Opiate Use Disorder Residential Treatment Outcomes for Young Adults

During the past 15 years, the United States has seen a rapid increase in the rates of chronic prescription opioid and heroin use.

In the scope of this growing problem, emerging adults, ages 18 – 25, stand out for two reasons:

- they have the highest reported rates of use

- they are disproportionately seeking treatment for their opioid use compared to other age groups

While opioid replacement therapy (i.e.,buprenorphine/naloxone or “suboxone”) is considered first-line treatment for opioid use disorders, a recent study showed emerging adults are less likely to remain in treatment, and have poorer outcomes relative to their older adult counterparts.

Given the enormity of the opiate problem in the U.S., it is important to explore several types of treatment, including psychosocial approaches as well as medications.

Schuman-Olivier and colleagues compared 292 emerging adults in residential treatment for a substance use disorder by their opioid use status:

- dependence [OD]

- non-dependent misuse [OM]

- no misuse [NO])

to evaluate substance use and continuing care participation in the year following discharge from the treatment program.

- 25% of patients (n = 73) had an active opioid dependence

- 20% (n = 58) reported opioid misuse in the past 90 days but did not meet the criteria for dependence

- 55% (n = 161) had no history of opioid dependence or misuse in the past 90 days (these individuals met criteria for other substance use disorders (e.g., alcohol, cannabis, stimulants)).

Treatment was based on the 12-step Minnesota Model and also used motivational enhancement, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and family-based therapeutic approaches. Patients were assessed at baseline, end of treatment, and 3, 6, and 12 months after discharge. The average length of stay in treatment was 26 days, and 84% of discharges were staff approved. The three groups were similar on all demographic characteristics at the start of the study. 95% of participants were Caucasian, about 75% were male, and all were single. The average age was 20 years.

Regarding clinical variables at admission, OD had significantly higher levels of dependence severity than both OM and NO, and OM was significantly more likely to meet the criteria for polysubstance dependence than the other two groups. OD was more likely to report heroin as the only form of opioid used recently, while OM was more likely to have recently only used prescription opioids.

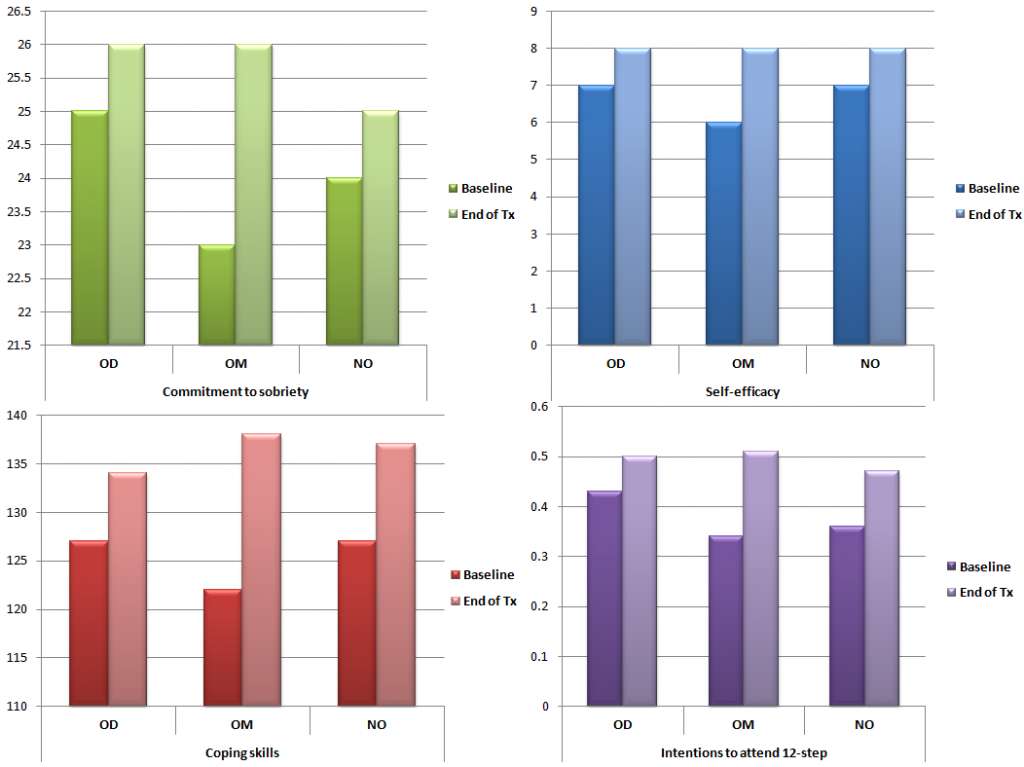

During treatment, all groups showed significant beneficial increases in psychological variables which are often the target of psychosocial treatment, such as levels of commitment to sobriety, abstinence self-efficacy, coping skills, and intention to attend 12-step mutual help organizations, as well as significant decreases in psychiatric symptoms (see figure below).

What was surprising was that the opioid dependent (OD) group had a continuous abstinence rate that was much higher than that seen in studies involving young adults receiving suboxone.

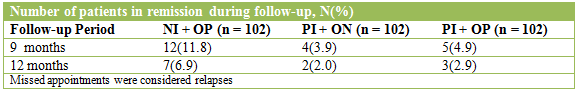

The opioid dependence (OD) group attended significantly more outpatient sessions than no misuse (NO) during follow-up. Non-dependent misuse (OM) reported more substance use and lower abstinence rates than the other two groups during the 12-month follow-up period.

Additionally, the use of substances (e.g., cannabis, alcohol) for all participants increased significantly over time, suggesting that the benefits of single episodes of acute treatment diminish over time, and more effective ways of engaging young adults in some form of continuing care are needed.

IN CONTEXT

In light of the recent opioid epidemic, it is important to consider all potentially effective treatment options as some individuals might not want to try medications like suboxone. They also may have other risks (e.g., suicidal intent) or be suffering from additional psychiatric problems that may necessitate a residential stay.

While many have expressed concerns about residential treatment for this population due to high rates of relapse after treatment discharge, this study showed emerging adults may benefit from this option provided it includes linkage to and engagement in continuing care.

The current study showed that an extended-release naltrexone implant may provide an evidence-based strategy to increase treatment retention and reduce relapse. Importantly, it provides a longer window of protection relative to the month-long injection formulation approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (i.e, Vivitrol).

Those with opioid dependence rather than misuse represent a group who may benefit from this form of treatment as they were more likely to engage in outpatient care during follow-up and had higher than usual abstinence rates. However, the drop in those who were completely abstinent at six months compared to twelve months shows the importance of follow-up care to maintain the benefits achieved during residential treatment.

Those who misuse opioids but do not meet dependence criteria may require special clinical attention. These individuals had higher addiction severity and consequences relative to those without opiate use – associated with heightened relapse risk – but less than those with dependence, suggesting limited insight about this increased risk.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Consider residential treatment with a commitment to engage in continuing care. Continued support after treatment can help engage and prevent future relapse.

- For scientists: Due to the observational nature of this study, it is important to examine residential treatment options through experimental methods. Next steps include a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing residential treatment, buprenorphine/nalxone, and perhaps a combination of the two.

- For policy makers: Support for residential treatment may enhance the outcomes experienced by young adults with opioid use disorders. While additional evidence is needed from future studies, residential treatment programs present an option that may warrant increased funding.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: If you are treating an emerging adult who has not benefited from outpatient opioid replacement therapy in the past, residential treatment may be an appropriate option.