Quitting Cigarettes in Addiction Treatment?

Some think that it is too risky to quit smoking cigarettes during treatment for alcohol and other drug use disorder. Might smoking abstinence actually be a good thing for recovery when addressed at the same time that a person’s alcohol or other drug use is addressed?

Does providing rewards for smoking abstinence make a difference to smoking outcomes, or to drinking and other drug use?

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Cigarette and other tobacco smoking are very common among individuals with alcohol and other drug use disorders. For example, estimates in the early to mid 2000s show that 75% of individuals with alcohol use disorder smoke cigarettes, compared to only 21% of adults more generally at this time (which has decreased to 17% more recently). Research suggests half of those with alcohol use disorder will eventually die from smoking-related illness.

A question is often raised, therefore, about when is the optimal time to address tobacco cessation. Should it be addressed at the same time as addressing other alcohol/drug use disorders or perhaps at a later time point once the person is in early or sustained remission from their alcohol/drug use disorder?

Some people want to quit at the same time and some may wish to quit at a later time. For people who would like quite cigarettes at the same time as their alcohol/drug use, several groups have developed and tested interventions to help individuals quit cigarette smoking during alcohol use disorder treatment. In general, however, these treatments have had limited success compared to treatments delivered in community settings.

That said there is some evidence that shows that trying to quit cigarettes while in treatment does not appear to be harmful to individuals’ alcohol/drug recovery attempts either. An example of the challenges incorporating smoking cessation into addiction treatment is illustrated by this study summarized in a prior issue of the Recovery Bulletin, where a maximum of only 8% of participants were smoking abstinent (for 7+ days) in the best treatment over several points in time.

In the present study, Cooney and colleagues tested whether adding motivational incentives, often referred to as “contingency management”, to a typical smoking cessation intervention improves smoking outcomes among individuals in addiction treatment. As outlined in this prior Recovery Bulletin, for example, contingency management is an approach that provides rewards for healthy behavior (e.g., abstinence), and is among the most helpful strategies to reduce alcohol and other drug use – at least while those contingencies are in place.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study examined 83 individuals with alcohol use disorder attending a 3-week Intensive Outpatient Program for substance use disorder in the Veterans Administration (VA) and who also had a desire to stop smoking and to enroll in the VA’s smoking cessation program.

They were randomized to one of two smoking cessation interventions:

- Smoking cessation as usual, including cognitive behavioral therapy and 8-week nicotine replacement therapy (a nicotine patch; n = 41)

- The same intervention but with contingency management for smoking abstinence added (n = 42).

The contingency management condition rewarded smoking abstinence beginning with day 5, and increasing with each consecutive day of abstinence, allowing for a maximum total earned of $140 over 8 days. The smoking interventions lasted 120 minutes total, with the contingency management group getting 12 daily 10-minute sessions and the smoking cessation-as-usual group getting three 40-minute sessions. The substance use disorder treatment program consisted of daily treatment for 5 hours per day, including cognitive-behavioral, motivational enhancement, and 12-step facilitation approaches.

Groups were compared on smoking abstinence across 7 days (i.e., “7-day point prevalence”) at the end of the smoking cessation intervention (about 12 days after their target quit date), and at 1-month and 6-month follow-ups (i.e., 1 and 6 months after their target quit date). Smoking was measured by self-report and validated by carbon monoxide level, a common biochemical verification of smoking. Alcohol and other drug abstinence was measured as complete abstinence from their smoking quit date to the end of the smoking cessation intervention, and complete abstinence at 1-month covered the 30 days after their quit date, and at 6-months the 30 days leading to that follow-up.

Authors not only investigated differences between the contingency management and smoking cessation-as-usual interventions, but also whether there were any group differences on alcohol and other drug outcomes, measured by breathalyzer and urine toxicology screens, respectively. They predicted that the contingency management group would have better smoking abstinence rates, as well as better alcohol and other drug outcomes.

In addition, they examined any group differences in the time it took to relapse for cigarette smoking, defined as 7 straight days of smoking or weekly or greater smoking for 2 consecutive weeks.

- PARTICIPANT DEMOGRAPHICS

-

- Study participants were 96% male (which is not uncommon in VA samples), 67% White, and 39% homeless.

- They were 50 years old on average. About half also met criteria for another drug use disorder (in addition to alcohol), and their average Fagerstrom nicotine dependence score was 5.2 (SD = 1.9) on a 0 to 10 scale (The Fagerstrom score is a common method to measure physical dependence on nicotine, and in this sample, average score was on the border between moderate and high dependence).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

First, it is important to note that the groups used a similar number of nicotine patches during the 6 month study period (32 for the contingency management and 26 for the smoking cessation as usual group); so they received a similar dose of nicotine replacement therapy.

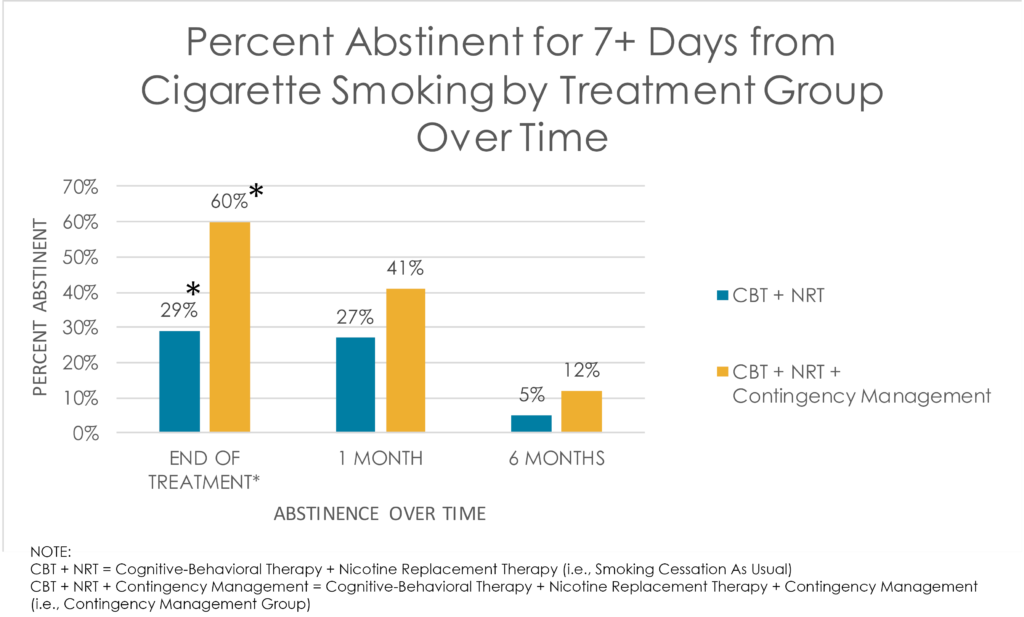

Consistent with the authors’ predictions, the contingency management group had much greater rates of abstinence at the end of the smoking cessation intervention (60% vs. 20%, a statistically significant difference).

There were slight differences at 1- and 6-month follow-ups after the rewards were no longer given for abstinence, in other words after the contingencies were removed, but these differences were not statistically significant (i.e., the difference was not sufficiently large enough to establish it is was unlikely to have occurred by chance).

Overall, across both groups, 35% of participants were abstinent from smoking at 1-month and 10% at 6-months.

Despite similar follow-up outcomes for the groups in terms of smoking abstinence, the contingency management group had longer time to relapse. Specifically, given one individual who was abstinent from smoking in the contingency management group, and one in the smoking cessation-as-usual group on any given day during the 6-month study period, the contingency management participant was 1.6 times more likely to remain abstinent the following day.

Contrary to the authors’ prediction, there were no differences on alcohol abstinence or combined alcohol and other drug abstinence at the end of the smoking intervention, or at 1-month and 6-month follow-ups.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT?

This study showed that it is possible to improve smoking cessation outcomes in addiction treatment patients despite the many challenges present.

While rewards for abstinence are in place, smoking cessation outcomes may be three times higher than with usual evidence-based smoking cessation including a nicotine patch and cognitive-behavioral therapy. This is similar to the effect of contingency management on alcohol and other drug use. These strategies that offer monetary reward for abstinence (i.e., a contingency) are among the most effective in the substance use disorder treatment field, and are powerful while these rewards are in place. Outcomes typically revert back to baseline levels after the contingencies are removed, however, without other treatments to supplement the contingency management. As shown in this trial of evidence-based smoking cessation for individuals in substance use disorder treatment, only 10% were abstinent (i.e., for 7 or more consecutive days) at 6-months.

By comparison, a meta-analysis (a study combining results several studies at once) of nicotine replacement therapy more generally showed that 22% of those receiving treatment were smoking abstinent at 6-month follow-up.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The sample size was quite small, and consisted of male Veterans. Thus it is not clear whether these findings apply to others in addiction treatment.

NEXT STEPS

There are still many unanswered questions about the best ways to help individuals with alcohol and other drug use disorder quit smoking. Should smoking cessation be incorporated into substance use disorder treatment or should it be the focus at a later point?

In one randomized controlled trial, for example, those who got a smoking cessation intervention 6 months after entering substance use disorder treatment had better alcohol abstinence rates and similar smoking abstinence rates compared to those who got it during (i.e., concurrent with) this substance disorder treatment episode.

Furthermore, if it is, in fact, incorporated into substance use disorder treatment, should be integrated into treatment so that everyone gets it while they get other treatment? Should it be optional alongside other treatment so that only those interested get it? These important questions will all require further research to answer.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Counseling to help you quit smoking cigarettes while you are also in early recovery from alcohol and/or other drug use disorder could be improved by offering monetary rewards for abstinence. However, this benefit will only last as long as the rewards are provided. During this time, you are encouraged to explore what motivates you to quit smoking cigarettes and why you would choose to remain quit once the rewards are no longer in place.

- For Scientists: As with alcohol and other drugs, this and many other studies show contingency management is likely to boost smoking abstinence rates over and above evidence-based smoking cessation treatment including nicotine replacement therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. Several studies have shown that individuals in addiction treatment can benefit from smoking cessation, but that this benefit declines sharply over time. Addiction treatment participants have poorer smoking cessation rates compared to others that receive smoking cessation interventions. Optimal ways to facilitate smoking cessation among individuals in substance use disorder treatment require further investigation.

- For Policy makers: Contingency management is likely to increase smoking abstinence among substance use disorder treatment patients when added to evidence-based smoking cessation as usual, including nicotine replacement therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. Current data suggest that at least offering smoking cessation treatment to individuals who want it in substance use disorder treatment will not harm them. That said, one study showed that offering smoking cessation after substance use disorder treatment – rather than during — actually produces better substance use outcomes with similar rates of smoking abstinence. Definitive conclusions about the interplay between smoking cessation and substance use disorder treatment cannot be made at this point. Consider increased funding toward research on this important issue.

- For Treatment professionals and treatment systems: The current research suggests adding contingency management to evidence based treatment as usual for smoking cessation is likely to help while the rewards are in place. Also, overall, among individuals interesting in quitting cigarettes, those who receive smoking cessation interventions typically have better smoking abstinence rates and similar substance use outcomes over the short-term (i.e., 6 months or less). That said, one study showed that individuals who received smoking cessation 6 months after substance use disorder treatment had better alcohol abstinence rates over an 18-month period than those who received smoking cessation during treatment, despite similar rates of smoking abstinence. Clearly, more research is needed to flesh out the best way to help addiction treatment patients quit smoking.

CITATIONS

Cooney, J. L., Cooper, S., Grant, C., Sevarino, K., Krishnan-Sarin, S., Gutierrez, I. A., & Cooney, N. L. (2016). A Randomized Trial of Contingency Management for Smoking Cessation During Intensive Outpatient Alcohol Treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment.