Public stigma of opioid addiction

Public stigma of opioid addiction can impact service availability and access, as well affected individuals’ mental health and well-being. This study reports on the public’s attitudes toward opioid addiction from a statewide survey in Pennsylvania with an eye toward improving public health approaches.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Stigma related to opioid addiction encompasses the policies and practices, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination that result in the unjust social devaluation and status loss of people with opioid addiction. This can manifest in several ways. First, stigma may take the form of public policies that criminalize people who use substances, such as President Nixon’s declaration of the “war on drugs,” which rests on the theory that drug use is voluntary and controllable and can therefore be stopped through harsh punishment. They may also manifest as stereotypes characterizing people with substance use disorders as dangerous, unpredictable, or untrustworthy. Stigma may also manifest as prejudice or emotional reactions of contempt, blame or moral outrage toward people with substance use disorders. They can also result in actions, such as discrimination or unfair behaviors that are demeaning, condescending, or rejecting towards people with substance use disorders. Indeed, people in recovery from opioid use disorders report receiving poor or cold treatment from healthcare providers, being fired or not hired by employers, and being socially rejected or distrusted by family members and friends.

Unsurprisingly, stigma has negative effects on the mental health and well-being of people with opioid use disorder. Discrimination is associated with depression, anxiety, decreased quality of life, lower recovery self-efficacy, and lower self-esteem among people with substance use disorders, which may in turn relate to in increased substance use as a form of distraction coping. Stigma also may influence people to delay healthcare, avoid disclosing drug or use or downplay pain to medical staff, or request to be discharged against medical advice.

Less than half of people being treated for opioid use disorder receive medication treatment through a substance use treatment program, which some theorize may have roots in stigma towards individuals themselves (e.g., deserving of punishment). For example, clinicians and patients have labeled medications for opioid use disorder as “another way to get high.” Furthermore, addiction treatment continues to be siloed from the rest of the healthcare system, which perpetuates the message that a substance use disorder is not the same as a chronic health condition like diabetes. Stigmatizing beliefs related to recovery, including the false belief that willpower should be enough to quit substance use, may also impact public resistance to information supporting treatment over criminalization.

Reducing public stigma related to opioid addiction is key to a comprehensive effort to increase availability, access, and engagement in professional treatment as well as community-based recovery support and harm reduction services. In this study, researchers surveyed a representative sample of adults in Pennsylvania about their stigmatizing attitudes related to opioid addiction. In order to focus efforts to reduce opioid addiction stigma, research that aims to understand public stigma can help identify potential intervention points.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

In June-July 2020, the researchers surveyed a statewide representative sample of adults living in Pennsylvania (N = 1033) about their level of agreement or disagreement with statements representing stigmatizing attitudes, beliefs, and their willingness to engage with people with opioid addiction.

Participants were recruited using an online survey response pool company that maintains a nationally representative sample of adults for research purposes. Participants were at least 18 years of age and residing in Pennsylvania. The researchers used a quota-based system to balance the sample of survey respondents on sex, age, and region. Before performing any analyses, participants were weighted to make the sample representative of the Pennsylvania population based on race, ethnicity, educational attainment, living in an urban or rural area, and Pennsylvania department of public health region. That way, if the sample had more representation from one group than another, the weighting process gives more weight to participants who are underrepresented and less weight to participants who are overrepresented, effectively evening out the sample characteristics to more accurately represent the prevalence in the state population.

Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement or disagreement with questionnaire items that covered general attitudes about people with opioid addiction, social exclusion of people with opioid addiction, and perceptions on the effectiveness of treatments for opioid use disorder. The questionnaire items were developed by the team of addiction researchers because at the time of the study no comprehensive measure of public stigma associated with opioid addiction existed. The researchers reviewed questionnaires focused on substance use stigma and stigma in other areas, such as severe mental illness, and adapted those items to focus on stigma associated with opioid addiction.

After balancing the sample on population characteristics using the statistical weighting procedure, the researchers report the proportion of the sample who agreed or disagreed with each statement. Response options “strongly agree” and “agree” were collapsed into “agree” and the same was done with disagree responses. The researchers also reported the percentage of participants who selected “neither agree nor disagree” and “unsure/prefer not to answer” for each item. Then researchers tested if there were differences in how participants responded by group characteristics including, sex (male or female), age (18-34, 35-64, 65 and older), race (White, nonwhite), and urban/rural status (urban or rural).

Participants were on average 48 years old and half of the sample were women (52%). In terms of race and ethnicity, a majority of the sample was non-Hispanic White (85.5%), 5% of participants were non-Hispanic Black, 4.4% were Hispanic or Latinx, and 4.9% were Asian, American Indian or Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Pennsylvanians endorsed generally non-stigmatizing attitudes towards opioid addiction.

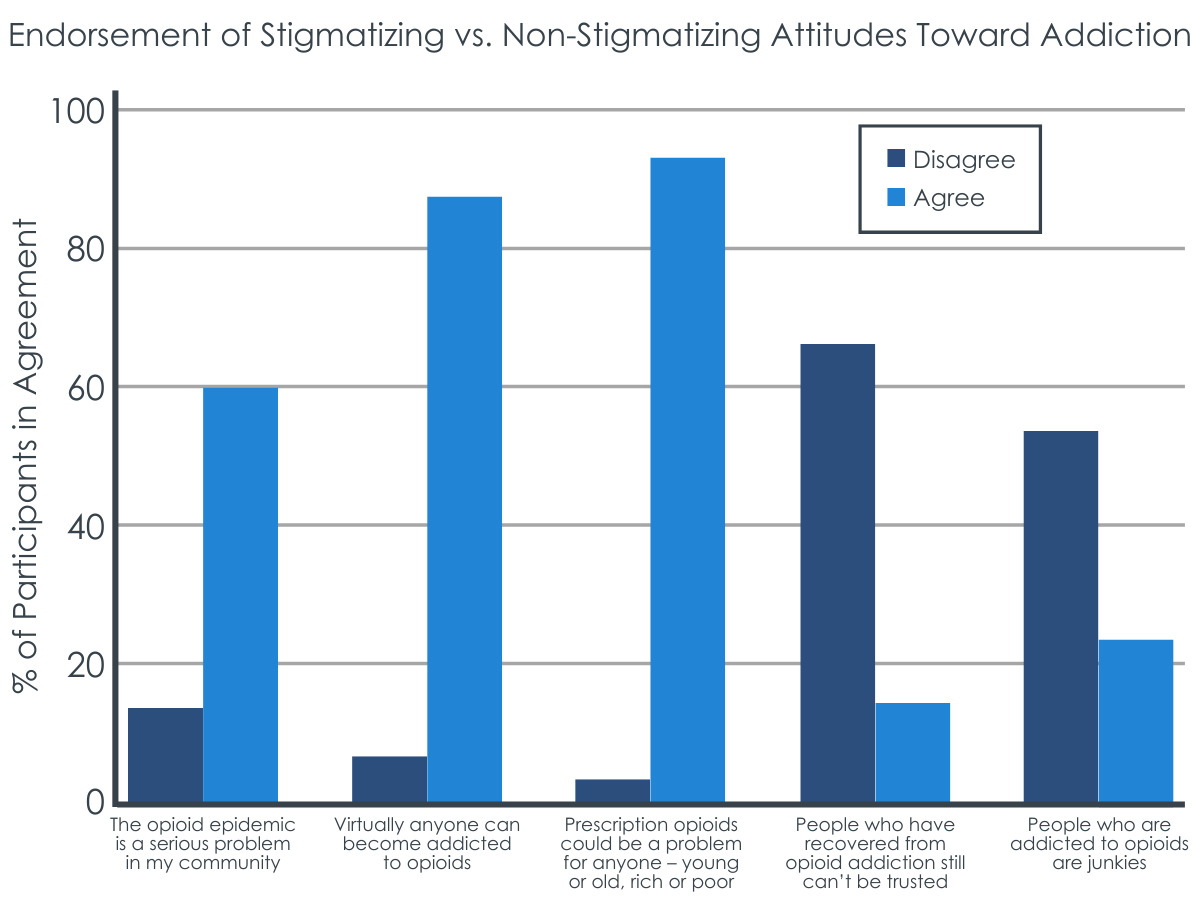

60% of participants agreed that “the opioid epidemic is a serious problem in my community,” 87% of participants agreed that “virtually anyone can become addicted to opioids,” 93% agreed that “prescription opioids could be a problem for anyone – young or old, rich or poor,” 64% disagreed that “people who have recovered from opioid addiction still can’t be trusted” and only 23% agreed that “people who are addicted to opioids are junkies.”

Attitudes varied on opioid addiction as a medical illness or “moral failing”.

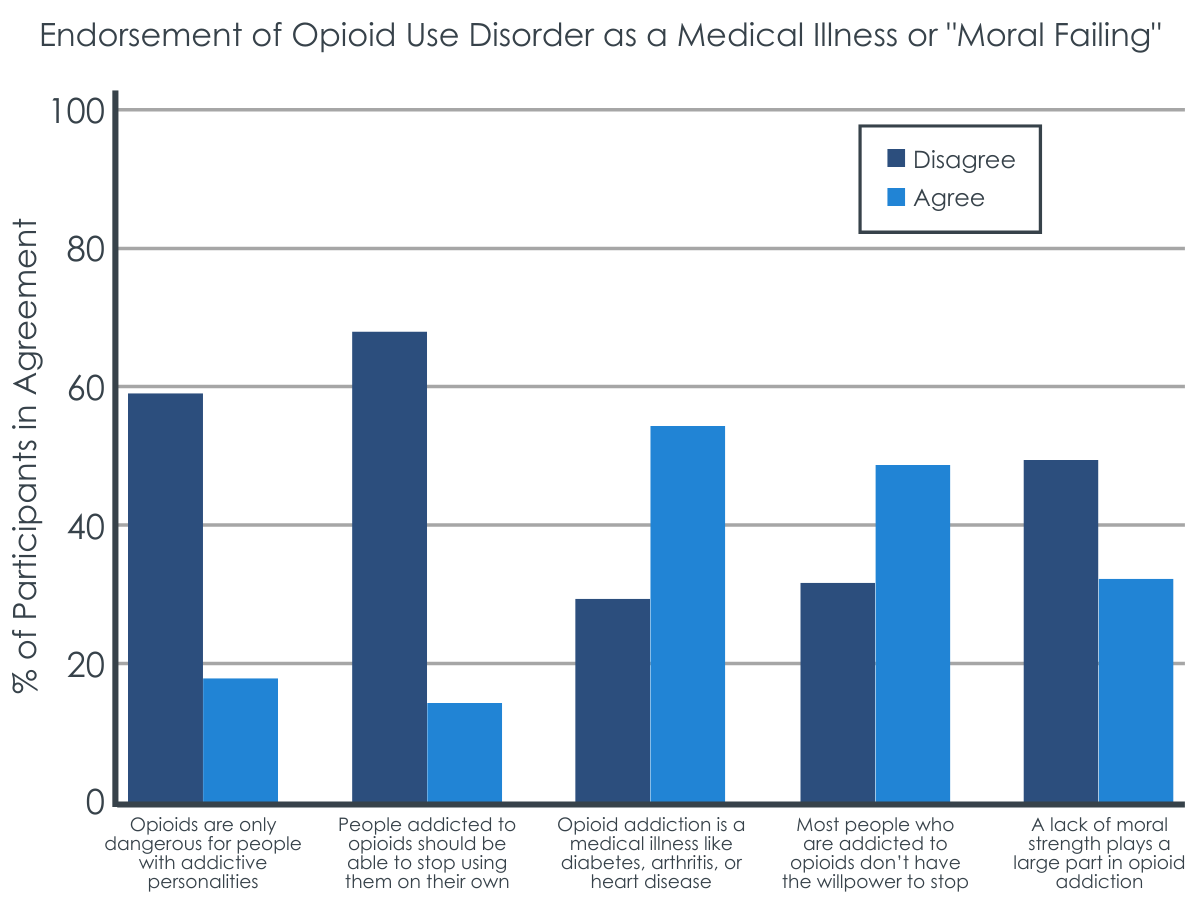

Almost 60% disagreed that “opioids are only dangerous for people with addictive personalities” and 66% disagreed that “people addicted to opioids should be able to stop using them on their own.” Only 56% agreed that “opioid addiction is a medical illness like diabetes, arthritis, or heart disease,” while 30% disagreed. 48% agreed that “most people who are addicted to opioids don’t have the willpower to stop,” while 31% disagreed. Almost 50% disagreed that “a lack of moral strength plays a large part in opioid addiction,” while 32% agreed.

Pennsylvanians were ambivalent in their willingness to socialize with people with opioid use disorder.

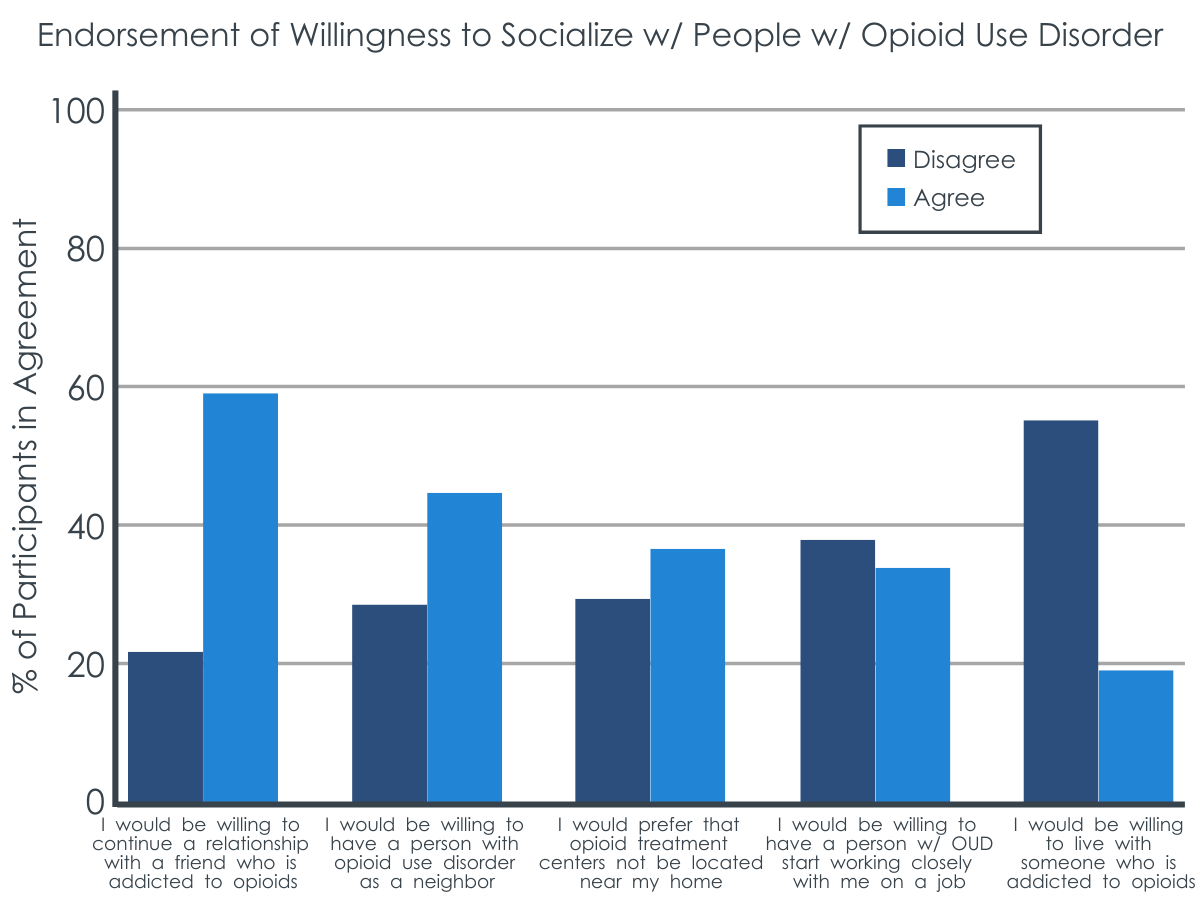

Almost 60% agreed they would be willing to continue a relationship with a friend who is addicted to opioids. Only 43% agreed they would be willing to have a person with opioid use disorder as a neighbor. 37% agreed they would prefer that opioid treatment centers not be locations near their home. Only 34% agreed they would be willing to have a person with opioid use disorder start working closely with them on a job, and only 19% agreed they would be willing to live with someone who is addicted to opioids, while 57% disagreed.

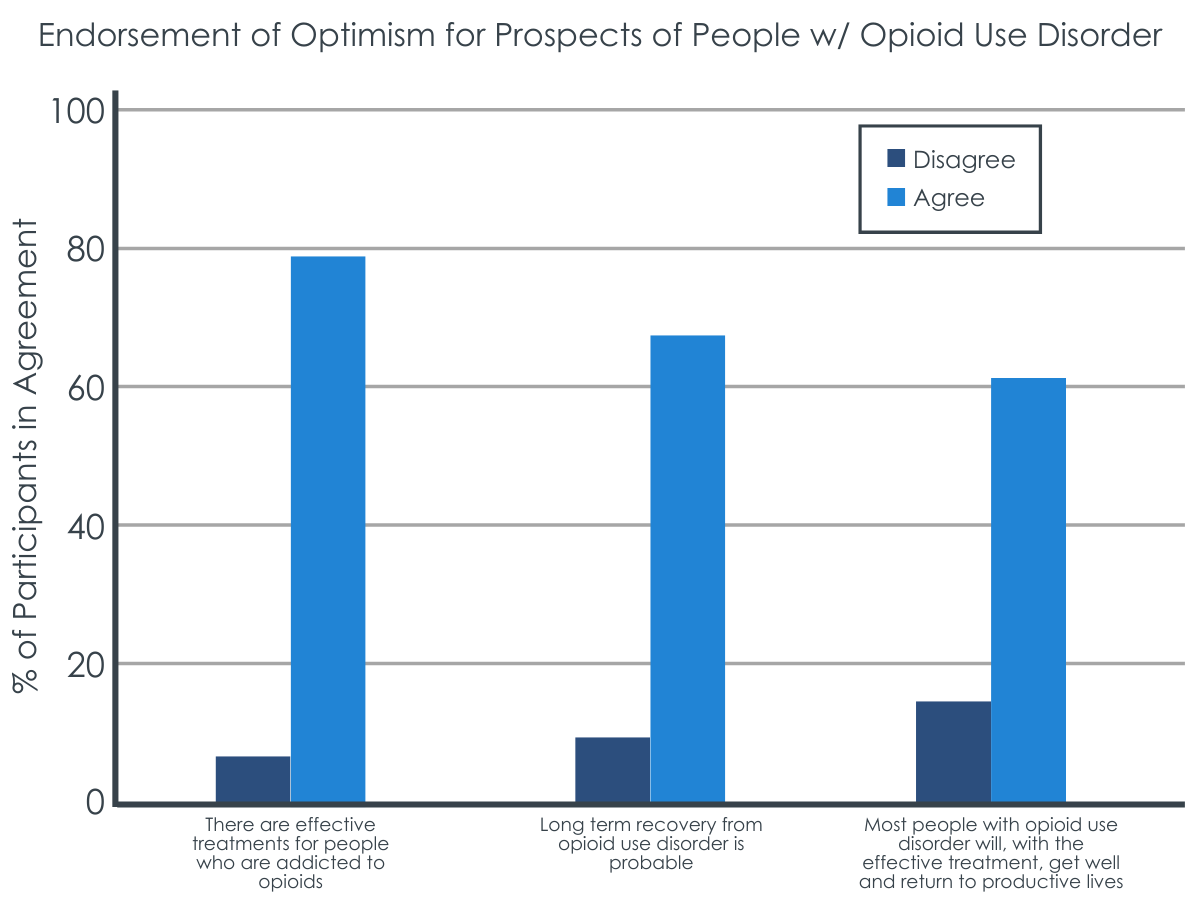

Attitudes were generally optimistic about the prospects of individuals with opioid addiction.

79% agreed “there are effective treatments for people who are addicted to opioids.” 68% agreed that “long term recovery from opioid use disorder is probable,” and 61% agreed that “most people with opioid use disorder will, with the effective treatment, get well and return to productive lives.”

Stigmatizing attitudes were fairly consistent across groups (sex, age group, race, or urban vs rural setting).

There were no differences by race or urban versus rural setting across all public stigma items. Men endorsed somewhat more stigmatizing attitudes about opioid addiction generally and slightly more stigmatizing attitudes about treatment compared to women, whereas women endorsed slightly more social exclusion items than men. Individuals 65 and older endorsed more stigmatizing behavior toward individuals with opioid use disorder than younger individuals ages 18-35.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

While a substantial majority of the Pennsylvania public endorsed generally non-stigmatizing beliefs about people with opioid addiction, and agreed that long-term recovery is possible, responses were much more mixed when the public was asked about their willingness to live or work with a person with a current opioid addiction. This suggests that participants may have been more likely to rate questions in a socially desirable direction when the item was more apparently measuring prejudicial beliefs or stereotypes about people with opioid addiction (e.g., 64% disagreed with “People who have recovered from opioid addiction still can’t be trusted” and only 23% agreed with “People who are addicted to opioids are junkies”). However, when questions focused on social exclusion that more subtly measured potential discrimination, the public opinion showed more ambivalence about social integration of people with opioid addiction.

This is particularly important because these items represent the public’s attitudes about where people with opioid addiction should live, work, and receive healthcare – areas heavily influenced by public policy decisions. For example, legally sanctioned policies under the Fair Housing law allow housing agencies to deny services for people engaging in active drug use or have histories of drug use. In neighborhoods, local substance use disorder treatment centers and harm reduction efforts have been opposed via protest, petition and harassment of people who use drugs. So, while the public may endorse non-stigmatizing attitudes towards people with opioid addiction, if the public opposes policy that supports healthcare access for people with opioid addiction, this maintains stigma at the systemic level and is reflective of “not in my back yard” (NIMBY) politics.

The Pennsylvania public was also mixed about whether opioid addiction was a medical illness, a lack of willpower, or a moral failing. Given that addiction treatment continues to be siloed from the rest of the health care system and even from some mental health systems, it is perhaps not surprising that the public was more ambivalent about opioid addiction being a medical illness like diabetes, arthritis, or heart disease. However, the NIH describes drug addiction as a “chronic relapsing brain disease” strongly advocating for its medical impact and nature, and not a lack of will power or moral failing. Some early research on integrated primary care settings, where behavioral health is imbedded within general medical practice, shows promise to help reduce mental health stigma, however further research is needed to show consistent stigma reductions. Furthermore, little to no research has focused on whether behavioral health integrated within primary care could also reduce substance use disorder stigma.

It’s notable that the questionnaire items the researchers developed for this study focused on prescription opioid use, referred to opioid addiction broadly, or referred to opioid use disorder specifically, but not ‘heroin use’ or ‘injection drug use.’ Research suggests that specific language used to refer to addiction and substance use can influence participant responses. For example, in a study comparing terms like “substance abuser” versus “having a substance use disorder,” participants had more stigmatizing ratings when “substance abuser” was used to describe a person “actively using drugs and alcohol” than when describing the person as “having a substance use disorder.” Similarly, the public shows more favorable attitudes towards supervised consumption sites when they are referred to as ‘overdose prevention sites’ rather than ‘safe consumption sites’. Furthermore, language meant to decrease stigma may in fact increase stigmatizing attitudes, depending on the context. For example, referring to opioid addiction as a “chronic relapsing brain disease” has shown to reduce public blame, but also reduced public optimism for a person’s likelihood to recover. On the other hand, when opioid use was referred to as a “problem,” public blame was highest, but was also rated most highly for likelihood to recover. If reducing stigma is the goal, then the best term to use may vary depending on the context.

Additionally, people with opioid use disorder who use heroin or engage in injection drug use may experience more stigma than people with a “prescription” opioid use disorder. Similarly, in a study comparing public stigma of different mental health and substance use disorders, participants were more likely to label prescription opioid use disorder as a physical illness and less likely to label it a mental illness compared to alcohol use disorder. The researchers used ‘opioid addiction’ and ‘opioid use disorder’ on the survey interchangeably, which could have affected the public’s agreement with stigmatizing attitudes in unknown ways. Additionally, we don’t know how the public’s ratings would have changed if more items referred to “heroin” or “injection drug use,” specifically.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Questionnaire items in this study used the terms ‘opioid addiction’ and ‘opioid use disorder’ interchangeably, which could have affected participants responding in unknown ways. As discussed above, multiple research studies show that language matters because it influences public attitudes about addiction. For example, the public had more favorable attitudes towards supervised consumption sites when they were referred to as ‘overdose prevention sites’ rather than ‘safe consumption sites’. Terms to refer to opioid addiction may have differed across items in the survey because of the way the researchers developed the questionnaire. The researchers noted that some items were adapted from questionnaires focused on other related areas, like mental illness stigma, whereas others were copied exactly from existing scales. Given this, we don’t know how participants may have responded and how their ratings would have changed if all items referred to ‘opioid use disorder’ or ‘opioid addiction’ consistently across the questionnaire.

- The study was conducted in among the Pennsylvania public; it is unclear how typical the results found here will generalize to other states or to the country as a whole.

- The researchers used a questionnaire developed by their team, meaning the questionnaire had not been previously tested for its psychometric properties. Psychometric testing is important to know if a questionnaire is actually measuring what we think it’s measuring, and if it’s measuring it consistently over time. For example, a measure would not be very useful if participants interpreted the questions differently from how the researchers intended. At the time of the study, there was no comprehensive measure of opioid addiction stigma, which is why the researchers chose to create one themselves. However, it means that we can’t confidently say that this questionnaire validly and reliably measures public stigma.

- The researchers did not report how many participants in the sample had experience with opioid use or addiction. It would be useful to know how many participants in the sample had personal experience with opioid use, substance use disorder, or known someone with a substance use problem, as this may also influence stigmatizing attitudes. It’s possible the researchers measured this and did not report it for this manuscript.

- The researchers asked participants about the effectiveness of specific medications for opioid use disorder, such as “buprenorphine” and “methadone.” Participants frequently rated these items as “unsure/prefer not to answer.” The researchers may have gathered more useful information if they had asked about ‘medications for opioid use disorder’ generally.

BOTTOM LINE

This study found that, among a representative sample of 1,033 adults residing in Pennsylvania in June-July 2020, public stigma of opioid addiction was common, especially related to social exclusion of people with opioid addiction. While the Pennsylvania public agreed that virtually anyone could become addicted to opioids and that long-term recovery was possible, there was no clear consensus about whether they considered opioid addiction a medical illness, a lack of willpower, or a moral failing.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Public stigma towards people with opioid addiction can discourage people from engaging in treatment and contribute to worse mental health. People with opioid addiction can also experience stigma from family and loved ones, which can be internalized and contribute to shame. If society, families, and loved ones worked towards understanding addiction like a medical illness, rather than a problem of self-will or a moral failing, people with addiction may experience fewer mental health symptoms as a result of stigma and be more motivated to engage in treatment.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Public stigma towards people with opioid addiction can discourage people from engaging in treatment and contribute to worse mental health. If society worked towards normalizing addiction treatment, similar to treatments for other chronic illnesses with biological, psychological, and social-environmental components, people with addiction may be more motivated to engage in treatment, have better treatment experiences, and experience fewer mental health symptoms as a result of stigma.

- For scientists: Findings from this 2020 statewide representative survey of adults in Pennsylvania show that although public stigma related to opioid addiction was not common on items describing general attitudes, responses were mixed on items relating to social exclusion and whether opioid addiction was like a medical illness. The study used a researcher developed questionnaire not psychometrically validated, in which items used terms ‘opioid addiction’ and ‘opioid use disorder’ interchangeably. Additionally, items largely focused on prescription opioids and did not mention heroin or injection drug use. No data were reported on participants familiarity with opioid addiction, which may have also influenced responses. Future studies should use psychometrically validated measures of stigma, attend to, and be specific about, language used in the measures as this could influence stigma ratings, and include information about respondents’ proximity and familiarity to substance use disorders.

- For policy makers: Public stigma was most prevalent when participants were asked about their willingness to live or work with a person with opioid addiction. These areas are especially important for public policy because often public policy dictates where addiction treatment centers can be located, workplace protections (or lack thereof) for people with substance use disorders, and housing regulations. Lack of protections or access to treatment can contribute to worse overall well-being for a person with addiction. Ensuring people with opioid addiction have legal protections in society could contribute to the overall well-being of people with substance use disorders and facilitate access and engagement with treatment.

CITATIONS

Kaynak, Ö., Whipple, C. R., Bonnevie, E., Grossman, J. A., Saylor, E. M., Stefanko, M., . . . & Kensinger, W. S. (2022). The Opioid Epidemic and the State of Stigma: A Pennsylvania Statewide Survey. Substance Use & Misuse, 57(7), 1-11. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2022.2064506