Psychosocial Therapy & Medication = Double the Benefit?

Psychosocial therapy adds no treatment benefit when used with medication.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Buprenorphine (brand name Suboxone) is a partial agonist that was introduced into the portfolio of treatment options for opioid use disorder 2002. Buprenorphine is used in office-based settings and may allow patients to avoid the stigma associated with opioid maintenance treatment programs and avoid daily attendance.

The provision of psychosocial treatment (or referral) is a mandatory requirement outlined in the Controlled Substances Act for the treatment of opioid dependent patients. Mandatory treatment has the potential to improve pharmacological treatment outcomes, however, at the time of this research, no study had directly compared the effectiveness of multiple behavioral treatment conditions and buprenorphine to a buprenorphine only condition. This study sought to fill this gap.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

After a 2-week induction phase, the authors used a randomized control trial to test the effectiveness of four types of behavioral treatment combined with buprenorphine and medication management.

- MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

Medication management was delivered twice weekly for 18 weeks. Medication management was limited in counseling (consistent with office-based practice settings), and provided by study physicians who used a checklist to address each component such as reviewing the urinalysis results, medication dosage, and adherence to the dosing schedule.

The primary outcome was opioid-negative urine results.

Secondary outcomes included treatment retention, withdrawal symptoms, craving, other drug use, and adverse events.

The four behavioral treatments included: cognitive behavioral therapy (n=53), contingency management which included drawing a prize worth $1-$4 for each negative urine test (n=49), both cognitive behavior therapy and contingency management (n=49), and no additional behavioral treatment (n=51) for a 16-week duration followed by a medication only phase (n=134), and follow-ups at 40 (n=100) and 52 (n=99) weeks.

This sample consisted of opioid dependent patients recruited from an outpatient clinical research center in Los Angeles, California.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The results from this study were surprising to many. Opioid negative test results did not differ across groups at the behavioral treatment phase (weeks 3-18) or any other subsequent time point including medication only (weeks 19-34), or follow-ups at week 40 and 52. In addition, no group differences were found in other measures of opioid use, other drug use including amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, sedatives did not differ between groups for any time point.

A number of other outcomes also showed no difference between groups including withdrawal symptoms, cravings, retention, or domains assessed by the Addiction Severity Index. Although Addiction Severity Index domains and outcomes were not further specified, the Addiction Severity Index includes medical, employment/ support, alcohol, drugs, family/social, legal and psychiatric. Last, there was no difference in adverse events (e.g., constipation, insomnia, sweating/hot flashes, etc.) between groups. Of the 253 adverse events reported, 29.2% occurred in the cognitive behavior therapy group, 24.5% in the contingency management, 24.1% in the cognitive behavior therapy plus contingency management, and 22.1% in the no behavioral treatment group.

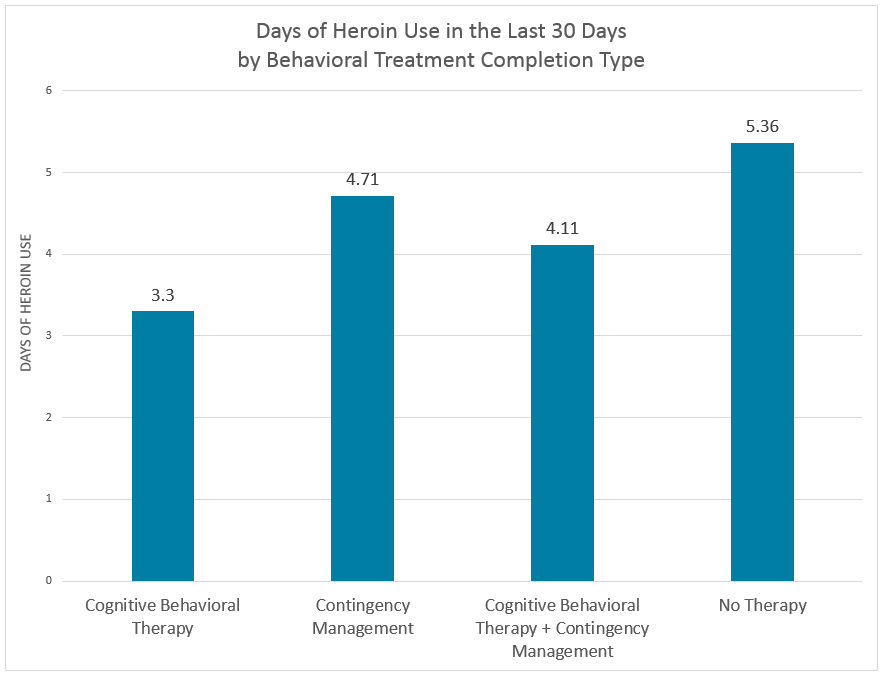

Although no differences were found in opioid use across treatment groups, all groups reported a significant reduction in heroin use in the last 30 days at the end of the behavioral treatment phase compared to baseline.

Note. There is no statistically significant difference between groups but each group showed a significant reduction in heroin use from baseline to the end of behavioral treatment phase.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The results do not suggest that behavioral interventions are useless to patients, but that it is hard to show any benefits of adding specialized behavioral interventions for patients using Suboxone and a simpler “Medication Management” check-up by a prescriber for opioid use disorder in this treatment setting. In prior research, this type of Medication Management intervention has been shown to be as effective when used alone as when added to specialized addiction counseling and this study provided medication management to all groups which may make it difficult to detect the effect of the specialized behavioral addiction treatment because by itself it appears to be as beneficial.

Medication management (also referred to as medical management) is quite intensive in that it required twice weekly appointments for 18 weeks. Thus, it should be considered a legitimate intervention for opioid use disorder in addition to Suboxone that can make patients feel supported, cared about, and from which patients can receive recommendations, referrals, and advice. From a cost-effectiveness perspective, cognitive behavior therapy plus contingency management may require more resources than medication management alone. So if opioid use outcomes are the same then medication management alone may be the best option from a cost-effectiveness perspective.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- By weeks 40 and 52 follow-up samples (n=100) lacked statistical power to detect an effect so negative finding should be interpreted with caution. Lack of statistical power may also be why the percentage of group members who had six or more consecutive opioid-free results did not differ between the group who received cognitive behavior therapy plus continency management (69%) and the group who received no additional behavioral therapy (59%).

- Comparison between the 2,002 participants who made it through screening and induction with the 164 who were not randomized showed that the non-randomized group reported more mean days of heroin use (15.3 versus 22.5) and had a higher percentage of opioid-positive tests (80.2 versus 90.7) which suggests the sample may be somewhat less severe than treatment seeking patients in real-world clinical settings.

- The medication management in this study might not be representative of that offered in real world clinical settings, few clinicians see patients twice weekly for 18 weeks. It is uncertain how the results of this study will translate to real world treatment settings that do not offer a similar maintenance structure.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: This study found no evidence that cognitive behavior therapy and contingency management reduce opioid use when added to Suboxone and a twice weekly Medical Management intervention in opioid use disorder patients seeking treatment. Still, 60% of the patients felt their psychosocial treatment was effective in treating their opioid use disorder. Individual patient preferences may play a role in determining how desirable psychosocial treatment is when added to medication for opioid use disorder.

- For scientists: The Controlled Substance Act requires ancillary behavioral treatment when using pharmacotherapy to treat patients with opioid use disorder, however, this study found no evidence that addiction specific counseling adds any benefit to the effects of medication and Medical Management interventions.

- For policy makers: Despite federal guidelines that require ancillary treatment or referral to behavioral treatment as found in the Controlled Substance Act for the treatment of patients with opioid use disorder, this study compared three psychosocial therapies to a no therapy group (i.e., medication alone) and offered no evidence to suggest any added benefit in terms of reduced opioid use, cravings, withdrawal, or increased treatment retention. However, the Medical Management intervention did involve physician counseling twice weekly for 18 weeks, and this all occurred within the context of a clinical trial. Many clinicians do not provide this intensity of monitoring and counseling, a known therapeutic benefit from being assessed and contacted frequently within the context of a research study.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study found that the addition of a specialized addiction behavioral treatment component (i.e., cognitive behavior therapy, contingency management, and cognitive behavior therapy plus contingency management) to Suboxone maintenance did not decrease opioid use, other drug use, withdrawal symptoms, cravings or increase retention when compared to a group that received no specialized addiction-specific behavioral treatment (i.e., medication plus a structured Medication Management protocol). Suboxone plus frequent checkups and monitoring that this type of Medication Management intervention provides appears to offer the same results in terms of opioid use outcomes that addiction specific behavioral counseling does. Thus, offering this type of protocol with Suboxone may be an option that is likely to be effective and may prove to be more cost-effective.

CITATIONS

Ling, W., Hillhouse, M., Ang, A., Jenkins, J., & Fahey, J. (2013). Comparison of behavioral treatment conditions in buprenorphine maintenance. Addiction, 108, 1788-1798.