Race & Treatment Outcomes for Cocaine Misuse

Race and ethnicity are very often considered in studies of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment and recovery. However, they are typically controlled for in statistical analyses to isolate another effect of interest (e.g., the effect of treatment on substance use, irrespective of whether the patient is White, African American, Latino, etc.).

While necessary, this does not allow authors to speak to the possibility of differential treatment effects by race.

This may be particularly important in studying cocaine misuse among African Americans, given the compounding influence of both race-related cardiac vulnerabilities and the physical effects of cocaine on cardiac functioning and disease.

In this secondary data analysis of six randomized controlled trials of contingency management for individuals with cocaine use disorders, Montgomery, Carroll, and Petry tested whether African Americans (n = 444) and Whites (n = 403) had differential treatment outcomes during the index treatment episode and at 9-month follow-up.

They also tested whether any differential outcomes held for individuals with better (negative cocaine toxicology screen upon study entry) or worse (positive cocaine toxicology screen upon study entry) initial treatment prognosis.

Based on prior studies, authors hypothesized that African Americans would have poorer treatment retention and worse drug use outcomes.

In brief, contingency management, which has among the largest body of evidence in the treatment/recovery literature, is a time-limited treatment (12 weeks in the current study) often tested in combination with standard treatment (i.e., compared to standard treatment alone), providing rewards for negative toxicology screens and/or treatment attendance. In the current study, standard treatment consisted of group therapy 3 to 5 days per week for 2 to 4 weeks, and one continuing care group per week thereafter (for up to 12 months) covering coping skills, HIV/AIDS education, relapse prevention, and 12-step-related interventions (that were not described in detail).

On average, African American participants were significantly older than Whites (38 vs. 36 years old), had similar number of years of education (both approximately 12), but significantly lower annual incomes (about $7,000 vs. $10,000). African Americans were significantly less likely to have a negative cocaine screen upon study entry (76% vs. 82%), had more severe drug use composites on the Addiction Severity Index (but not significantly so, p = .08), but had similar days of cocaine, alcohol, and heroin use in the 30 days prior to study entry. Primary outcomes of interest were proportion of negative toxicology screens (for cocaine, alcohol, and opioids), longest duration of consecutive weeks abstinent, and weeks retained in treatment.

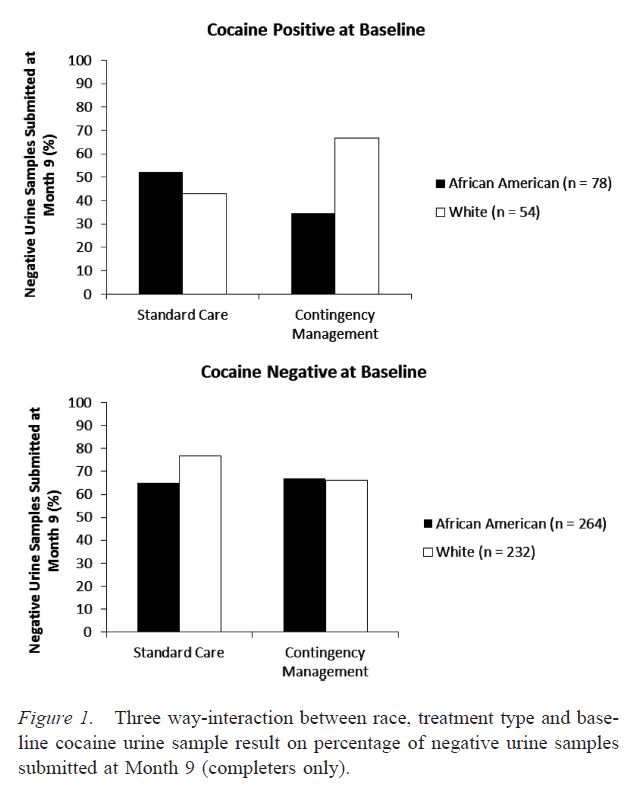

Authors’ hypotheses were partially supported. African Americans had a lower proportion of negative toxicology screens than Whites – but only among those with poorer prognosis (an initial positive screen). This also depended on whether participants received contingency management plus standard care or standard care alone. Among those with this poorer prognosis, Whites responded well to contingency management – they had 30% more negative toxicology screens (65 vs. 33%) and remained in treatment longer (7.3 vs. 5.6 weeks) than those receiving only standard care. African Americans with this poor prognosis did not respond as well – they had 14% more negative toxicology screens (42 vs. 28%) and actually remained in treatment fewer weeks (5.7 vs. 6.2) than those receiving only standard care. There were no differences in longest duration of abstinence.

Similarly at 9-month follow up, among those with poor prognosis, Whites again had better outcomes if receiving contingency management (65% vs. 35%), though there was no difference for those receiving only standard care with both African Americans and Whites providing negative screens 45% of the time. See Figure 1 below for an illustration of this differential treatment outcome by race effect. Among those with good prognosis, though, roughly 60% had a negative toxicology screen (for both Whites and African Americans and for both treatment conditions).

IN CONTEXT

In context of the impact of race on treatment outcomes for cocaine use disorders, whether an individual has a positive or negative toxicology screen at intake is an extremely important variable to consider.

Positive toxicology screens should be thought of as a poorer initial prognosis – a vulnerability accentuated if one is African American. These individuals do not respond as well as their White counterparts during or following treatment.

Although it is beyond the scope of this study, recovery capital appears to be relevant. It is possible that African Americans with cocaine use disorders with poorer prognosis do not benefit as much from an evidence-based contingency management approach because they have fewer resources at intake to bear on recovery efforts (e.g., lower financial resources) or their socio-environmental living situation places them at higher risk for continued use (see Kelly and Hoeppner 2015).

As such, it is key for treatment staff to identity not only those with poorer prognosis, but also to determine how life circumstances might make recovery efforts more or less likely, and ways in which staff can bolster patients with more difficult life circumstances.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Talk to providers about perceived difficulties initiating abstinence and perceived recovery barriers early on in treatment.

- For scientists: Initial prognosis and race are important variables to measure and include in explanatory and predictive models in order to understand treatment outcomes. Next steps to this risk-focused study include examining protective factors or possible interventions that might mitigate this risk.

- For policy makers: If not already doing so, consider developing and funding culturally-sensitive programs to aid treatment seekers with fewer resources.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: The interplay between race/culture, clinical factors, and SUD profiles is complex. If not already doing so, consider identifying life context as well as intra-individual risk factors in crafting an initial treatment plan.

CITATIONS

Montgomery, L., Carroll, K., & Petry, N. (2015). Initial abstinence status and Contingency Management treatment outcomes: Does race matter?. J Consult Clin Psychol. doi: 10.1037/a0039021