Nurse practitioners play an important role in buprenorphine access

Most people with opioid use disorder do not receive treatment and even fewer receive evidence-based treatment with medications, such as buprenorphine. Uncovering factors associated with buprenorphine prescribing among providers can help identify health care policy targets to increase medication access. This study used Medicaid data from Virginia to examine factors associated with buprenorphine prescribing among eligible providers.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Medications for opioid use disorder, such as methadone or buprenorphine (commonly prescribed in formulation with naloxone and known by the brand name Suboxone), substantially decrease opioid use and opioid-related mortality. Buprenorphine is a medication that can be prescribed in an office-based setting by a qualified provider who until recently (April 2021) had to undergo additional training to obtain a “waiver”, also called an “X-License”. This more flexible, less restrictive, and more accessible approach is very different from methadone, where a patient must frequently visit (often daily) a highly structured specific outpatient Opioid Treatment Program.

Recent federal policy changes implemented in 2016 have expanded access to buprenorphine by increasing the number of patients a trained provider (i.e., providers that have an “X-license”) can treat and allowing nurse practitioners and physician assistants also to become trained in buprenorphine prescribing. Despite the strong evidence for methadone and buprenorphine, it is estimated that only 11% of individuals who met criteria for opioid use disorder in 2020 received these medications. While reasons for underutilization are complex, one partial explanation is a gap between treatment need and the ability of clinical providers and systems to provide it (treatment capacity).

Medicaid insured patients are disproportionately affected by opioid use disorder, representing 4 in 10 people with this chronic medical condition nationally. Despite this high prevalence, providers and programs are sometimes reluctant to accept Medicaid patients due to low reimbursement rates and high administrative burden (more paper work and phone calls). Therefore, a better understanding of who is treating Medicaid patients with opioid use disorder is important for efforts to expand access to buprenorphine for this vulnerable population. In this study, researchers used several data sources to examine Medicaid participation among all buprenorphine-waivered providers in Virginia in 2019.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study linked several administrative data sources to a list of Virginia providers authorized to prescribe buprenorphine in 2019 to examine factors associated with prescriptions for Medicaid patients. Primary study questions focused on prescribing differences between physicians and non-physicians (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) as well as provider characteristics and community characteristics that are associated with prescribing buprenorphine for Medicaid patients.

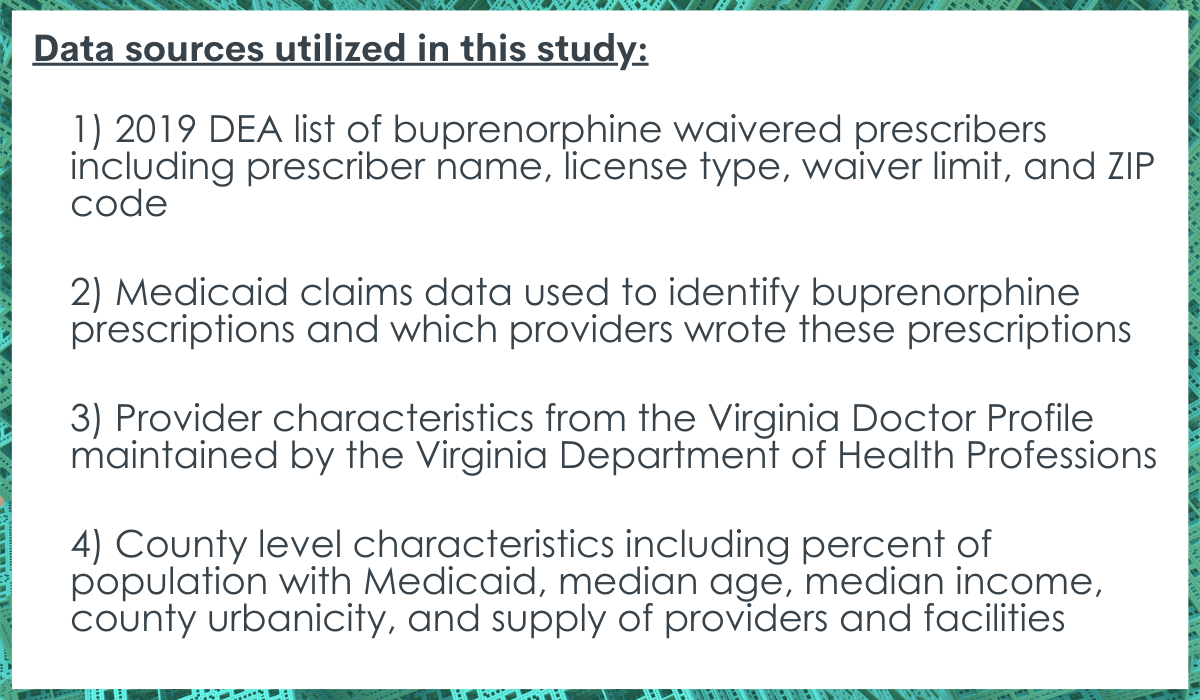

This study used several data sources. First, a list of Virginia providers authorized to prescribe buprenorphine was obtained through Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and included prescriber name, prescriber license type (physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant), waiver limit (30, 100, or 275 patients), and zip code. Second, Medicaid claims data was linked to the DEA data source to identify both buprenorphine prescriptions and which waivered providers wrote these prescriptions. Third, provider characteristics from the Virginia Doctor Profile maintained by the Virginia Department of Health Professions were linked to the DEA data source to identify practice specialty, years of practice, and self-reported acceptance of Medicaid patients among waivered providers. Fourth, county-level characteristics were linked to the practice location of waivered providers. These included percent of population with Medicaid, median age, median income per capita, urbanicity of the county, supply of providers, and whether the county had a specialty treatment facility that provided buprenorphine treatment. These data came from various sources including the American Community Survey, the Area Resource File, and the Behavioral Treatment Services Locator maintained by SAMHSA.

Researchers constructed measures of buprenorphine prescription utilization from 2019 Virginia Medicaid claims data. Both in-clinic buprenorphine administration and buprenorphine dispensing from a pharmacy were captured. Instances where buprenorphine was being used to treat pain were excluded so that findings reflected buprenorphine prescribing specifically for opioid use disorder.

Two provider measures were constructed: 1. Any Medicaid claim for a buprenorphine prescription in 2019 2. The number of unique Medicaid patients treated in 2019, which were then further defined as providers who were in the 75th percentile or higher in the number of Medicaid patients treated. The primary variable of interest was a three-category measure of license type (physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant).

The researchers examined what factors predicted prescribing buprenorphine for Medicaid patients. First, researchers examined factors that predicted trained providers prescribing buprenorphine to any Medicaid patient. Second, researchers examined factors that predicted treating a large number of Medicaid patients with buprenorphine (defined as in the 75th percentile or higher) among providers who treated any Medicaid patient with buprenorphine.

Out of nearly 26,000 nonsurgical physicians in Virginia, 855 had received the training needed and received the waiver to prescribe buprenorphine as of 2019. Out of the nearly 9000 nurse practitioners in Virginia, 242 had received the training, and of the nearly 3000 physician assistants, 36 had received the required training.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Only a small percentage of providers are buprenorphine prescribers in Virginia.

Only 3.3% of physicians, 3.8% of nurse practitioners, and 2.7% of physician assistants were eligible to prescribe buprenorphine. Among the 3.3% who were physicians, 40% of these were psychiatrists and 31% were primary care physicians, and physicians who self-reported accepting new Medicaid patients were somewhat more likely to be waivered (3.8% vs. 2.8%). Most providers (70%) were only eligible for the 30-patient limit and only 10% were in rural areas.

Nurse practitioners are more likely to prescribe buprenorphine to Medicaid patients.

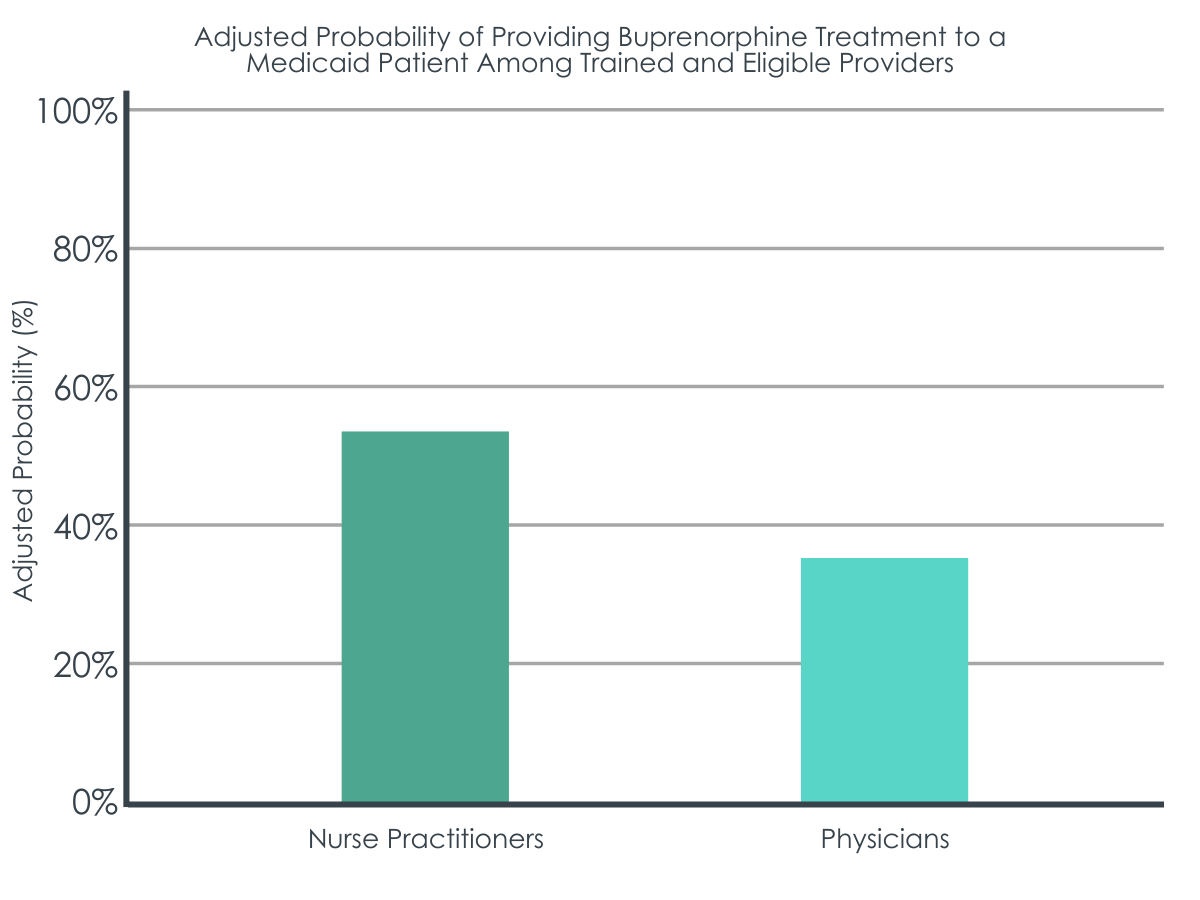

Two in five (42.8%) of the trained and eligible prescribers in Virginia actually provided buprenorphine treatment to a Medicaid patient in 2019. Newly eligible non-physicians (waivered for a year or less) were more likely to treat a Medicaid patient compared with newly trained and eligible physicians (41% vs. 27%). The odds of nurse practitioners treating any Medicaid patient with buprenorphine were two times the odds of physicians treating any Medicaid patient with no statistical differences between physicians and physician assistants. Adjusting for other factors, the probability of treating any Medicaid patient was 53% for nurse practitioners and 36% for physicians. Higher patient limits were also associated with much higher likelihood of Medicaid participation (100 patient-limit odds ratio = 6.7 and 275 patient-limit odds ratio = 29.4 compared with 30-patient limit). Other factors making providers more likely to prescribe were 1. Practicing in counties with a specialty treatment facility offering buprenorphine, 2. Practicing in counties with a larger overall supply of providers, and 3. Practicing in small metropolitan counties.

Nurse practitioners are also more likely to treat a large number of Medicaid patients.

Among eligible trained prescribers who treated any Medicaid patient, 10% treated only one patient while 25% treated three or fewer. About half of prescribers treated more than 10 Medicaid patients while 25% treated 39 or more patients (defined as the 75th percentile and “treating a large number of Medicaid patients” in this study).

Among eligible trained prescribers who treated any Medicaid patient, the odds of nurse practitioners treating a large number of Medicaid patients was nearly three times that of physicians treating a large number of Medicaid patients (odds ratio = 2.9) with no differences between physicians and physician assistants. Adjusting for other factors, among waivered providers who treated any Medicaid patient the probability of treating a large number of Medicaid patients was 32% for nurse practitioners and 14% for physicians. Higher patient limits were also associated with a much higher likelihood of treating a large number of Medicaid patients (100 patient-limit odds ratio = 8.4 and 275 patient-limit odds ratio = 30.3 compared with 30-patient limit).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study found that, although the vast majority of Virginia providers are not trained and eligible to prescribe buprenorphine and even the few who are trained and eligible are actually prescribing to Medicaid patients, nurse practitioners may play a critical role in expanding buprenorphine treatment capacity to the Virginia Medical population with opioid use disorder.

Findings suggest that policies supporting nurse practitioners may help to expand buprenorphine treatment capacity for Medicaid patients across the country. This is a similar finding to other studies, which have found that non-physician buprenorphine prescribers play an important role in expanding treatment access to underserved areas and populations, especially rural ones. Nurse practitioners may be better positioned to deliver buprenorphine treatment because they primarily work in settings where this treatment would be most appropriate (e.g., primary care settings).

Assuming Virginia is typical of most states, based on these and similar findings, interventions to increase the supply of buprenorphine prescribers could include and target nurse practitioners. For example, broadening scope of practice laws for nurse practitioners or relaxing state regulations around buprenorphine prescribing that include nurse practitioners could expand buprenorphine treatment capacity. Interventions for nurse practitioners may be especially helpful in rural areas. It is notable that physician assistants are also likely to play an important role in expanding access to buprenorphine but the small number of waivered physician assistants (n = 36) in Virginia may have limited the study’s ability to detect an effect (i.e., limited “statistical power”).

Access to buprenorphine for Medicaid patients is important in improving health outcomes among this vulnerable population. However, this study found that very few qualified providers were waivered to prescribe buprenorphine and, of the few that are authorized, most were not prescribing to Medicaid patients and very few were treating a large number of Medicaid patients.

This is similar to other studies which found that only half of waivered providers actually prescribe buprenorphine and the majority of waivered providers do not prescribe at their maximum limit. In addition, this study found that the largest proportion of buprenorphine prescribers in Virginia were psychiatrists, a specialty that has historically been difficult for Medicaid patients to access. Although increasing fee reimbursements for Medicaid services may offer a partial solution, other interventions are likely needed to increase buprenorphine access for Medicaid patients, such as increasing the number of primary care providers who are authorized to prescribe buprenorphine, encouraging waivered providers to treat more patients, targeted outreach to nurse practitioners and physician assistants, and decreased administrative burden such as removing prior authorization requirements. It is important to note that Virginia underwent a major policy change at the beginning of 2019 when the state expanded Medicaid, which could affect how the study findings are generalized to other states or nationally as well as could have affected the study findings themselves.

While expanding buprenorphine treatment capacity has been shown to increase buprenorphine prescribing to Medicaid patients and this study’s findings suggest nurse practitioners may play an important role in increasing this capacity, multiple barriers must still be overcome.

As noted above, only half of eligible waivered providers prescribe buprenorphine and the large majority do not prescribe at their maximum limit. In addition, like the general population, negative attitudes toward patients with opioid use disorder among healthcare professionals is common, while many healthcare professionals are also not interested or feel ill-prepared in treating opioid use disorder.

Very importantly, new buprenorphine practice guidelines were released by the federal Department of Health and Human Services in April 2021 that no longer require additional training to obtain the waiver. However, qualified providers must still submit a waiver application to SAMSHA and can only treat up to 30 patients unless they undergo the additional training. This may be especially helpful to recruit new nurse practitioners who were previously required to complete 24 hours of training compared to 8 hours for physicians. In addition to directly reducing barriers to obtaining the waiver, there is hope that no longer requiring specialized training will send the message to providers outside specialty programs that they can appropriately manage opioid use disorder by prescribing buprenorphine and following these patients clinically over time. Assuming that having to obtain the waiver training is a significant barrier to prescribing and treating opioid use disorder patients on Medicaid for non-specialist nurses, this might help. But this of course also assumes that practitioners without any addiction training or knowledge of addiction treatment, will be stimulated to prescribe buprenorphine when appropriate, and that the same kinds of therapeutic benefits seen in clinical trials of buprenorphine prescribing for opioid use disorder patients will ensue when prescribed and handled by these non-specialist clinicians. Although the answer to these questions remains unclear, it is possible that mere access to this medication along with regular supportive interactions with a thoughtful and hopefully compassionate clinician could still help.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This is a study done in one state (Virginia) so generalizing these results to other states or nationally should be done with caution. State Medicaid programs can vary significantly.

- This was a cross-sectional study using one year of data (2019) in a state that underwent a major policy change at the beginning of 2019 when Virginia expanded Medicaid. Causality and generalizing these study findings to even the same state in a year other than 2019 are limited.

- This study only examines buprenorphine treatment for one payor type (Medicaid) in Virginia. Although Medicaid represents a sizeable portion (40%) of all patients with opioid use disorder that obtain treatment, prescribers’ propensity to treat individuals with different health insurance types could not be measured.

- Other studies have found an important role of physician assistants in expanding buprenorphine treatment capacity. The power of the study to detect this was limited by a low sample size of waivered physician assistants (n = 36).

- This study may have been vulnerable to the ecological fallacy since population estimates (i.e., county-level covariates) were linked to practice location of individual providers in the model.

- Characteristics of providers that may predict Medicaid participation, such as race/ethnicity, gender, practice type, and practice size, were unavailable and could not be explored in this study. In addition, specialty types for nurse practitioners and physician assistants were unavailable and these providers are probably more likely to serve in settings that might provide buprenorphine treatment (e.g., primary care practice).

BOTTOM LINE

This study linked several administrative data sources to a list of Virginia providers authorized to prescribe buprenorphine in 2019 to examine predictors of prescribing buprenorphine to Medicaid patients. Researchers found that very few qualified providers were trained and eligible to prescribe buprenorphine and, of the few that were authorized, most were not prescribing to Medicaid patients and very few were treating a large number of Medicaid patients. Despite this lack of participation overall by providers, nurse practitioners were more likely to prescribe buprenorphine in this population and thus may play a critical role in expanding buprenorphine treatment capacity to Medicaid patients with opioid use disorder.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Buprenorphine is shown to be a helpful medication in the treatment of opioid use disorder. Many patients will need support beyond medication treatment, such as counseling and services to address social determinants of health like employment, education, and housing. Buprenorphine treatment can be delivered in a private doctor’s office and the medication can be dispensed by a pharmacy, thus making it more flexible and convenient compared with methadone treatment. For Medicaid patients, the good news is that nurse practitioners and other clinicians in addition to physicians are prescribing the medication making it more likely that you will be able to access it if you need it.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Expanding access to buprenorphine is an important tool in addressing the opioid crisis, and nurse practitioners may play a critical role in expanding access, especially to Medicaid patients. The role of nurse practitioners in expanding access to buprenorphine in rural areas may be especially important. In addition to increasing the number providers waivered to prescribe buprenorphine and encouraging these providers to prescribe at their patient limits, there are still many other barriers to overcome in expanding access to buprenorphine, such as addressing healthcare professionals’ negative attitudes, correcting misperceptions about opioid use disorder treatment and recovery, and increasing awareness and knowledge around the scientific evidence for medication treatment for opioid use disorder.

- For scientists: This study used two logistic regressions to model the binary outcomes of any Medicaid participation and treating a large number of Medicaid patients. Researchers found compelling evidence suggesting that nurse practitioners may be playing an important role in expanding access to buprenorphine treatment among Medicaid patients with opioid use disorder in Virginia. More research is needed to see if these results generalize to other states or nationally as well as if these results were impacted by Virginia’s Medicaid Expansion which took place in the same year as this study. It is also unclear exactly why nurse practitioners are more likely to fill this role than physicians. Future studies might include all payor types in order to measure the propensity for different types of providers to treat patients with different types of insurance. Qualitative and survey research may be beneficial in better understanding how to increase Medicaid participation among waivered providers. In addition, there are still many other barriers to overcome in expanding access to, as well as utilization of, buprenorphine, and it is uncertain which policies and initiatives are most critical in increasing buprenorphine prescribing and patient uptake and translating these to reducing ultimate opioid-related harm.

- For policy makers: Buprenorphine is an empirically supported medication for the treatment of opioid use disorder and expanding access to it is an important tool in addressing the opioid crisis. Medicaid covers 4 in 10 people with opioid use disorder in the United States. Therefore, policies and initiatives to increase buprenorphine treatment access among Medicaid patients is likely to improve the health outcomes of this vulnerable population. This study and others suggest that nurse practitioners may play an important role in increasing buprenorphine treatment access among Medicaid patients. Broadening scope of practice laws for nurse practitioners or relaxing state regulations around buprenorphine prescribing that include nurse practitioners could expand buprenorphine treatment capacity. In addition, other measures that might be helpful include policies and initiatives that increase the number of primary care providers who are authorized to prescribe buprenorphine and encourage waivered providers to treat more patients, outreach initiatives to nurse practitioners and physician assistants, and decreasing administrative burden on buprenorphine prescribers such as removing prior authorization requirements. Supporting research to better understand why so few clinicians are prescribing buprenorphine could inform many of these policies and initiatives.

CITATIONS

Saunders, H., Britton, E., Cunningham, P., Saxe Walker, L., Harrell, A., Scialli, A., & Lowe, J. (2022). Medicaid participation among practitioners authorized to prescribe buprenorphine. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 133, 108513. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108513.