What is recovery anyways? A proposed novel way of measuring ‘recovery’, informed by those in recovery and service providers

The term “recovery” is widely used by numerous stakeholders in the field of addiction, yet how exactly to define and measure it remains a topic of debate. In this study, scientists from King’s College in London, UK, created a novel recovery measure, and conducted several tests to see how it measured up.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The term “recovery” is widely used by numerous stakeholders in the field of addiction: those affected by substance use disorders, their loved ones, treatment providers, policy makers and scientists, to name just a few. It is a term that has grown out of the grassroots effort to focus more on healing and hope than purely on the elimination of disease (White, 2000). Yet how exactly to define recovery remains a topic of debate.

Ideally, a measure of recovery could be used as an outcome measure in clinical care and research (e.g., to track patient progress, to evaluate treatment programs). In order for such an outcome measure to be meaningful, however, it needs to resonate with multiple stakeholders: those who fund recovery services, those who provide services, and those who use services. In the interest of moving towards a shared language – if not shared goals – Dr. Joanne Neale and colleagues have conducted a series of studies to create a self-report questionnaire–the Substance Use Recovery Evaluators (SURE)–that captures recovery, based on rigorous feedback provided by those in recovery and service providers.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

A series of staged focus groups to generate and refine items, followed by two formal, large sample evaluation studies in the United Kingdom.

Twenty-five UK-based addiction treatment providers generated a list of indicators reflecting recovery. Forty-four current and former drug and alcohol treatment service users refined this list. Neale and colleagues transformed the list of indicators into items that can be used in a questionnaire, which were revised in two more focus groups with drug and alcohol treatment participants. The resulting questionnaire was further tested and refined in two more samples of drug and alcohol treatment participants (18 and 30 individuals, respectively). The resulting questionnaire was completed as part of a larger survey in two larger samples of current and former patients: a locally recruited and in-person participating sample of 461, recruited from community-based clinical services, third sector services (i.e., government funded non-profit organizations), and peer support services; and a sample of 114 individuals recruited from recovery-focused organizations based across England and Scotland, who completed the survey online.

- READ MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

Participants self-reported their demographics and recovery-relevant variables (i.e., last month substance use, and yes/no indices of being in recovery, being homeless, in paid legal work, in residential treatment, in prison, receiving addiction medication, engaged in mutual help) and also completed two widely-used, validated scales of quality of life and recovery capital.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The proposed questionnaire captured five dimensions that describe recovery: substance use, material resources, outlook on life, self-care and relationships. Psychometric analyses eliminated items that performed poorly, that is, had low test-retest stability (a measure of how reliable a test is across time), were only tangentially related to the five factors, or were related to multiple factors. After this sophisticated set of measurement analyses, these five factors were found to be best captured by a total of 21 of the original list of items. Importantly, the items functioned the same in women and men. The five factors correlated strongly with validated scales, with highest correlations when the content of the scales were matching (e.g., the correlation between the “psychological health” subscale of the existing quality of life scale and the SURE factor “self-care”, which are intuitively similar, was stronger than the correlation between the addiction recovery capital subscale “housing and safety” and the SURE factor “substance use”, which are less similar). As a further test of the validity of the proposed scale, Neale and colleagues tested if the scale’s total scores differed between groups of people who would be expected to differ in terms of their recovery progress. For example, they compared participants with paid legal work vs. those without. As would be expected, those with paid legal work scored higher on the proposed recovery questionnaire, further indicating validity of the proposed questionnaire.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study builds on prior efforts to define recovery. In 2006, a consensus panel consisting of researchers, treatment providers, recovery advocates, and policymakers defined recovery as “a voluntarily maintained lifestyle characterized by sobriety, personal health and citizenship” (Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel, 2006). Meanwhile, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) published its own definition of recovery, which entails a description of 10 guiding principles of recovery, namely, hope, person-driven, many pathways, holistic, peer support, relational, culture, addressing trauma, strengths/responsibilities and respect.

To simplify matters, RRI researchers proposed a bi-axial formulation, to highlight that there may simply be a reciprocal relationship between remission from a substance use disorder on the one hand, and recovery capital, encompassing health, housing, education/employment, social relations, enjoyment and purpose in life, on the other hand (Kelly & Hoeppner, 2014). None of these efforts, however, produced an actionable scale, which could be used as an outcome measure in clinical care and/or research.

Efforts to create actionable scales have produced rather complex and long measures. For example, in line with the biaxial formulation, the “Assessment of Recovery Capital” (ARC) scale focuses solely on recovery capital, and not on substance use directly (Groshkova & White, 2012). It is, however, rather long (50 items). A brief version exists, but focuses on less concrete and more experiential markers of recovery (e.g., does not assess having stable housing, but instead uses the item “My living space has helped to drive my recovery journey”) (Vilsaint et al., 2017).

Another, more recent effort, that is, an internet-based study of 9,341 individuals who self-identified as being in recovery, identified 35 items, describing four factors of recovery (Kaskutas et al., 2014).

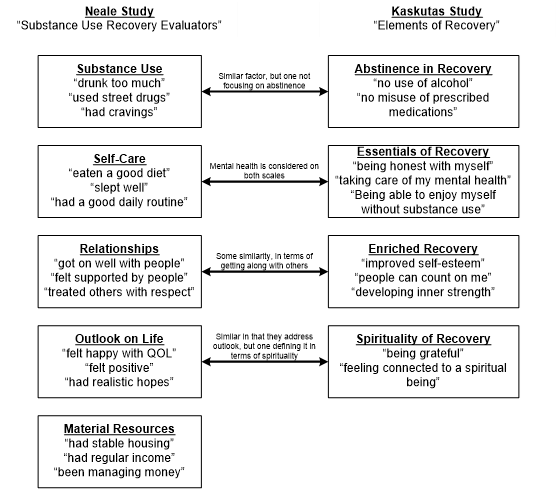

The proposed scale in the Neale study is shorter, and involved both service providers and service users in its development, using an iterative, rigorous, best-practice series of studies, resulting in a scale that resonates well with both of these two important stakeholder groups. Both the Kaskutas study and the Neale study consulted individuals who were in varying stages of their recovery, including those who did not consider themselves to be in recovery (16 percent in the Neale study), those who considered themselves ‘recovered’ (13 percent in the Kaskutas study), and many who had achieved a substantial number of years of recovery (23 percent Kaskutas study; unknown percentage but many “former service user” participants in the Neale study). Similar factors emerged in both studies (see Figure), but the factors defined in the Neale study are more general and less echoing traditional themes (e.g., lack of problematic substance use instead of abstinence, general self-care instead of honesty, feeling happy and positive instead of grateful and connected), and acknowledge that material resources contribute to recovery.

- LIMITATIONS

-

The proposed measure is based on the recovery experience of stakeholders in the UK (i.e., UK service providers, treatment participants, and addiction scientists), and thus it remains to be tested how well the generated items and scale translate to international settings with a different healthcare delivery system. The sample size, while considered generally adequate for scale validation purposes, was nevertheless relatively small in that it had relatively little diversity with regards to specific subpopulations (e.g., only 70 homeless participants). Only a subsample (111 individuals) completed the validated scales used to test if the proposed scale functioned similarly to related scales.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Recovery is complex and multi-faceted. This research highlights five factors that may be considered markers of recovery progress: substance use, material resources, outlook on life, self-care and relationships. Also note that the explicit goal of this research project was to create a patient-reported outcome measure, reflecting an increasing emphasis placed on incorporating patient views and perspectives in designing and evaluating systems of care.

- For scientists: While this scale is an excellent, valid, brief, easily administrable scale to capture an important clinical outcome, further work remains to be done, including, for example, research to (1) validate this scale in larger, more heterogenous populations and settings, (2) establish cut-off points for the interpretation of scores, and (3) examine how well this scale functions prospectively to track progress over time.

- For policy makers: This scale reflects the complexity inherent in defining recovery. The presence of five identified factors speaks to the multi-faceted nature of recovery, all of which are important contributors to the establishment of successful long-term recovery. The ambiguity reflected in the wording of some of the items reflect the diversity of individual life circumstances, where specific, narrowly defined markers were screened out in favor of more encompassing markers of recovery (e.g., “had a good daily routine” instead of “had a full-time job”). Note also the relatively understated emphasis on substance use (only 6 out of 21 items addressed substance use), which is in line with recent, more inclusive non-abstinence based approaches, and which also reflects that recovery embodies more than the cessation of substance use. As such, policies intended to enhance recovery outcomes among individuals with substance use disorder, and the funding need to support such policies, would ideally target multiple domains of functioning.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: The proposed scale is brief (i.e., 21 items), worded in easily understandable English, and addresses multiple components of recovery. As such, it is readily usable and captures recovery progress markers deemed relevant and impactful by a large variety of treatment providers and treatment participants.

CITATIONS

Neale, J., Vitoratou, S., Finch, E., Lennon, P., Mitcheson, L., Panebianco, D., . . . Marsden, J. (2016). Development and Validation of ‘Sure’: A Patient Reported Outcome Measure (Prom) for Recovery from Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend, 165, 159-167. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.006