For individuals receiving mental health treatment, screening with brief intervention reduces heavy alcohol and stimulant, but not cannabis use

Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is a common strategy for engaging patients with unsafe drinking in intervention and specialty care. Alcohol and other drug use can interfere with mental health treatment. This study provides a first look at outcomes of SBIRT implemented within mental health clinics, and regarding alcohol, cannabis, and stimulant drug use among patients with co-occurring psychiatric disorders.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

SBIRT is designed to screen for, and reduce, unsafe substance use. For those in need, these interventions are also designed to actively link patients to specialty addiction care. Most research focuses on SBIRT as delivered within primary care settings, targeting unsafe drinking among patients, irrespective of co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses. Research on these scalable strategies may be of particular relevance, however, for those with psychiatric disorders. Individuals with mental health conditions are at substantially greater risk for harmful drinking and other drug use, while substance use can interfere with the course of mental health treatment. In this study, Karno and colleagues examined the effectiveness of SBIRT as implemented within mental health clinics, and regarding alcohol, stimulant, and cannabis use, and referral to specialty substance use disorder treatment compared to a Health Education control condition. As such, this study addresses important questions about the implementation and effectiveness of SBIRT among underserved patients with co-occurring psychiatric disorders.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a multisite, two-group randomized clinical trial comparing a screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) intervention to a Health Education comparison condition. The researchers used a block randomization approach in which they grouped participants into “blocks” or groups based on participants’ primary psychiatric disorder, primary substance of use (alcohol vs. cannabis or stimulants), and gender. The researchers then randomized individuals to SBIRT or Health Education conditions one to one from within these blocks to ensure that participants from different blocks were evenly divided between the two study conditions, accounting for any undue influence these factors might have on the comparison between the intervention and control group. The study sites included two mental health treatment settings in Ventura (community-based outpatient clinics) and Los Angeles counties (university-based healthcare settings), California.

Participants included 718 patients who were 18 years old or older, with a current psychiatric disorder diagnosis (i.e., major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, or psychotic disorder) and reported one or more heavy drinking days or any use of cannabis or stimulants in the 90 days leading up to the trial. Patients reporting opioid use were included as well so long as they met alcohol, cannabis, or stimulant use criteria. Patients were excluded if they were homeless or had unstable housing, were under the influence of substances at study enrollment, or received previous behavioral or pharmacological treatment for substance use disorder in the previous 90 days.

SBIRT was delivered in this study during a single, in-person session with a Master’s-level clinician. The clinicians used the WHO ASSIST measure to screen alcohol, cannabis, and stimulant use severity. Participants who scored in the moderate or high-risk range received brief intervention (including motivational interviewing, normative feedback about their use, advice, empathy, support for self-efficacy); participants who scored in the high-risk range also received a referral to specialty substance use treatment. Referrals could be accompanied by a listing of treatment options and/or a “warm hand-off” to staff at the substance use treatment site. The Health Education comparison condition included manualized health education focused on health and wellness, and was not specific to substance use. The researchers gathered data from participants at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months to evaluate changes in alcohol, cannabis, stimulant use, and rates of referral to treatment.

Participants in the study included 718 patients. The average age was 33.8 (SD = 12.6). About half (51%) were men, White (53%), and the majority were unemployed (72%); the average number of years of education reported was 13.7 (SD = 2.6).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

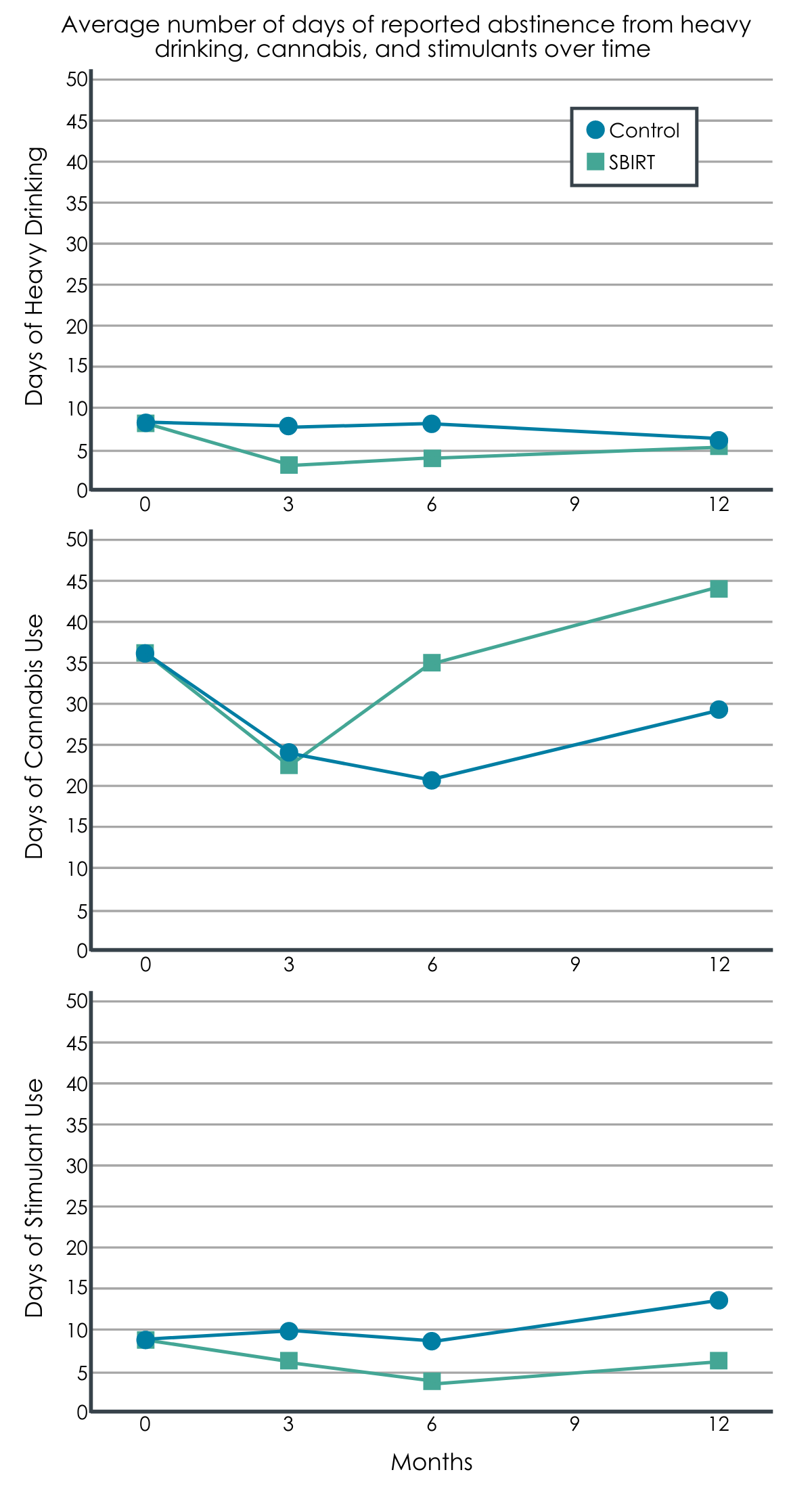

Compared to patient in the Health Education control condition, patients who received the screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) intervention reported fewer heavy drinking days and stimulant using days at 3 months, and sustained improvements at 6 and 12 months.

Figure 1.

There were no differences between groups regarding cannabis use by 3 months, and some evidence that cannabis use was higher among patients who received SBIRT by 6 and 12 months. There were no observed differences between the groups regarding past 90-day abstinence rates at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Nearly 23% of patients received specialty substance use disorder treatment services within 30 days of study enrollment. There were no differences between the treatment groups in the rate of substance use treatment engagement, number of services utilized, or sessions attended.

Figure 2.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) was associated with improved alcohol and stimulant use outcomes among patients with co-occurring psychiatric disorders already engaged in mental health treatment. These results are unlike those showing SBIRT as a generally ineffective approach for drug use delivered within primary care settings. One difference could be that the current study implemented SBIRT within mental health clinics, focused on patients with co-occurring psychiatric disorders, and the fact that patients were already engaged in mental health treatment relative to other studies wherein SBIRT is delivered as a standalone intervention. It is also possible that patients in the current study were more motivated for change by virtue of already being engaged in treatment.

The researchers did not observe improvements in cannabis use by 3 months but did find that cannabis use was higher among patients in the SBIRT condition compared to the Health Education control condition by 6 and 12 months. This might reflect legislative changes that legalized cannabis use in California during data collection. The uptick in cannabis use could have also been compensatory, and might have increased in response to decreases in alcohol and stimulant use. Particularly given the changing legal landscape of cannabis across the US, and greater levels of cannabis use among those with mental health conditions, studies of the impact of cannabis use on the course of mental health treatment will be critical.

Nevertheless, the net positive effects of SBIRT observed, coupled with its brevity and ease of implementation in the context of normal clinic operations, provides further promise of regarding the efficacy of SBIRT. These findings are especially noteworthy given the fact that there remains significant unmet mental health and substance use treatment need among patients with co-occurring substance use and other psychiatric disorders.

The researchers did not find that SBIRT was associated with higher rates of substance use disorder treatment engagement. The authors did not report information about the types or quality of treatment patients received within the mental health clinics from which they were recruited, or comment on the possibility that patients might have received substance use disorder treatment as part of usual care within these clinics. It is possible that similar rates of substance use disorder treatment-seeking between conditions related to practical barriers of attending additional treatment that impacted both groups of participants, and the possibility that their current treatment might also be targeting, at least to some degree, their substance use.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The study focused on self-report of alcohol, cannabis, and stimulant use in the past 3 months using validated methods; however, results might differ from reports gathered more frequently then every 3 months.

- As with most-all non-medical trials, the authors were unable to ensure that the study condition was masked from participants in the study; they also did not specify whether their research assessments were performed by personnel who were masked to study condition.

- The current study focused on clinical outcomes and provided less information regarding implementation of the intervention across the study sites.

- The authors implemented their trial within mental health outpatient clinics using patients currently engaged in care, but do not provide information about the duration, intensity, or types of interventions provided to patients outside of the SBIRT and Health Education interventions tested.

BOTTOM LINE

In this large-scale randomized clinical trial, the researchers found that alcohol and drug screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) was associated with reduced alcohol and stimulant use among patients already engaged in mental health treatment—a significant value added to their care. The SBIRT intervention was not associated with improvements in cannabis use, and by 6 and 12 months, cannabis use was higher in the SBIRT condition compared to the Health Education control condition. The SBIRT intervention and health education comparison groups, however, were similar on engagement with specialty substance use disorder treatment.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is a method of quickly assessing substance use, providing motivationally-based support and intervention to help patients reduce their substance use, and provide referrals as needed. SBIRT is most often implemented in medical and primary care settings, but this study demonstrated that it can be effective even for patients already engaged in mental health treatment, and who have other psychiatric diagnoses, such as depression or schizophrenia. While more intensive substance use disorder treatment is recommended for moderate to severe substance use disorder, according to this study even a single session of brief intervention may be associated with lasting reductions in substance use.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Most often SBIRT is implemented within medical and primary care clinics. However, these researchers implemented SBIRT within outpatient mental health clinics, and evaluated its effectiveness among patients with at least one co-occurring psychiatric disorder. While they did not observe higher rates of substance use disorder treatment engagement following receipt of SBIRT, they did find that patients in this condition were significantly more likely to reduce their alcohol and stimulant use compared to patients who only received Health Education. On the other hand, cannabis use appeared to be higher in the SBIRT condition by six and 12 months, suggesting that it may not be efficacious for cannabis use, or at the very least that ongoing monitoring of cannabis use is indicated.

- For scientists: There is inconsistent support for SBIRT in the empirical literature, largely attributable to barriers to proper implementation and fidelity of intervention delivery within clinics. Nevertheless, in this study the researchers demonstrated efficacy of SBIRT regarding heaving drinking and stimulant use among mental health outpatients with a co-occurring psychiatric disorder. These results are promising despite higher levels of cannabis use and null findings regarding rates of substance use treatment engagement among those referred for treatment. Further research is recommended to examine reasons for both. Increases in cannabis use might relate to the legalization of cannabis in California during the study period, increasing cannabis use as patients decreased their use of other substances; and null referral and substance use treatment engagement results might relate to the fact that patients were recruited from and already engaged with outpatient mental health treatment services.

- For policy makers: Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) represents a promising intervention and referral model with demonstrated efficacy in a range of medical and mental health treatment settings. While more intensive intervention is often needed for patients with substance use disorder and other co-occurring psychiatric disorders, ongoing investment in SBIRT initiatives in psychiatric clinics seem worthwhile given its potential to reach patients who might not otherwise receive substance use intervention, or know about recommended treatment options.

CITATIONS

Karno, M. P., Rawson, R., Rogers, B., Spear, S., Grella, C., Mooney, L. J., . . . & Glasner, S. (2021). Effect of screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment for unhealthy alcohol and other drug use in mental health treatment settings: A randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 116(1), 159–169. DOI: 10.1111/add.15114