Do people stigmatize individuals with opioid use disorder even when their addiction arose from opioids prescribed for pain?

There is growing public awareness around the problem of opioid use disorder and greater knowledge of the role that opioids prescribed for pain management initially played in the opioid overdose crisis. Studies examining public attitudes specific to opioid use disorder associated with the initial medical use of opioids can help to inform public health policy and messaging. The authors of this study explored societal perceptions of individuals who developed opioid use disorder following physician-prescribed opioids for pain.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Substance use disorder is among the most stigmatized of all psychiatric or medical conditions worldwide. Compared to other conditions, substance use disorder is disproportionately more likely to be attributed to bad character and associated with violent and unpredictable behavior. Further, people with substance use disorder are perceived as more blameworthy, and less deserving of help than those with other stigmatized conditions. To date, however, studies on substance use disorder stigma have typically not considered subgroups of individuals with addiction, such as those who developed opioid use disorder following prescribed opioid use for pain, in contrast to those who developed opioid use disorder as a result of illicit opioid use.

Because of the increasing awareness of opioid use disorder in the United States (US) arising from the current opioid overdose crisis, and recent high-profile legal proceedings against pharmaceutical companies producing certain opioid medications, there is reason to believe societal perceptions of individuals with opioid use disorder may differ by subgroup.

This study explored US societal attitudes toward individuals who developed opioid use disorder following prescribed opioid treatment of pain and contrasted these with societal attitudes toward individuals with major depression, schizophrenia, alcohol use disorder, and subclinical distress.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a randomized study of 1,173 participants who completed the 2018 National Stigma Studies–Replication II (NSS-RII) module of the General Social Survey, a nationally representative public opinion survey of non-institutionalized adults living in the continental US. To examine public knowledge of, and response to mental illness, respondents were randomly assigned to respond to one of the five vignettes describing someone with one of the following conditions: 1) opioid use disorder arising from prescribed opioids for pain, 2) alcohol use disorder, 3) major depression, 4) schizophrenia, or 5) subclinical distress. The ‘subclinical distress’ comparison (i.e., distress not meeting criteria for a mental health or substance use disorder) was provided to observe differences in public attitudes associated with distress in general, relative to a clinically significant condition characterized by more severe impairment.

The General Social Survey uses a stratified random sample method to select a sample of study participants representative of the broader US population. So, although these study results are based on 1,173 study participants, the findings can be thought to generalize to the entire US population.

Figure 1. Vignette example read by study participants.

Respondents were asked a series of questions related to the following:

- How probable is the vignette character to be experiencing a ‘mental illness’, a ‘physical illness’, or just be experiencing ‘part of the normal ups and downs of life’.

- Desire for social distance from vignette character measured using six items scaled together, including willingness to…. move next door to vignette character, spend an evening socializing with, make friends with, or work closely with the vignette character, have a group home in the neighborhood for such individuals, and have the vignette character marry into the participant’s family.

- Perceived dangerousness of the vignette character measured with two items asking how probable it is that the character would do something violent toward other people or toward themself.

- Competence, measured by respondents’ perception of the vignette character’s ability to manage their own money and make treatment decisions on their own.

- Need for treatment coercion indicating whether the vignette character should be forced by law into any of five different types of treatment.

- Respondents were also asked about causal attributions via questions asking how probable it is that the vignette character’s condition was caused by a series of six factors, including bad character, a chemical imbalance in the brain, the way s/he was raised, stressful life circumstances, or a genetic or inherited problem.

To facilitate interpretation of results, the authors dichotomized ordinal outcomes, combining two categories representing moderate or strong agreement (equal to 1) or moderate or strong disagreement (equal to 0).

The 2018 survey used in this study had a response rate of 59.5%. Survey weights were used to address non-response bias, which could result from 40% of the public declining to participate. Up to 8% of participants’ data (n = 90) were dropped due to missing data.

The final sample (n = 1,083) was on average 49 years old, 51% female, 72% White, 17% Black and 11% other race. Approximately 13% of participants had less than a high school education, 27% had a high school diploma, 26% had some college and 34% had a 4-year college degree or more.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

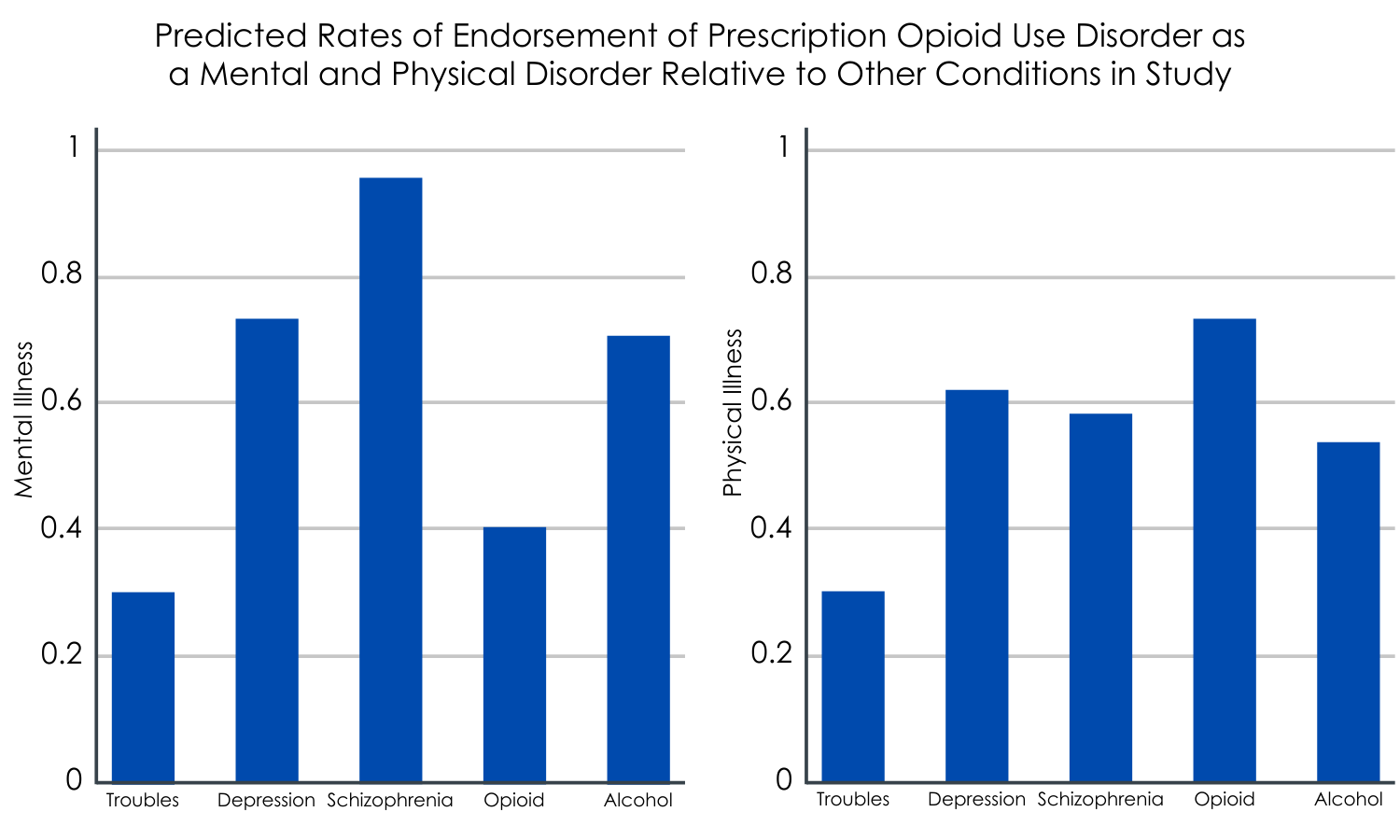

Figure 2.

Those with prescription opioid use disorder are less likely to be labelled with a mental illness.

After adjusting for participant characteristics like age, sex, and race, 40% of respondents labelled the vignette character with prescription opioid use disorder as having a mental illness. In contrast, respondents were significantly more likely to label those with depression (75%), schizophrenia (95%), and alcohol use disorder (66%) as having a mental illness, but less likely to label the vignette character experiencing subclinical distress (29%) with a mental disorder.

Those with prescription opioid use disorder are more likely to be labelled with a physical illness.

Around three-quarters of respondents thought the vignette character with prescription opioid use disorder had a physical illness. This was significantly more than all other conditions including subclinical distress, depression, schizophrenia, and alcohol use disorder.

About half of US residents label prescription opioid use disorder as part of life’s ‘normal ups and downs’.

Approximately half of respondents indicate they thought what the prescription opioid use disorder vignette character was experiencing was part of life’s ‘normal ups and downs’, relative to subclinical distress, and other conditions.

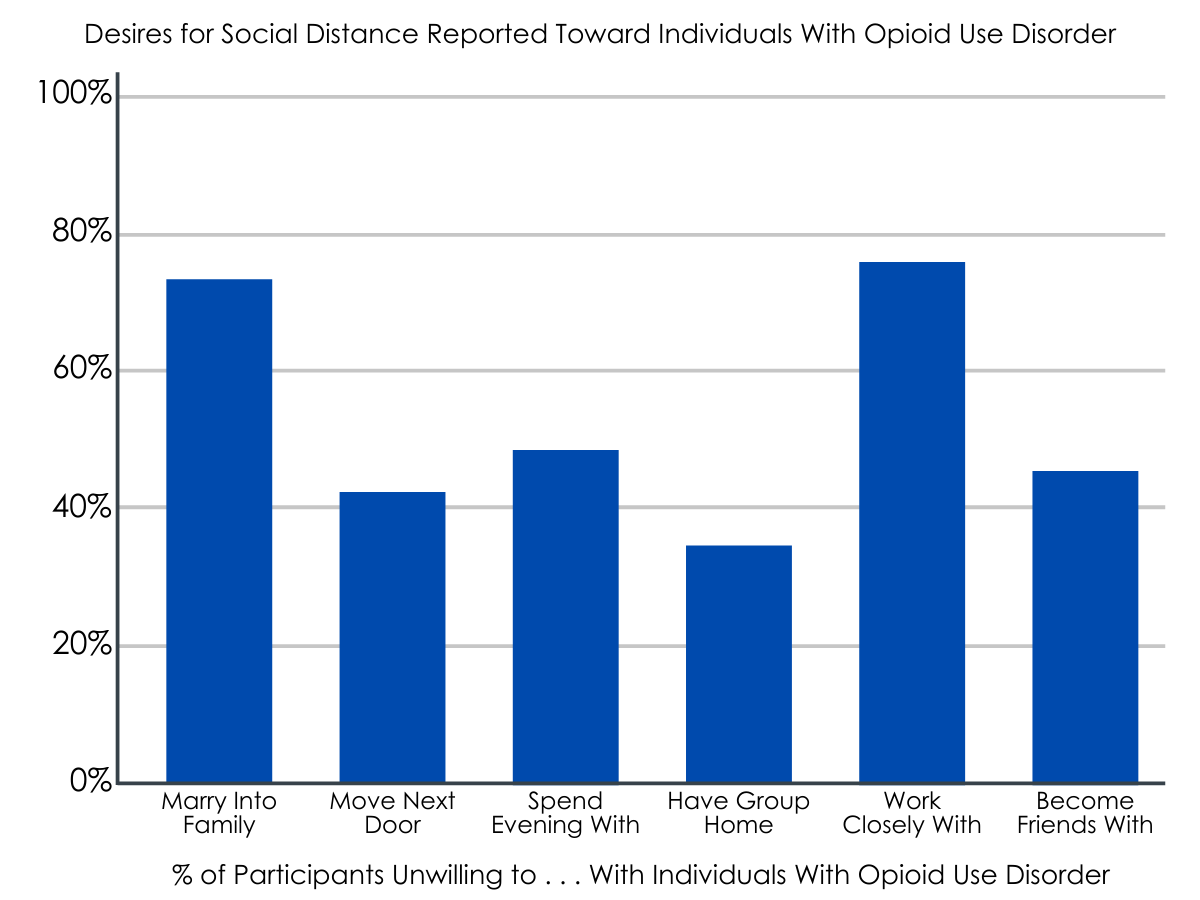

The majority of US residents endorse a desire for social distance from those with prescription opioid use disorder.

When asked about their willingness for social proximity with the vignette character with prescription opioid use disorder, approximately one-third said they would be unwilling to have a group home for such people in their neighborhood, while just under half of respondents were unwilling to have this person move next door to them, were unwilling to spend an evening socializing with such a person or would not become friends with them.

Additionally, around three-quarters of respondents were unwilling to have the person in the vignette marry into their family and said they would not want to work closely with such a person on a job. In comparison, respondents desired significantly less social distance from the vignette characters with depression, and subclinical distress, relative to prescription opioid use disorder. However, desire for social distance from those with prescription opioid use disorder was not significantly different from schizophrenia or alcohol use disorder.

Figure 3.

Individuals with prescription opioid use disorder are seen as a safety risk to themselves and others.

Over half of respondents felt the person in the prescription opioid use disorder vignette was likely to hurt others, relative to only 17% for subclinical distress, and 29% for depression. In contrast, the vignette character with prescription opioid use disorder was perceived as less threatening to others than the vignette characters with schizophrenia, and alcohol use disorder.

Participants viewed the prescription opioid use disorder character as moderately likely to harm themselves relative to the other conditions, more so than those with clinical distress, similar to those with depression and alcohol use disorder, but less than those with schizophrenia.

People with prescription opioid use disorder are seen as less competent to manage their money and make their own treatment decisions compared to those with some disorders, but not others.

Respondents were significantly less likely to perceive the vignette character with prescription opioid use disorder as being capable of managing their own finances relative to a person with subclinical distress, depression, or alcohol use disorder, but more capable of managing their own finances – approximately as much as schizophrenia.

The vignette character with prescription opioid use disorder was also anticipated to have less public trust than the vignette characters with subclinical distress and depression, but more public trust than schizophrenia, and approximately as much as alcohol use disorder.

Respondents were significantly more willing to coerce individuals with prescription opioid use disorder into some kind of treatment than any other condition, including subclinical distress, with the exception of schizophrenia with which there was no significant distinction.

US residents ascribe minimal individual blame for the development of prescription opioid use disorder.

Only 17% of respondents felt that the prescription opioid use disorder vignette character’s condition was caused by their upbringing, compared to 56% for subclinical distress, 43% for depression, 44% for schizophrenia, and 68% for alcohol use disorder.

Additionally, around two-thirds of participants thought the prescription opioid use disorder was probably due to stressful circumstances, relative to other conditions.

With respect to biological factors, only a third of respondents attributed the prescription opioid use disorder to a genetic or inherited problem, compared to 64% for depression, 77% for schizophrenia and 72% for alcohol use disorder. Further, 70% of respondents attributed prescription opioid use disorder to a chemical imbalance in the brain.

Respondents were also significantly less likely to attribute the vignette character’s prescription opioid use disorder to bad character relative to other conditions.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Based on the findings of this study, which can be used to make inferences about the perceptions of the US population, the majority of people in the US believe prescription opioid use disorder is a physical illness, while relatively few think of it as a mental illness. Similarly, endorsement of both biological and environmental causes, as well as bad character, is generally lower for prescription opioid use disorder than for the other conditions explored in this study.

These findings are consistent with previous work that has shown that individuals with opioid use disorder who received opioids from a doctor versus those acquiring opioids illicitly were less stigmatized. These patterns, however, are markedly different from prior results on perceptions of individuals engaged in general drug use, and suggest that people with prescription opioid use disorder are largely conceptualized as having a physical disease for which they are not personally responsible. In other words, those developing an opioid use problem due to a prescription may be viewed more sympathetically compared to those with heroin or other drug use disorders developed through recreational drug use. The type of opioid use disorder from which individuals suffer (licit vs illicit) and/or the origin of their opioid use disorder (prescribed opioids from a medical provider vs obtained illicitly) may influence the degree of stigmatizing attitudes that the general public hold toward such individuals.

It is well appreciated that some individuals in the US developed an opioid use disorder following medically prescribed opioids used to manage pain. The authors’ note that this information, coupled with public beliefs about the addictiveness of medical opioids, probably contributed to low levels of perceived personal responsibility for opioid use disorder for the vignette character, who was described as having developed opioid use disorder after being prescribed opioids for back pain.

Despite lower levels of perceived dangerousness to others in comparison to those with schizophrenia and alcohol use disorder, social rejection of people with prescription opioid use disorder appears high and is on a par with social rejection of those with schizophrenia and alcohol use disorder. The authors note that this may suggest that dangerousness is a less prominent driver of attitudes toward prescription opioid use disorder compared to other severe mental illnesses.

While lower perceived culpability of people who become addicted to opioids via prescription opioids given for pain management is on the whole a good thing, simply deflecting blame to pharmaceutical companies and doctors is not helpful because it may discount the role of additional issues driving substance use disorder in the US including poverty and systemic racism.

Taken together, these findings indicate that prescription opioid use disorder provokes high levels of stigma, even though the majority of Americans don’t blame individuals with prescription opioid use disorder for becoming addicted to opioids when they were prescribed opioids for pain. Further, the US public appears to be pessimistic about their ability to function normally and perform social roles.

There is a pressing need to reframe substance use disorders as the treatable conditions they are. Doing so will invariably reduce the stigma associated with addiction and in turn reduce the massive public health burden of addiction.

- LIMITATIONS

-

As noted by the authors:

- Individuals’ responses were necessarily influenced by the specific information in the vignettes. Respondents’ causal attributions for opioid use disorder might have been different if the vignette had not mentioned that opioid analgesics were initially prescribed by a physician.

- Findings should not be generalized to other forms of non-medical opioid use, such as intravenous heroin use.

Additionally:

- Though the majority of participants endorsed desire for social distance from the vignette character with current prescription opioid use disorder, it is not known if the same individuals would feel the same way about someone in prescription opioid use disorder recovery.

- It is unclear whether respondents may have implicitly associated the original reason for requiring the opioid prescription (i.e., due to the physical illness of back pain) with actual ‘physical illness’, and thus rated to be a physical illness more than the conditions they were asked to consider.

BOTTOM LINE

U.S. residents were significantly more likely to label symptoms of prescription opioid use disorder a physical illness relative to conditions including alcohol use disorder, major depression, schizophrenia, or subclinical distress, and less likely to label opioid use disorder as a mental illness. Notably, opioid use disorder in this specific context was significantly less likely to be attributed to bad character or poor upbringing compared with alcohol use disorder. Nonetheless, perceptions of competence associated with opioid use disorder (e.g., ability to manage money) were lower than alcohol use disorder, depression and subclinical distress. Moreover, willingness to socially exclude people with opioid use disorder was very high, paralleling previous findings for other disorder associated with high levels of stigma (e.g., alcohol use disorder and schizophrenia). Results from this study emphasize the pervasive risk of social rejection faced by people with prescription opioid use disorder, and the complexity of attitudes and beliefs underlying it.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Stigma impedes progress toward reversing the opioid epidemic by discouraging people with opioid use disorder from seeking health and addiction services and increasing secondary harms for those receiving treatment. Coming forward and asking for help in spite of this stigma is one way we can begin to defeat stigma’s harmful effects, and insure more people get help for opioid use disorder. Taking advantage of community supports including harm reduction services, recovery community centers, and mutual-help programs is another way individuals can buffer the harmful effects of opioid use disorder stigma.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Stigma impedes progress toward reversing the opioid epidemic by discouraging people with opioid use disorder from seeking health and addiction services and increasing secondary harm for those receiving treatment. Helping individuals in treatment for opioid use disorder address discrimination can potentially begin to offset some of these harms. Further, social movements that campaign for rights of people who use opioids and humanize these individuals might help to reduce offset stigma.

- For scientists: Stigma impedes progress toward reversing the opioid epidemic by discouraging people with opioid use disorder from seeking health and addiction services and increasing secondary harm. The present findings indicate stigma associated with prescription opioid use disorder is high, even though most people don’t find individuals who developed opioid use disorder as a result of opioid prescription for pain as personally culpable. Studies directly comparing opioid use disorder stigma associated with opioid use disorder arising from prescription opioids for pain, vs. opioid use disorder arising from recreational opioid use are needed to begin teasing out the antecedents of opioid use disorder social stigma.

- For policy makers: Results suggest that public stigma and resulting discrimination will continue to profoundly shape the lives of people with prescription opioid use disorder, adversely affecting physical and mental health and quality of life. This has profound public health implications, because stigma associated with substance use disorder is a significant barrier to health services utilization and recovery. Addressing stigma through public health campaigns and lowering barriers to substance use disorder treatment will be critical for the successful redress of the current opioid overdose crisis. Such public health campaigns might focus on creating an image of persons with opioid use disorder as fighting against a serious condition with real prospect for remission, similar to cancer.

CITATIONS

Perry, B. L., Pescosolido, B. A., & Krendl, A. C. (2020). The unique nature of public stigma toward non-medical prescription opioid use and dependence: A national study. Addiction, 115(12), 2317-2326. DOI: 10.1111/add.15069