Oxford Houses offer both recovery benefits and cost savings

Recovery residences, such as Oxford Houses, are often a life-saving recovery support service for many, providing safe and supportive environments to stabilize and build optimism and resilience. This study is the most rigorous evaluation of Oxford Houses and recovery residences more generally to date.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

First developed in 1975, Oxford Houses are a type of abstinence-focused recovery residence that are democratically-run, where residents are entirely responsible for house decisions and maintenance. There are approximately 2,000 Oxford Houses in the U.S. and other countries, supporting 24,000 individuals per year. This series of studies by Jason and colleagues – the most rigorous to date on this topic – examined the effects of Oxford House participation on several recovery-related outcomes among individuals who attended residential substance use disorder treatment. This study sought to answer the questions:

- Is Oxford House participation helpful?

- Who are Oxford Houses most helpful for (e.g., older vs. younger individuals)?

- Can Oxford Houses reduce the financial burden caused by substance use disorder?

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Authors assessed 150 individuals discharged from residential substance use disorder treatment in Illinois every 6 months for 2 years (i.e., assessments at 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months). Half of the group (n = 75) was randomly assigned to the Oxford House condition, and the other half (n = 75) were randomly assigned to usual continuing care (i.e., the usual professional or mutual-help organization services received after treatment).

- MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

Apart from the initial random assignment to each of these conditions, participants were free to engage in other recovery support services as they wished. Thus, after individuals assigned to the Oxford House condition were brought to one of 20 residences across the state, current members voted on whether they could become a resident, as per Oxford House policy. Only one research participant was rejected by vote initially, though research staff subsequently brought this person to another house, who approved his/her residence.

Of note, members were able to stay or leave the residence voluntarily – 95% moved out of their respective Oxford Houses at some point over the 2-year study, for example. For those assigned to usual continuing care, case managers at the treatment center referred individuals to different combinations of outpatient treatment, mutual-help, and other community resources. The majority of usual care participants lived in their own home, or the home of a spouse/partner, relative, or a friend (67%). Nearly 20% lived in a non-Oxford, professionally staffed recovery residence.

The groups were compared on four primary outcomes across the entire 2-year study period:

- Substance use abstinence (yes or no in the past 6 months; self-reported alcohol and other drug use was validated by an identified significant other at the final, 2-year follow-up only)

- Criminal charge(s) (any: yes or no in the past 30 days)

- Employment (any full-time or part-time work in the past 30 days: yes or no)

- Self-regulation in daily life (36-item self-report scale where participants indicated the extent to which statements reflected who they are, such as “I am good at resisting temptation”, “I never allow myself to lose control”, and “I’m not easily discouraged”)

Given that individuals who are younger and/or have a co-occurring psychiatric disorder, often have poorer outcomes compared to older individuals and those with only a substance use disorder, respectively, authors also tested whether Oxford House participants did better or worse than usual care participants depending on their age (37+ years old versus 36 years old or younger) or whether they had a lifetime diagnosis of anxiety or mood disorder (according to the fourth edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM IV). Finally, just among Oxford House participants, they tested if individuals who stayed in the recovery residence for 6 or more months had better outcomes.

Oxford House and usual care participants were initially similar on the four primary outcomes (e.g., 6.7% in each group were abstinent before entering treatment) as well as on demographic characteristics, which is to be expected in a randomized trial of this size. Overall, 62% were women, and Black individuals were well represented, comprising 77% of the sample, compared to 11% White, and 8% Latino. The average participant had 12 years of education, corresponding with a high-school diploma, and 44% entered the study with a history of criminal justice system involvement. Six out of 10 participants had a co-occurring mood or anxiety disorder in their lifetime, while 28% reported a history of having taken psychiatric medication, 27% had attended inpatient substance use disorder treatment (before the residential treatment episode that preceded entry into the study), 28% attended outpatient treatment, and 8% had attempted suicide. Information regarding participants’ substance use history, including substance use disorder diagnosis, was not reported.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

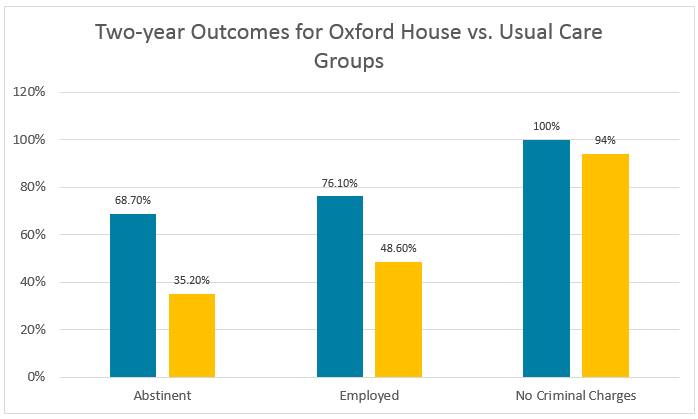

Oxford House participants had better outcomes over time across the board, even when models adjusted for participant gender, age, and the presence of a co-occurring psychiatric disorder. In addition, Oxford House participants also had greater increases in self-regulation over time.

Individual characteristics determined criminal charges, as younger participants fared better in Oxford Houses, and older participants without a co-occuring disorder did equally well in both Oxford House or usual care groups. For all three other study outcomes (including abstinence), Oxford House outperformed usual care regardless of age or diagnostic status.

Importantly, when looking only at Oxford House participants, individuals who stayed there for 6 or more months had much better abstinence rates (84 vs. 54%). This added benefit of a 6-month or longer stay was especially true for younger individuals. Employment is can be a particularly important outcome for young adults, and of note, 94% of younger patients with 6+ months in an Oxford House were employed at the 2-year follow-up vs. 56% who stayed for less than 6 months.

ARE OXFORD HOUSES COST EFFECTIVE?

The public health significance of these findings are further enhanced by data from a related study by the same research team, who evaluated cost-effectiveness of Oxford Houses in the same sample of individuals.

- MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

They examined 129 of the 150 individuals that had sufficient data to carry out the analyses.

Authors measured costs based on the following:

- stay at Oxford House (weekly average cost = $99)

- treatment utilization and mutual-help meetings (accounting for time they could have spent working, earning minimum wage each day of treatment or mutual-help meeting $8 x 8 hours = $64 cost per day of service utilized).

They measured financial benefits from both personal and societal perspectives based on the following:

- self-reported monthly income

- self-reported days engaged in illegal activities in the past month ($754.93 per illegal activity)

- abstinence in prior 90 days ($185.74 saved for alcohol abstinence and 738.92 saved for drug abstinence every 6 months)

- no incarceration ($23,812 saved for a 6-month period per incarcerated individual)

Financial gains for Oxford House participants far outweighed costs ($32,200 more), primarily driven by reduced illegal activity.

This was even true despite greater average cost per each participant over 2 years ($3200 more). All told, the net benefit of being assigned to the Oxford House condition versus usual care was $29,000 per person during the 2-year study.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This series of studies on Oxford Houses by Jason and colleagues is the most rigorous evaluation of recovery residences to date. Overall, for individuals completing residential substance use disorder treatment, Oxford Houses provided substantially greater benefit over time, not only in terms of abstinence rates but also in employment and criminal justice outcomes.

Emerging adults (e.g., ages 18-29) are often at greater risk for relapse, in part due to their riskier social networks where alcohol and other drugs are more prevalent. Participation in an Oxford House for 6 months or more, may offer a substance-free community that helps promote engagement in recovery-related activities.

- MORE ON A RELATED STUDY

-

In another study specifically on 18-24 year old individuals who attended residential treatment, for example, recovery residence participation was uniquely related to better abstinence rates during the first post-treatment year, beyond participation in residential treatment, outpatient treatment, and mutual-help organizations. It is worth highlighting also that longer Oxford House stays in this study were associated with extremely high rates of employment for younger individuals, who may otherwise struggle to meet important adult milestones like financial independence.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Individuals for this study were recruited after being discharged from residential treatment. More research is needed to evaluate the benefits of Oxford Houses for other types of individuals.

- Oxford Houses are a specific type of recovery residence, with fairly rigorous levels of quality control, and a specific democratically-run system of house governance. While other studies have examined different types of recovery residences (e.g., Sober Living Homes), less is known about whether staying in these other types of residences produces similar recovery benefit.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Oxford House participation after treatment is not only likely to improve one’s chances of recovery, employment, and reduced criminal activity, but, on balance, it is also likely to help financially as well. While more research is needed on how long one needs to stay at an Oxford House residence, some preliminary research suggests added benefit with at least a 6-month stay.

- For scientists: This series of studies is the most rigorous evaluation of recovery residences to date. They suggest not only that Oxford Houses are beneficial, but also cost-effective, recovery support services. Jason and colleagues provide a helpful model by which other recovery support services may be evaluated, including a cost-benefit analysis to understand the potential societal impact of linking more individuals to these widely available services available in local communities.

- For policy makers: Oxford Houses not only help promote recovery-related benefit, but also help address the financial burden of substance use disorder. Based on this series of studies by Jason and colleagues, policies that support greater access to, and linkage with, recovery residences are warranted.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Oxford Houses are beneficial, but also cost-effective, recovery support services. Particularly for providers in residential treatment settings, Oxford Houses should be considered a central continuing care resource to which patients can be referred after discharge. More research is needed on the recovery-related benefit offered by other types of recovery residences.

CITATIONS

Jason, L. A., Davis, M. I., & Ferrari, J. R. (2007). The need for substance abuse after-care: Longitudinal analysis of Oxford House. Addictive Behaviors, 32(4), 803-818.

Lo Sasso, A. T., Byro, E., Jason, L. A., Ferrari, J. R., & Olson, B. (2012). Benefits and costs associated with mutual-help community-based recovery homes: The Oxford House model. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35(1), 47-53.