Overdose, first responders, then naloxone: What’s next?

Overdose rates are at an all time high despite increased funding and policy support. There are persistent gaps in the continuum of care that lead to differential treatment access. Some individuals will not be transported to an emergency department following overdose, and if they are, many emergency departments do not initiate lifesaving medications to prevent future overdose. It is important to identify novel ways of linking individuals to frontline treatment options. In this study, the research team examined a linkage to treatment initiated by first responders with encouraging findings.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Pharmacotherapy with an opioid agonist or antagonist is considered primary treatment for opioid use disorder. Abundant evidence shows that medication reduces opioid use, opioid use disorder-related symptoms, provides overdose prevention, withdrawal symptom relief, craving reduction, reduces infectious disease transmission, and criminal behavior associated with drug use without producing the same euphoria. Despite the efficacy of this lifesaving tool, overdose rates remain high and gaps in the continuum of care exist. For example, only about one quarter of individuals seek treatment following a nonfatal overdose even though they are at high risk for a subsequent fatal overdose. It is critically important to engage individuals with treatment as quickly as possible.

First responders who administer naloxone (i.e., overdose reversal) are sometimes the only medical intervention people receive and represent the first point of care to link people to treatment. However, there is often no standard treatment linkage protocol for first responders to rely on.

In this study, authors tested the feasibility of a pilot experiment called “RIMO” (Recovery Initiation and Management after Overdose) to contact, screen, enroll and link individuals into treatment following the release of their contact information from emergency medical services.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Study Design

This was a randomized trial with 33 participants who were successfully contacted, screened, enrolled into the study, and assigned to the either the control group (n=17) which received a brochure of resources following a baseline assessment or assigned to the treatment linkage intervention group (RIMO) (n=16).

Study Protocol

The trial starts with after emergency medical personnel administer an overdose reversal. Personnel get permission to release the individuals contact information to people (i.e., study staff) who will follow-up to see how they are doing and talk about available health care services. Upon receipt of the authorization form a linkage manager attempts to contact the individual to set an appointment to screen for study eligibility. The eligibility criteria included: no current treatment utilization; weekly use of opioids; residence in Chicago; and cognitive capacity to consent to the study procedures. They then would receive a baseline assessment and group assignment. Individuals assigned to the intervention immediately met with a linkage manager to engage them in a discussion about their willingness and benefits of using treatment, receive personalized feedback from the assessment, address ambivalence and commitment, problem solve barriers, schedule a treatment appointment, and develop a reminder schedule. Linkage managers contacted participants 2-3 times/week for 4 weeks to ensure they complete detox and/or initiated and remained in treatment. This includes working with treatment providers to minimize missed doses.

The research team wanted to determine whether participants in the intervention group compared to the control group were equally likely to receive any kind of treatment, medication treatment specifically, receive the same number of days of medication, and receive medication at 30 days post-study randomization. The researchers also conducted a focus group at the end with intervention participants only in order to obtain their perspectives on the intervention process.

Study Recruitment

Ultimately the study had 75 overdose contacts that resulted in 33 people who actually participated in the study which equals a conversion rate of 2.27 to 1. Of the 75 contacts who overdosed, 51 individuals were alert, oriented, and provided contact information,42 of which were located and came to the research office for screening, 33 of which were eligible and agreed to be assigned to either group.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Intervention vs. Control Group

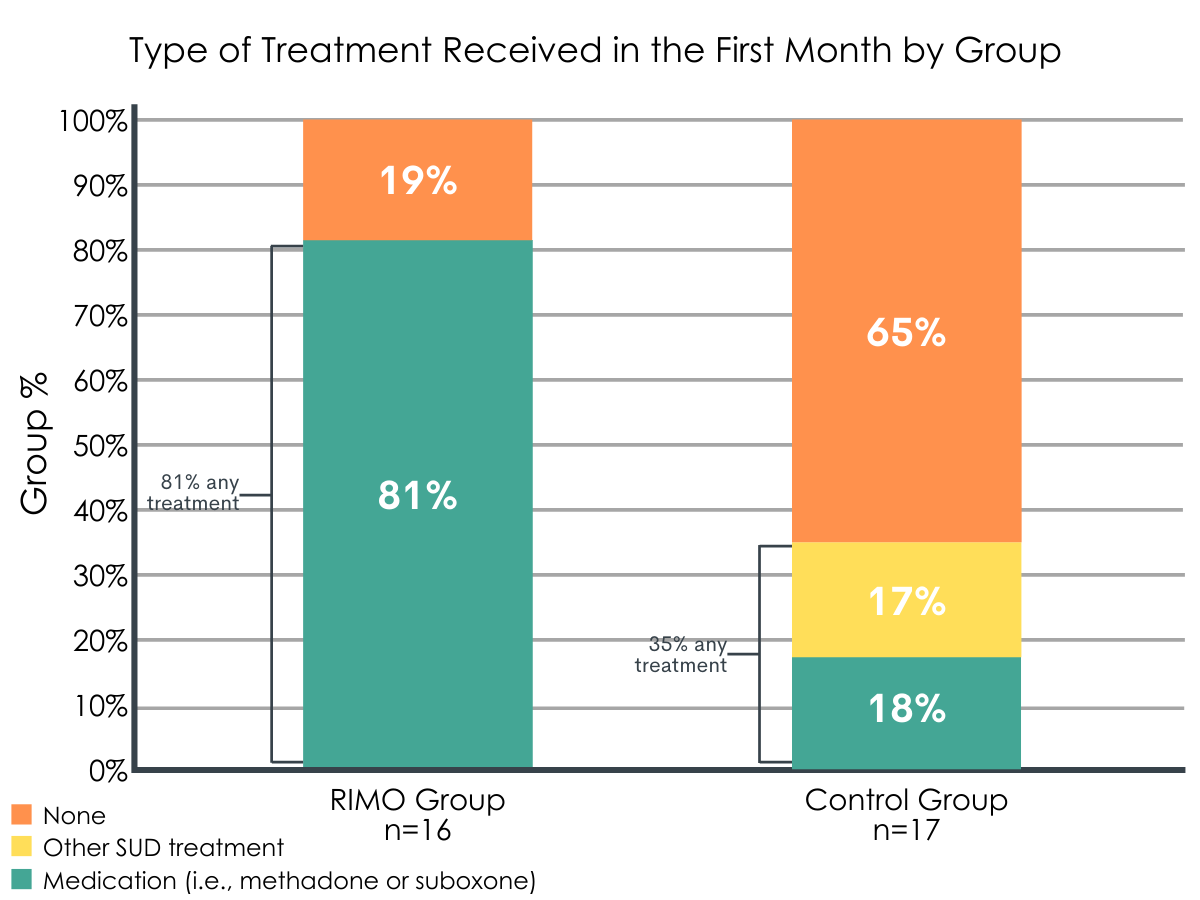

Individuals assigned to the intervention (n=16) were 8 times more likely to receive any kind of treatment (81% vs 35%), 20 times more likely to receive medication treatment, specifically (81% vs. 18%) and receive more days of medication (11.19 vs. 0.76) relative to those in the control group. In addition, intervention participants were more than 12 times as likely to be receiving medication at 30 days post-study randomization (44% vs. 6%).

Figure 1. Type of treatment received in the first month by group.

Qualitative Analysis

1) Initial contact with Emergency Medical Services.

“Cuz this one ambulance guy picked me up twice, he’s like you’re gonna kill yourself man, let me introduce you to these people. Sign this and I’ll help you. And so I signed off on it, and like I said, they made a call, I was deep on the Westside when you came and got me.”

2) Assertive outreach and engagement through interactions with the linkage managers.

“Probably because I didn’t want to be bothered so I gave them a bogus phone number and they didn’t give up and were at the house and said I’ll take you now. Yeah and without them I wouldn’t be alive today because they kept at it… they called me at least every other day just to see how I was doing and people need that, you know, when you’re lost so badly, you need someone just to call and check on you to see how you are.”

3) Persistent follow-up to facilitate access to treatment.

“I was on destructive path, but after meetin’ me, meetin’ them, steady follow-up and they follow-up, and they followed up, and they followed up, and the followed-up man, I surrender, you know I’m sayin’? Let’s go, let’s get it, let’s get it in, let’s do this! If you gonna help me get in, let’s get it. I’m ready to get in here, I’m ready to get my life together.”

4) How RIMO intervention differs from other interventions.

“Lighthouse has been a blessin’ to me too. When I first came here I was still out there usin’ drugs, but Lighthouse really cared. They send people to look for you and try to find you and it seem like every time he would find me in my madness… This place really cares… the other places they just want you for that bed spot.”

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The RIMO treatment linkage intervention addresses a significant challenge to the field, specifically linking individuals to treatment immediately after an opioid overdose by using assertive and proactive outreach and engagement strategies. Lifesaving treatments for opioid use disorder exist so the important question that arises is how to increase treatment utilization.

First, 81% of those in the intervention group received some kind of treatment compared to just 35% in the control condition. Second, 81% received medication treatment, specifically, compared to only 18% of the control group. Pharmaceutical options for opioid use disorder are considered “best practice”, front-line, treatments and increasing utilization prevents lethal overdose which has been the defining tragedy of the current opioid crisis.

The study shows feasibility of several components of the intervention, the first of which is obtaining consent to release contact information from individuals who just received an overdose reversal and thus are experiencing a significant degree of stress. In fact, of the 75 authorization forms completed by emergency service providers, only 9 people refused and 2 were not yet alert.

The second point of demonstrated feasibility is building collaborative partnerships with emergency service providers. Naloxone is increasingly being used by police officers, emergency medical technicians, and other first responders to reverse opioid drug poisonings; however, there is often not a consistent protocol for referring individuals to treatment. Their collaboration was made possible by their willingness to briefly train with study staff and take the additional step to transmit contact information after administering naloxone. Lastly, this linkage intervention demonstrates the feasibility of locating individuals through assertive outreach and meeting with them soon after receiving an overdose reversal (74% within 7 days).

Substance use disorder is a treatable illness, and when approached using a continuum of care framework as opposed to brief episodic medical intervention alone, it can facilitate and increase the chances of treatment engagement and, potentially, ongoing recovery management to address the disorder over time. First responders who offer treatment linkage following an overdose reversal (i.e., medical intervention alone) are providing a continuum of care and engaging in an evidence-based practice that is likely to save lives.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The small sample size of this pilot study and the effect sizes it yields may not represent effect sizes from a larger implementation.

- There are challenges to integrating research procedures within real-world operations. The requirement of emergency medical personnel to scan and email the authorization form was a potential barrier to rapid transmission given 60% of the forms were received by the study team within 1 day.

- Treatment received was based on self-report at a 30-day follow-up and was not verified with treatment organizations unlike the date of admission.

- No information on cost-to-benefit is available. Given the importance of linkage managers’ persistence identified in the qualitative component, a cost to benefit analysis that considers the necessary time component could better illuminate the intervention.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: You or someone you know may have an opioid use disorder or be at risk for overdose. Seeking treatment early and often is likely to yield improved functioning and reduced opioid use but only about 25% of people use treatment after surviving an overdose. This study tested the effectiveness of a linkage intervention to get people into treatment following an overdose reversal administered by first responders. By using assertive outreach, engagement, and persistent follow-up 81% of those in the RIMO intervention group received treatment compared to 35% in the control condition.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Medications for opioid use disorder are considered to be the most effective treatments available. Only about 25% of people engage with treatment following a nonfatal overdose which highlights the need for better treatment linkages. This study tested a linkage intervention for individuals who experienced an overdose and were administered naloxone (i.e., overdose reversal medication) by first responders. 81% of individuals in the RIMO intervention group went on to receive medication treatment compared to only 18% of the control group who received a brochure of local resources instead of the intervention.

- For scientists: This study addresses a central challenge to reducing the high rates of opioid overdose – linking individuals to treatment following an overdose reversal. This pilot study tested an intervention that combined assertive outreach to individuals following an opioid overdose reversal by emergency medical services, treatment linkage, and engagement. The RIMO intervention group had substantially higher odds of receiving any treatment for opioid use (odds ratio=7.94) and any medication for opioid use disorder (odds ratio=20.2) and received significantly more days of opioid treatment (15.2 vs. 3.4) and more days of medication in the 30 days post-randomization (11.2 vs. 0.76) relative to the control group. Larger, confirmatory, studies are needed but this intervention shows great promise.

- For policy makers: This pilot study evaluated the feasibility of the Recovery Initiation and Management after Overdose (RIMO) intervention to link individuals to medication treatment following an opioid overdose. The study team worked with emergency medical service teams to request permission from individuals after an opioid overdose reversal to release their contact information and individuals were subsequently contacted for participation. The novelty of this approach is that it can be done even if individuals refuse transport to an emergency department (and thus fail to receive treatment linkage). The intervention group had higher odds of receiving any treatment for opioid use (nearly 8 times more likely) and any medication for opioid use disorder (20 times more likely) and received significantly more days of opioid treatment (15.2 vs. 3.4) and more days of medication in the 30 days that followed (11.2 vs. 0.76) relative to the control group. Larger, confirmatory, studies are needed but this intervention shows great promise.

CITATIONS

Scott, C.K., Dennis, M.L., Grella, C.E., Nicholson, L., Sumpter, J., Kurz, R., & Funk, R. (2020). Findings from the recovery initiation and management after overdose (RIMO) pilot study experiment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 108, 65-74. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2019.08.004