What happens when police participate in a public health approach to substance use disorder? Views of an innovative police facilitated referral program in Massachusetts

Drug overdose deaths are at an all-time high, having increased to over 93,000 in 2020, and over 1.5 million arrests are made for drug violations annually. Given the ineffectiveness of criminal justice approaches to substance use disorder, public safety and public health stakeholders are partnering with criminal justice stakeholders to develop innovative programs designed to limit harms and link people with treatment. In this study, researchers examined how five police departments in Massachusetts are implementing police-assisted referral programs for substance use.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

From state-level cannabis legalization to the decriminalization of controlled substances in Oregon, drug policy and views of drugs and people who use them are changing. However, the policing of people who use drugs is often unresponsive to legal reforms. Moreover, policing surrounding drugs disproportionately impacts Black individuals, Indigenous individuals, and people of color. People that identify as Black and Hispanic also suffer greater consequences when arrested for drug and alcohol-related offenses. Moving forward, public safety and public health stakeholders are exploring ways to divert arrest through treatment referrals and reduce the burden of problematic substance use.

Programs like these reflect overarching transitions from a punitive approach encapsulated by the War on Drugs to a public health approach that prioritizes the well-being of individuals with substance use disorder and the communities in which they live. At the same time, most commonly used drugs, such as opioids, cocaine, and amphetamines, remain illegal in most states while the consequences of both substance use, including both legal alcohol use as well as other drug use, reach well beyond the individuals experiencing substance use problems. Thus, a comprehensive public health approach is likely to be most successful if it engages both public safety and public health stakeholders to partner, innovate, and implement change.

In this study, researchers conducted focus groups to explore the implementation and staff perceptions of one evolving strategy: police-assisted referral programs. Police-assisted referral programs have been championed by non-profits and advocacy organizations across the United States such as the nationwide nonprofit Police Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative (PAARI).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a qualitative study based on focus groups and individual interviews to examine how police-assisted referral programs were being implemented and were perceived by program staff. In this study, Davoust and colleagues engaged 5 police departments in Massachusetts that are operating police-assisted referral programs. Focus group and interviews were conducted between June 2019 and March 2020.

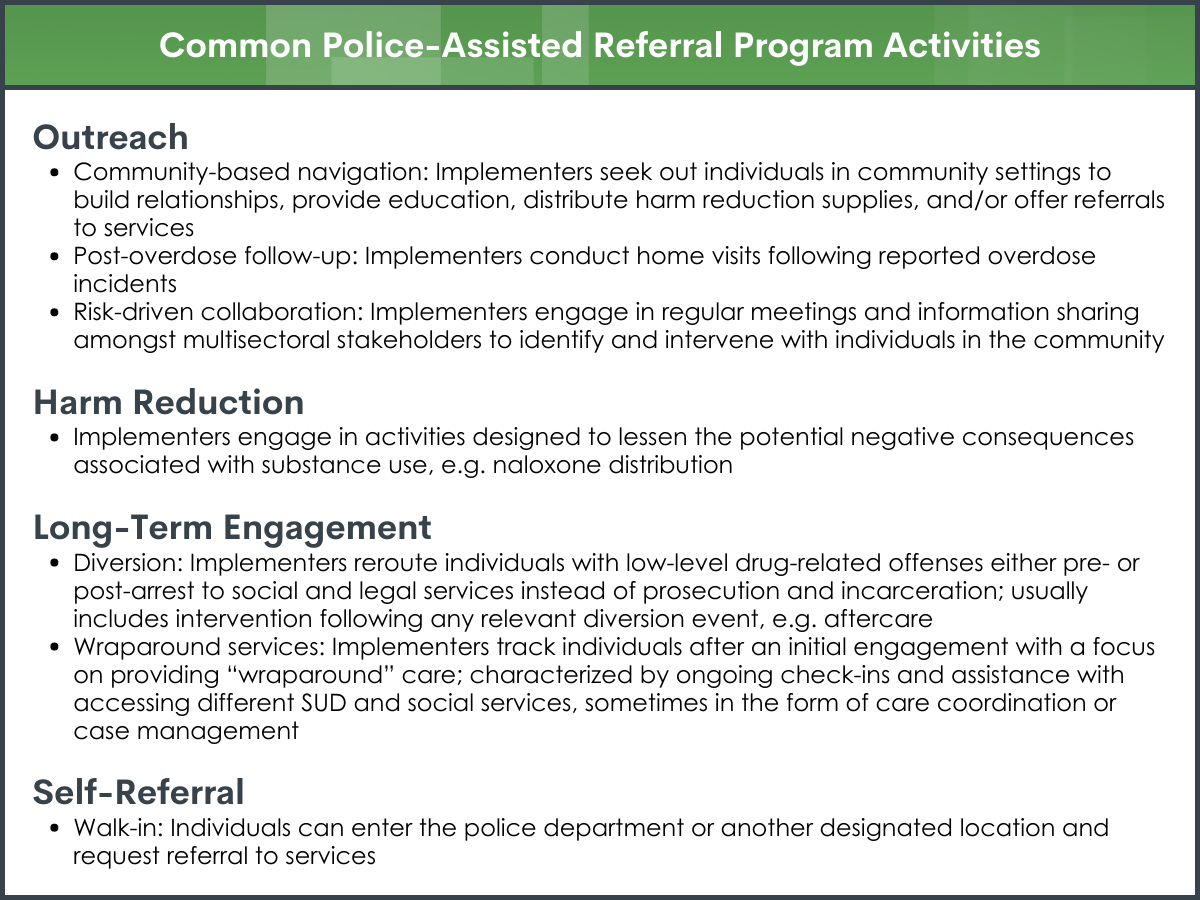

The overarching goal of police-assisted referral programs is to develop non-arrest, or early diversion, programs to help connect people with treatment and recovery support before they enter the criminal justice system. These programs have taken many different forms. However, they often include building relationships between police departments, community-based recovery or mental health organizations, treatment services, and recovery advocates. They also vary in their menus of services. Programmatic aspects have included outreach, harm reduction, long-term engagement, and self-referrals.

The research team conducted 6 focus groups and 4 individual interviews. Focus groups and interviews are forms of qualitative research that help researchers understand how individuals understand a specific phenomenon.

Researchers developed semi-structured guides to help facilitate dialogue surrounding evidence, context, and facilitation of the police-assisted referral programs. The research team recorded each session and had them professionally transcribed. Then, they reviewed those transcripts and assigned categories or codes to words, phrases, and/or paragraphs. Some of the codes they used included acceptability of the program, beliefs about substance use, departmental culture, resources, implementation strategies, and adaptations. After iterative rounds of coding to create a finalized set of codes, multiple team members reviewed the transcripts again to identify underlying patterns. Finally, the research team reviewed the finalized codes and their associated segments of transcript to develop a set of key themes related to program implementation.

To conduct this study, the research team partnered with the Police Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative (PAAPI). This organization formed in 2015 to provide training, strategic guidance, support, and resources to help law enforcement agencies develop non-arrest pathways to treatment and recovery. The nonprofit now encompasses a network of nearly 600 police departments in 34 states and primarily supports non-arrest, or early diversion, programs to help link people to treatment and recovery services prior to entering the criminal justice system.

Focus group participants included 5 police chiefs, 12 police officers, 6 outreach workers, 4 community-based organization (CBO) directors, 2 interns, 1 clinician, 1 program manager, 1 religious representative, and 1 prevention specialist. Although detail on the participants, individual focus groups, and interviews were limited, the team did note that there were 4-9 individuals per community. The 5 communities varied in location, size, and demographics. Two of the communities were urban, one was a small costal town, one was rural, and one was suburban. Two-thirds of one urban community identified as Latinx. Each of the other communities were predominately people identifying as non-Hispanic white. Although not representative at a national level, this does mirror the demographic makeup of Massachusetts. The researchers also indicated that the communities varied in rates of poverty, United States citizenship, and health insurance coverage.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

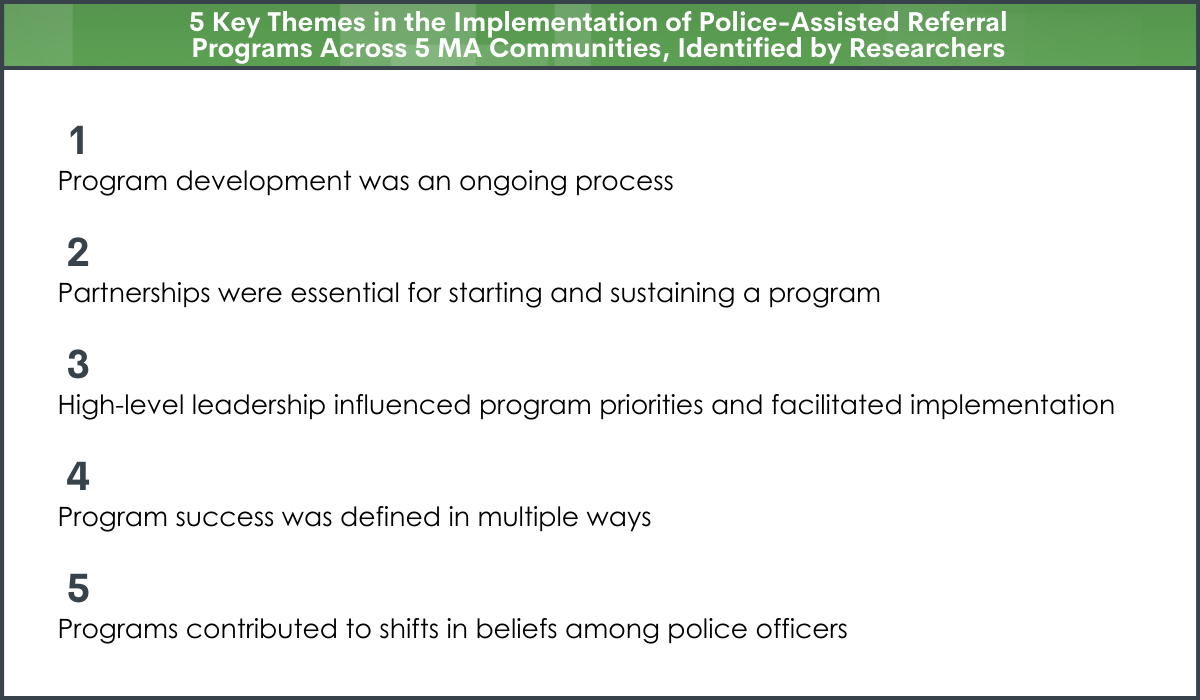

The research team identified five key themes in the implementation of police-assisted referral programs across five communities in Massachusetts.

Program development was an ongoing process.

The researchers found that the five different communities varied in their implementation of referral programs. However, all of the programs shared a focus on increasing access to substance use services for their community. They also exemplified evolving hybrid models. Traditionally, police-assisted referral programs were either direct outreach or self-referral. These programs showed a mix of program activities.

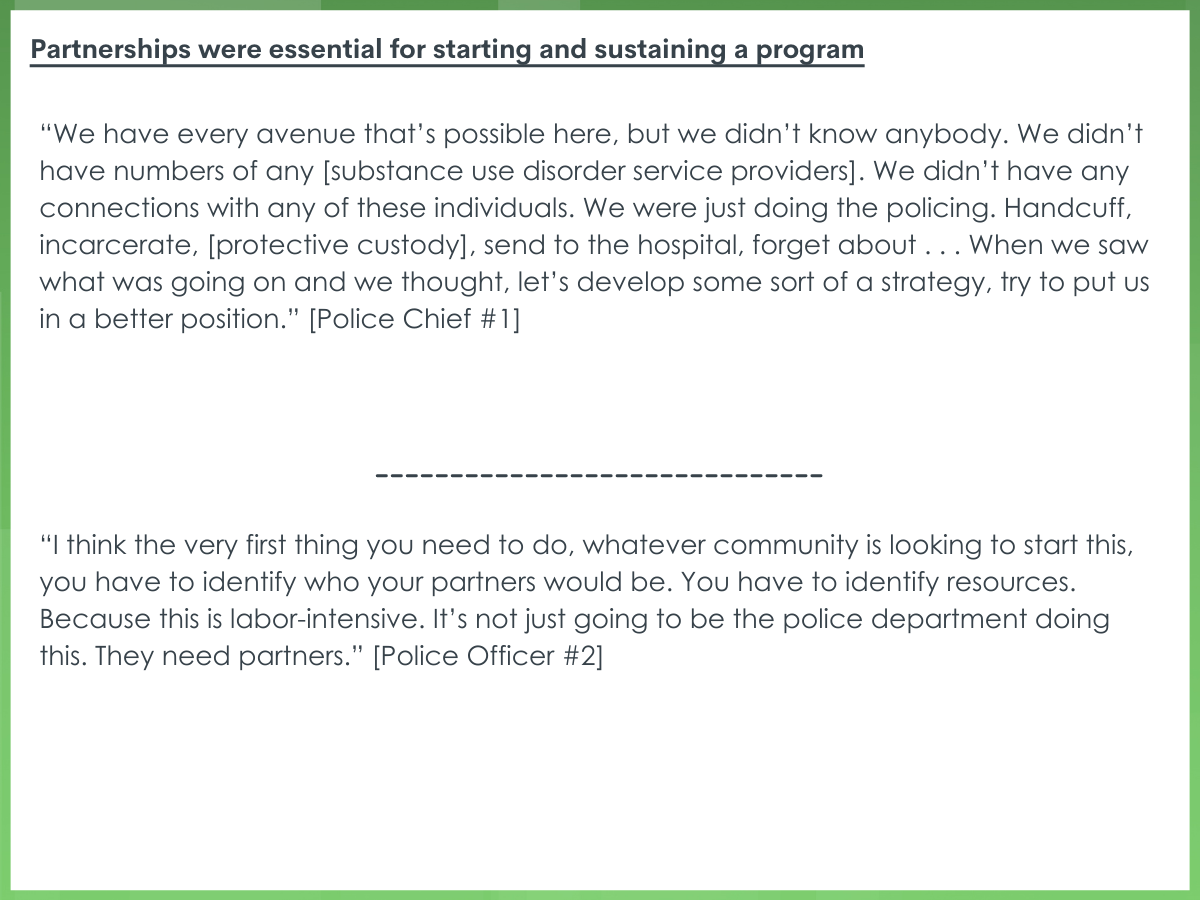

Partnerships were essential for starting and sustaining a program.

“We have every avenue that’s possible here, but we didn’t know anybody. We didn’t have numbers of any [substance use disorder service providers]. We didn’t have any connections with any of these individuals. We were just doing the policing. Handcuff, incarcerate, [protective custody], send to the hospital, forget about . . . When we saw what was going on and we thought, let’s develop some sort of a strategy, try to put us in a better position.” [Police Chief #1]

Participants from each community made it clear that partnerships between police departments and their community were necessary. Partnerships with the police department included other public safety and government agencies, hospital-based health services, outpatient and aftercare programs, health and social service agencies, and community-based organizations. These relationships were vital to move away from siloed approaches of service provision to collaborative arrest diversion and linkage to treatment.

“I think the very first thing you need to do, whatever community is looking to start this, you have to identify who your partners would be. You have to identify resources. Because this is labor-intensive. It’s not just going to be the police department doing this. They need partners.” [Police Officer #2]

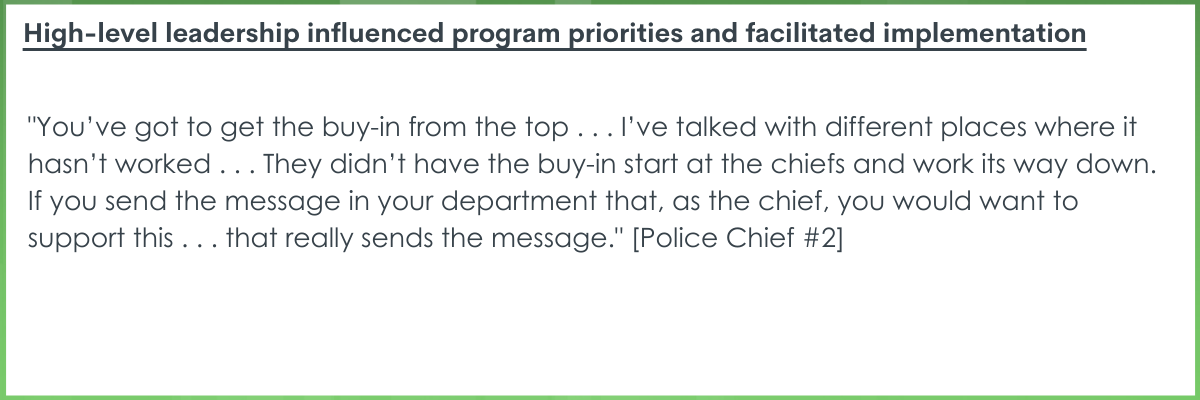

High-level leadership influenced program priorities and facilitated implementation.

“You’ve got to get the buy-in from the top . . . I’ve talked with different places where it hasn’t worked . . . They didn’t have the buy-in start at the chiefs and work its way down. If you send the message in your department that, as the chief, you would want to support this . . . that really sends the message.” [Police Chief #2]

Departmental leadership, particularly the police chief, was reported as fundamental in developing community partnerships. Leadership was identified as both a barrier and a strength. The lack of supportive leadership was seen as a critical barrier. On the flipside, supportive leadership facilitated team cohesion and favorable departmental culture, which reportedly led to successful program implementation.

Program success was defined in multiple ways.

Although all programs echoed the goals of reducing overdose mortality and increasing access to substance use services, some programs identified more immediate and short-term goals. Many programs also defined success beyond individual level outcomes to include gaining community trust, building positive relationships between officers and the community, and shifting attitudes and beliefs of officers regarding substance use. Both individual and community level success emerged through participants expressing the need to “meet people where they’re at”. When formalized treatment was deemed necessary, completing the referral was seen as a measure of success. In other cases, providing resources and building trust in hopes of reducing immediate harm was seen as a success.

“We keep track of where we’re going. Sometimes it’s recovery support services because they’re already engaged in treatment, sometimes it’s family support . . . For those that are still caught up in active addiction, it’s follow-up visits . . . Our goal is to meet people wherever they’re at. So, it might be a harm reduction call. It might be, do you want in-patient treatment, is it appropriate? I think out of habit, we say beds. But it might be medically assisted treatment. We’re open to any and all modalities of treatment. That’s a part of our goal.” [Community-Based Organization Director #2]

Some programs also exhibited different ideas of success based on specific roles. For example, some police officers viewed success as participating in a post-overdose outreach visit and linking that person to an outreach worker. The actual connection to services was viewed as the responsibility of the outreach worker.

“We’re the more tip of the sword kind of guys. We’re just trying to get you through that night when we show up and put some Narcan in you to try to block the receptors, just trying to get you to live through that day . . . Once you get to the hospital, then we hope that through our overdose services, we can get you services down the road where normally maybe you would not. But for the most part . . . That’s where it’s going to come to . . . the outreach services guys that try to get you into the beds . . . Where you can actually do some good, some long-term good.” [Police Officer #5]

Programs contributed to shifts in beliefs among police officers.

“Society’s changing. The whole world realizes that. Incarceration isn’t the answer to addiction, it’s not the answer . . . But we’re changing as society’s changing, because we do mirror our society.” [Police Chief #3]

Participants across roles identified the change in police attitudes and beliefs towards substance use and addiction as one of the most important outcomes of the program. Participants shared how buy-in was initially due to practical benefits, however, program implementation led to substantial changes in the culture of police departments. Police officers began to view addiction as a disease to be treated as opposed to a public safety violation deserving punishment.

“This is not a crime we’re dealing with. We’re dealing with people that do have an earnest problem. And it’s affecting not just them, personally, but it’s affecting their families.” [Police Officer #7]

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

There is an acute need for major reform in policing and public safety in the United States. Although the scope of this problem is beyond this article, the research team highlights a specific topic in much need of reform: policing.

The War on Drugs and its associated policies significantly contribute to arrest and incarceration rates. Police make over 1.5 million drug arrests annually with the vast majority – consistently more than 80% – for possession only. Additionally, 1 in 5 incarcerated people are locked up for a drug offense. People of color are more likely to be stopped, searched, arrested, convicted, and harshly sentenced, for drug violations. In part because of the rising overdose deaths, substance use disorder and other forms of harmful substance use are increasingly being viewed as major public health issues. However, it may be challenging for policy makers to modify long-standing police practices. This necessitates innovative programs and partnerships between public safety and public health stakeholders.

The researchers of this article pinpoint how a police-assisted referral program can change police officers’ attitudes and beliefs about drugs and people who use them. Indeed, previous research has established that beliefs and attitudes impact behavior. However, it has yet to be shown empirically whether police-assisted referral programs like the ones explored in this study promote more compassionate behavior toward individuals with substance use problems, enhanced treatment linkage, and better substance use and health outcomes compared to policing practices as usual.

Program outcomes and views of people who use drugs will be key in the future development of police-assisted referrals. In a study about using 911 calls to trigger post-overdose outreach, people who use drugs reported being afraid to call 911, even in life-saving situations, due to fear of a potential law enforcement response including CPS involvement, arrest, incarceration, and threats to personal reputation and privacy. If people fear calling an emergency line, people may also hesitate to engage directly with police departments. Although study participants indicated building trust within their communities, the experiences and views of people who actively use substances along with people in recovery may prove instrumental in program provision. For example, each of the police departments included in this study had vital partnerships with community organizations that provided expertise in substance use and/or had specialized staff such as recovery coaches employed as outreach workers. Consistent with a recovery-oriented systems of care paradigm, findings from this study highlight not only the potential importance of partnerships, but also the availability and visibility of substance use and recovery services in the community.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The sample only included a subset of implementers of police-assisted referral programs and may not generalize to other police departments.

- The researchers did not collect outcome data and, therefore, any inferences about the effectiveness of these programs on referrals or health outcomes should not be inferred without future longitudinal research.

- The research team did not share detailed demographics about study participants or the communities where these programs were housed. It is therefore difficult to evaluate how well this study captures the full range of individuals or communities that may implement police-assisted referral programs.

- The existing substance use services and organizations within each community was not provided. Differences in program implementation may exist in communities with lower or higher community recovery capital, such as the availability of continuing care services, mutual-aid groups, or recovery community centers.

BOTTOM LINE

This qualitative study found that among five police-assisted substance use referral programs in Massachusetts, programmatic aspects differed but were all aimed at reducing overdose deaths and increasing access to treatment. Police-assisted referral programs may help bridge the divide between public safety and public health stakeholders. These programs facilitated community partnerships and contributed to changing police department culture surrounding views on drugs and addiction. All findings in this study were garnered from the perceptions of staff implementing police-assisted programs. Future research should examine whether these programs improve outcomes of individuals with substance use disorder as intended. If these findings are consistent and in tandem with improved outcomes for people who use drugs, then police-assisted referral programs may be an important strategy for diverting arrests and increasing service utilization.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The researchers from this study highlight how police-assisted referral programs are evolving and may contribute to changing police culture. As both arrest and addiction have major consequences for individuals and families, these referral programs may provide necessary resources to help access treatment and divert arrests. Supporting and being aware of recovery community organizations and police-assisted referral programs may help reshape public safety responses to substance misuse.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Views of drugs and drug users are changing along with evolving drug policy. Many police departments are looking to partner with public health stakeholders, including treatment providers and recovery specialists. Advocating for police-assisted programs may help avert arrest when treatment would be more appropriate. However, evidence from this study suggests many police are unaware of existing supports. Partnering directly with police departments may help advance public health responses to substance use.

- For scientists: The research team reviewed a development in the evolving nature of police-assisted public health approaches and may serve as a foundation for future investigation. Future research in other areas of the U.S. can help determine the generalizability of these finding. Quantitative work examining substance use and other health outcomes of the individuals who participate in these programs in comparison to individuals living in communities that do not implement such programs, can help provide more evidence on their potential utility. In these studies, accounting for the nature of local recovery-oriented systems of care may help to tease apart possible environmental confounders.

- For policy makers: Findings from this study suggest that police-assisted referral programs are viewed positively by police departments and their community partners. We do not yet know how these programs impact people who use drugs. Given the harms caused by criminal justice approaches for individuals with substance use disorder, policies based on public health rather than criminal justice approaches are likely to enhance overall community health. Funding and policy for further investigation into the feasibility and impact of police-assisted referral programs will yield critical knowledge about the utility of these innovative approaches.

CITATIONS

Davoust, M., Grim, V., Hunter, A., Jones, D. K., Rosenbloom, D., Stein, M. D., & Drainoni, M.-L. (2021). Examining the implementation of police-assisted referral programs for substance use disorder services in Massachusetts. International Journal of Drug Policy, 92, 103142.