Timing is everything: Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in pediatric primary care improves both patient and health care use outcomes

Research shows that screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT; a public health approach to substance use prevention and early intervention) in pediatric primary care improves patients’ substance use outcomes, but few studies have examined its effects on health care use or the development of medical or mental health comorbidities over time. In this study, patients whose pediatricians were randomized to deliver SBIRT had better substance use, mental health, and medical outcomes over a 3-year period. The results provide a window into how providing SBIRT in primary care may reduce health care use and improve adolescent health.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is a public health approach to substance use prevention and early intervention and may reduce mental health symptoms as well. Although research shows brief interventions are effective at reducing substance use and related consequences among adolescents, few have examined its effects on health care use. There is evidence that SBIRT may be more cost-effective than standard care, but those studies have largely focused on adults. In this study, the authors sought to address this gap by examining the long-term impact of SBIRT, compared to standard treatment, on service use and the prevalence of substance use, mental health, chronic medical conditions over the 3-year period after their initial screening.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study used data collected as part of a randomized clinical trial of SBIRT implementation for adolescents ages 12 to 18 years at Kaiser Permanente’s integrated health care system in Oakland, CA. In the original study, there were a total of 1,871 adolescents across 3 intervention groups: (1) a pediatrician-only condition consisting of pediatricians who were trained to screen and (if needed) deliver brief interventions and refer to specialty substance use or mental health treatment; (2) an embedded behavioral clinician condition in which pediatricians administer the initial assessment and (if needed) refer patients to an embedded behavioral clinician for further assessment, brief intervention, and referral to treatment; and (3) a usual-care condition in which pediatricians had access to the electronic health record screening tools but no formal SBIRT training. In that initial study, the authors found that pediatrician and behavioral clinician conditions had better screening, assessment, and brief intervention rates than the usual-care conditions. Also, patients in the pediatrician-only and usual-care conditions had higher odds of being referred to specialty treatment than those in the behavioral clinician condition.

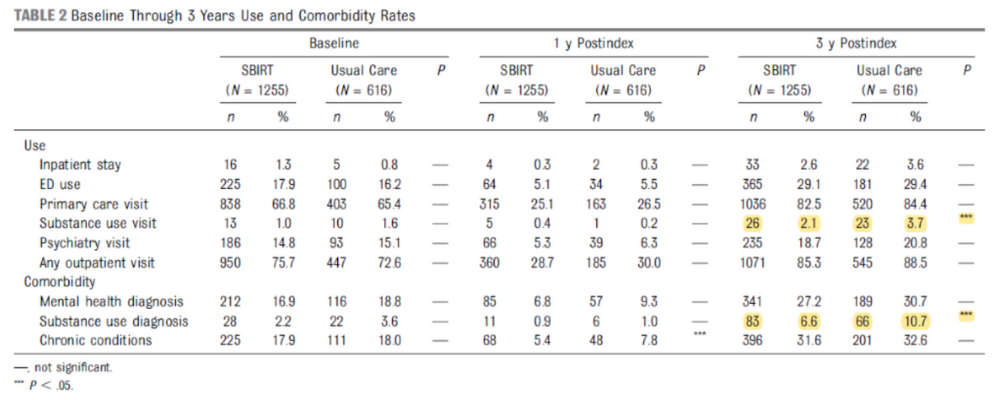

In this study, the two SBIRT conditions were combined to make one SBIRT group which was compared to the usual–care condition on substance use, mental health, and medical outcomes both at 1 year and 3 years after the initial screening. They used this approach to try and examine, as best they could, whether participation in SBIRT decreased health care use and prevalence of substance use, mental health, medical diagnoses in a sample of 1,871 teens who endorsed either the substance use or mental health symptoms on the screening tools. Measures of substance use, health care use, as well as mental health and medical diagnoses were culled from patients’ electronic health records. Healthcare use was defined as total visits for the service in question from the screening until the specified follow-up. Presence of a mental health or medical diagnosis was defined as presence of any condition at any point during each time period.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Figure 1. Source: Sterling et al., 2019

Adolescents that received SBIRT had more substance use treatment visits and lower likelihood of having an SUD diagnosis 3 years after the initial screening.

Among the 1,871 eligible adolescents, there was no difference in substance use rates between conditions at baseline through 1 year. However, those who received SBIRT rather than usual–care were more likely to have had substance use treatment visits and were less likely to have a substance use diagnosis over the 3-year period.

Figure 2.

Compared to usual-care, those who received SBIRT had fewer psychiatry visits 1 and 3 years later.

Adolescents who received SBIRT rather than usual–care had fewer psychiatry visits 1 and 3 years later. Similarly, compared with those in usual–care, those in the SBIRT group had fewer psychiatry and total outpatient visits over the 3 years. There were no differences in emergency room or primary care visits. Also, those who received SBIRT were less likely to have a mental health or medical diagnosis after 1 year compared to those in usual–care.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study is among the first to examine associations between access to SBIRT and health care service use in adolescents. Among those in the SBIRT group, the adolescents that received SBIRT had more substance use treatment visits and lower likelihood of having as SUD diagnosis 3 years after the initial screening. They also found the SBIRT group had lower use of psychiatry services at both 1 and 3 years and lower overall outpatient use at 3 years. These lower use rates are particularly notable because they serve as important proxy indicators of health and well-being. Importantly, they also found that the adolescents in the SBIRT group were less likely to have a mental health or a medical diagnosis at 1 year, suggesting that offering SBIRT in pediatric primary care may have an enduring impact on both health and health care use during this critical developmental period.

Taken together, these findings underscore the importance of screening for substance use problems and brief intervention or referral to more intensive treatment when necessary, occurring at every visit as for other health conditions, particularly given that adolescence is such a critical developmental period for substance use and mental health conditions. Moreover, this is in line with research that shows the earlier someone begins some kind of treatment after beginning to use alcohol or other drugs, the shorter the time to sustained remission (i.e., to achieve 1+ year without problematic substance use).

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study was conducted in an integrated health care system with an insured population and may not be generalizable to uninsured populations.

- The trial did not recruit patients to obtain study related information, but instead relied on electronic health record-based clinical information collected during regular care.

- The analysis did not account for nesting of patients within providers as difference in individual providers may account for some group differences or lack thereof.

- This was an intent-to-treat analysis in which outcomes were examined among all eligible patients in both groups, regardless of whether they received a brief intervention. This means this study has limited ability on detecting differences between groups, because each intervention group included patients that did not receive the intervention, and by extension did derive benefit from it in the final outcome. Despite that, it is a rigorous approach that allows for the greatest generalizability.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study showed that adolescents who received SBIRT had more substance use treatment visits and lower likelihood of having an SUD diagnosis 3 years after the initial screening. Teens with access to SBIRT also had fewer co-occurring mental health diagnoses and psychiatry visits at 1 year as well as fewer outpatient use over 3 years. These findings, coupled with previous SBIRT research, highlight the lasting effects of brief intervention with adolescents on substance use, medical, and mental health outcomes. This is particularly important given that adolescence is such critical developmental period for the onset of substance use and mental health conditions, and research shows the earlier someone gets in treatment after beginning to use, the quicker they achieve remission.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study showed that adolescents who received SBIRT had more substance use treatment visits and lower likelihood of having an SUD diagnosis 3 years after the initial screening. Teens with access to SBIRT also had fewer co-occurring mental health diagnoses and psychiatry visits at 1 year, as well as fewer outpatient use over 3 years. These findings underscore the importance of screening for substance use problems and brief intervention or referral to treatment as necessary, occurring at every visit as for other pediatric health conditions, particularly given that adolescence is such a critical developmental period for substance use and mental health conditions.

- For scientists: This study showed that adolescents who received SBIRT had more substance use treatment visits and lower likelihood of having an SUD diagnosis 3 years after the initial screening. Teens with access to SBIRT also had fewer co-occurring mental health diagnoses and psychiatry visits at 1 year as well as fewer outpatient use over 3 years. These promising results, coupled with previous work, highlight the need to determine the best way to integrate SBIRT into existing healthcare systems and disseminate the SBIRT approach to other frontline healthcare providers (e.g., dentists, urgent care). Further research examining the cost-benefits of providing universal SBIRT among adolescents in primary care settings and understanding the mechanisms through which SBIRT helps young people and their families could promote greater dissemination and use.

- For policy makers: This study showed that adolescents who received SBIRT had more substance use treatment visits and lower likelihood of having an SUD diagnosis 3 years after the initial screening. Teens with access to SBIRT also had fewer co-occurring mental health diagnoses and psychiatry visits at 1 year, as well as fewer outpatient use over 3 years. These findings underscore the importance of screening for substance use problems and providing brief intervention or referral to more intensive treatment as necessary, occurring at every visit as is done for other common pediatric health conditions. Given that alcohol and other drug use disorders most often begin during adolescence and confer such a large burden of disease, disability, and premature mortality, thus resulting in immense economic costs, dissemination and universal implementation of SBIRT in pediatric primary care may be a prudent public health policy.

CITATIONS

Sterling, S., Kline-Simon, A. H., Jones, A., Hartman, L., Saba, K., Weisner, C., & Parthasarathy, S. (2019). Health care use over 3 years after adolescent SBIRT. Pediatrics, 143(5). doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2803