohol dependence, fewer functional problems related to drinking, and who spend less money on alcohol compared to other things. Additionally, results suggest that heavier alcohol use in and of itself does not necessarily predict less success moderating alcohol use, although individuals drinking large quantities of alcohol would likely have less success achieving low-risk drinking. Participants who were frequent heavy drinkers at baseline but had low dependence severity and low alcohol related problems also seemed to be able to moderate their drinking. Taken together, these findings bring to light the importance of using multidimensional severity indicators that encompass functional variables in addition to drinking practices to predict drinking outcomes among those attempting to change their alcohol use behaviors outside the confines of traditional addiction treatment programs.

- For scientists: Findings from this study suggest that successful low-risk drinking is most likely among individuals with lower alcohol dependence, fewer functional problems related to drinking, and who spend less money on alcohol compared to other things. Additionally, results suggest that heavier alcohol use in and of itself does not necessarily predict less success moderating alcohol use, although individuals drinking large quantities of alcohol would likely have less success achieving low-risk drinking. Participants who were frequent heavy drinkers at baseline but had low dependence severity and low alcohol related problems also seemed to be able to moderate their drinking. Taken together, these findings bring to light the importance of using multidimensional severity indicators that encompass functional variables in addition to drinking practices to predict drinking outcomes among those attempting to change their alcohol use behaviors outside the confines of traditional addiction treatment programs. Future research should investigate whether different temporal patterns of pre-resolution drinking frequency, quantity, and variability aid outcome prediction, and control for participant drinking goals.

- For policy makers: Findings from this study suggest that successful low-risk drinking is most likely among individuals with lower alcohol dependence, fewer functional problems related to drinking, and who spend less money on alcohol compared to other things. Additionally, results suggest that heavier alcohol use in and of itself does not necessarily predict less success moderating alcohol use, although individuals drinking large quantities of alcohol would likely have less success achieving low-risk drinking. Participants who were frequent heavy drinkers at baseline but had low dependence severity and low alcohol related problems also seemed to be able to moderate their drinking. There is increasing awareness in the addiction research community that there are multiple paths to recovery from substance use disorder, many including abstinence, but also some that include moderate alcohol use. It is imperative that policies support access to a range of treatment/recovery options. Additionally, rather than court-mandating all individuals with substance use problems to 12-step programs, the criminal justice system should consider other recovery approaches that may be more appropriate for individuals with less severe substance use problems. Finally, increased alcohol taxation has been shown to reduce alcohol use among individual with low and high alcohol use problem severity. As such, increasing alcohol taxes may have an indirect public health benefit.

CITATIONS

Tucker, J. A., Cheong, J., James, T. G., Jung, S., & Chandler, S. D. (2020). Preresolution drinking problem severity profiles associated with stable moderation outcomes of natural recovery attempts. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 44(3), 738-745. doi: 10.1111/acer.14287