Is there a “social cure”? Family and friends matter for recovery capital

There is a long history of research and clinical experience showing how family and friends impact substance use and outcomes during addiction treatment and early recovery. Research on the risk and protective effects of these relationships at various stages of recovery can provide basic knowledge about the recovery process. This study assessed if relationship status, living with children, and social network characteristics are associated with recovery capital.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The nature of an individual’s social network – the individuals with whom they are socially connected and interact with most often – relates to both substance use and how they fare during treatment and early recovery. More knowledge about how an individual’s family and friends, and the nature of those relationships, relate to recovery over the long-term and to outcomes beyond substance use, can help providers, policy makers, and individuals in recovery themselves to gain a more comprehensive understanding of whether, to what extent, and how social processes can make a difference for individuals in recovery. For example, do social networks with more individuals in recovery relate to positive outcomes for those with more time in recovery as well as those who are earlier in the recovery process? Also, how do key family relationships that for some can be both sources of joy and stress (e.g., parenting) relate to recovery outcomes? To help answer these questions, researchers explored if relationship status, living with children, or social network characteristics were associated with recovery capital among individuals at varying stages of addiction recovery.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

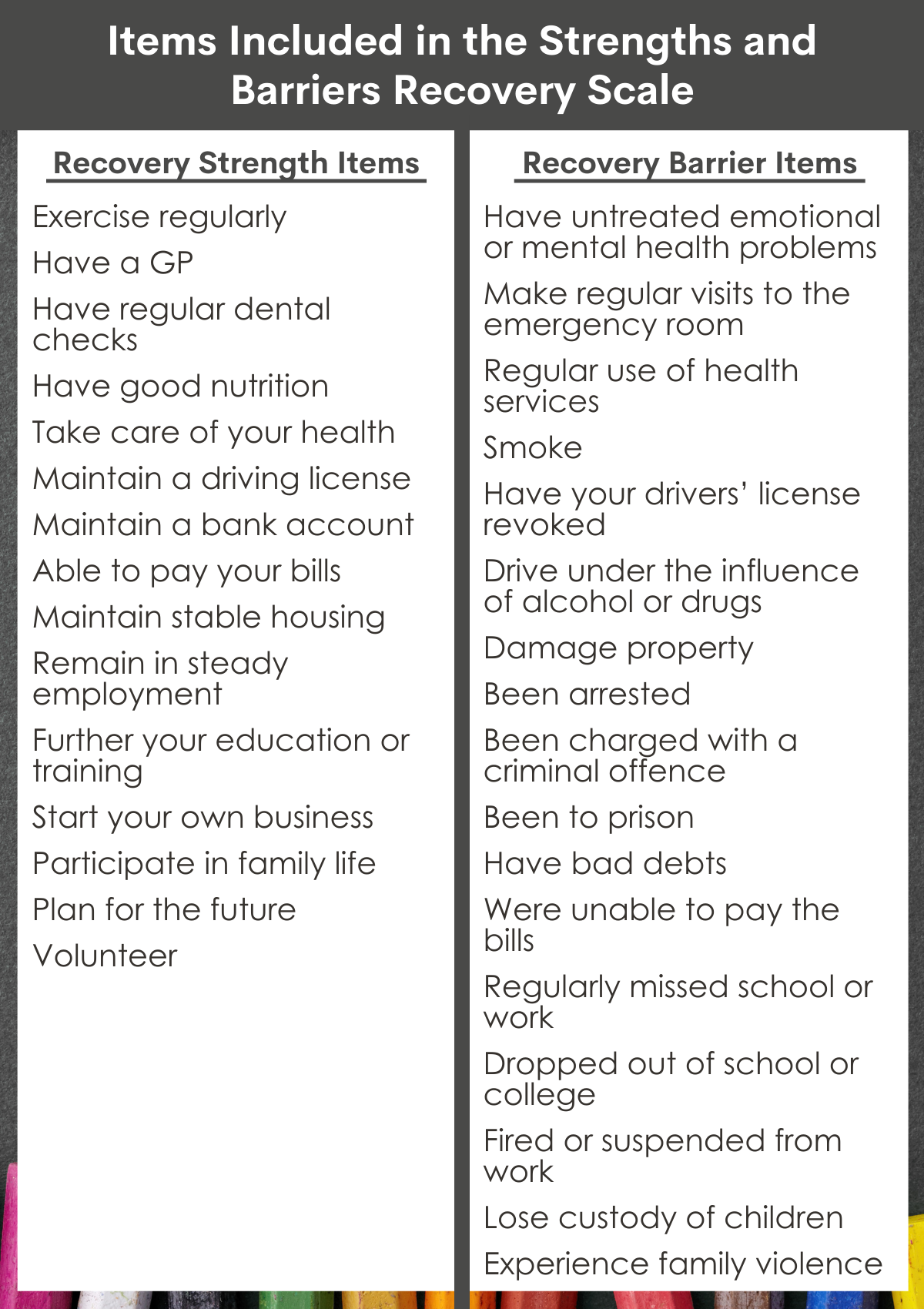

In this study, researchers combined data from the European study of recovery pathways (REC-PATH; n = 776) and supplemental data collected through a partnership with the international Recovered Users Network (RUN; n = 537) for a final sample of 1,313 European adults in recovery from illicit substance use (not including alcohol; hereafter referred to as “recovery”). All participants completed the Life in Recovery survey (LiR). The survey was further broken down into a novel way to measure recovery capital: the Strengths and Barriers Recovery Scale (SABRS). The original survey had 44 items. Two items were dropped because they did not apply to the population (‘did not have health insurance’ and ‘lost the right to vote’). Ten additional items were dropped because they were dependent on other events. For example, ‘having your driver license restored’ depends on having had a driver’s license in the first place and that it was revoked. The final version of this recovery capital measure is a 32-item scale counting the number of recovery strengths and barriers (up to 15 and 17 respectively) both retrospectively during active addiction and since coming in to recovery.

Items included in the strengths and barriers recovery scale.

The original Life in Recovery survey and the subsequent recovery capital scale take a retrospective approach that asks participants about their recovery capital since entering recovery as well as their recovery capital while they were in active addiction. Each participant was asked to indicate (yes/no) for each strength and barrier they experienced “since you came into recovery” and “while in active addiction”. This results in four scores: recovery strengths in active addiction, recovery barriers in active addiction; recovery strengths in recovery; and recovery barriers in recovery. Each score represents the sum of endorsed strengths or barriers, which means the total number of “yes” responses for each subscale is the final score for that subscale. This retrospective approach allows researchers to estimate change from active addiction (i.e., in the past) to their recovery (i.e., currently). In other words, participants reported their strengths and barriers while in recovery based on their functioning and life status since entering recovery, and they reported on their strengths and barriers in active addiction by reflecting on these same experiences during active addiction. To calculate change, the research team subtracted the number of strengths/barriers in active addiction from the number in recovery.

All participants completed the survey only once, and the majority used an online platform to do so. The researchers then explored the results by breaking them down across recovery stage, relationship status, living with children, number of close friends, proportion of using friends, and proportion of friends in recovery. Recovery stages were based on the Betty Ford Institutes Consensus Group’s categorization of ‘early recovery’ (<1 year), ‘sustained recovery’ (1-5 years) and ‘stable recovery’ (>5 years). Relationship status and living with children were transformed into binary measures – married / cohabitating or not and living with dependent children or not. Close friends were determined by asking participants to report the number of people they felt they could talk to about important things. They also assessed if these social relationship characteristics and other key social factors (e.g., gender, education, etc.) were independently linked with changes in strengths from active addiction to recovery, controlling at the same time for each of the other variables, to try and isolate the effect of each variable with improvements in strengths from addiction to recovery.

The sample was on average 40.3 years old and 65% male. In terms of family, 39.8% were married or co-habiting, and 35.6% had dependent children living with them. Along friendship connections, 69.5% had four or more people they could discuss important things with, 59.3% had no people in their network using illicit substances, and 33.4% reported that more than half but less than all of their social network was in recovery.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Sustained recovery was associated with more recovery capital.

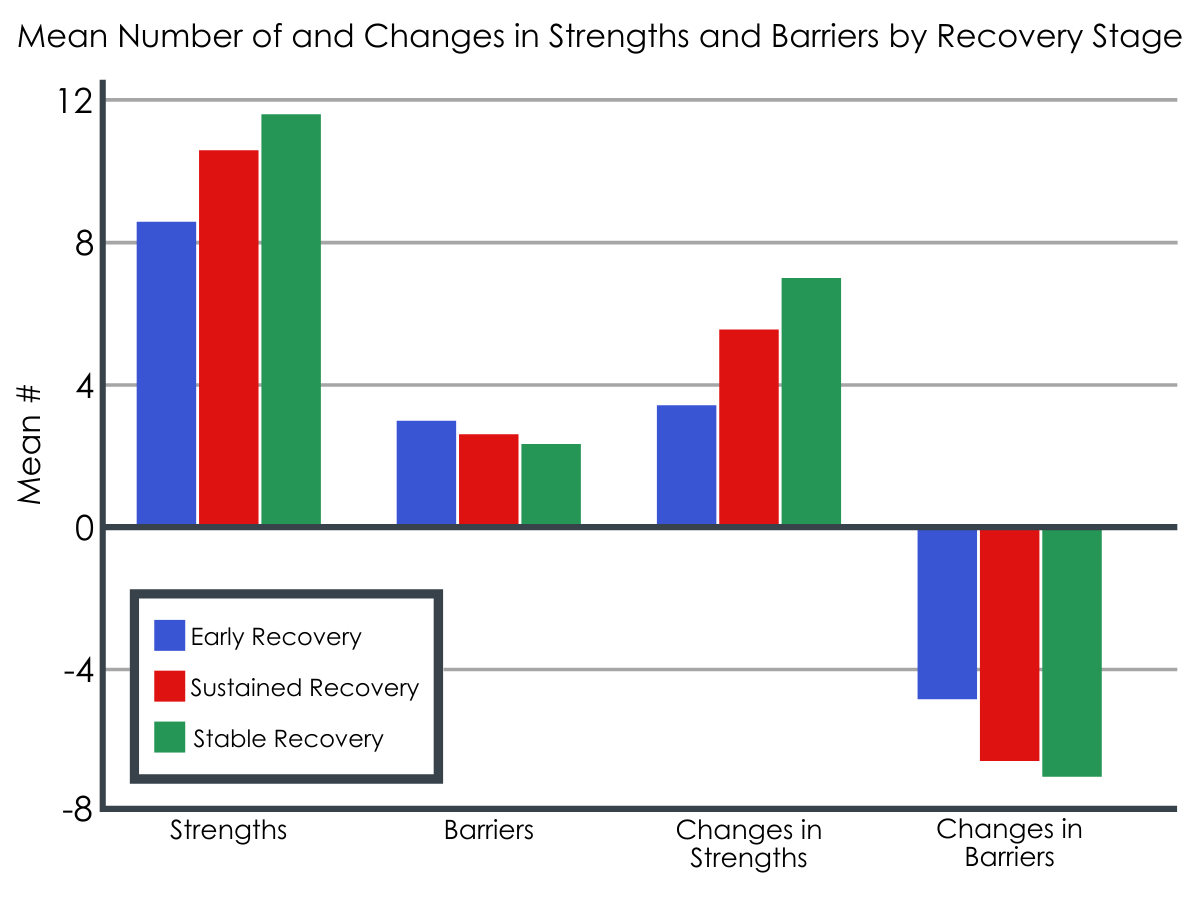

Overall, participants reported an average increase of 6 strengths and an average reduction of 6 barriers. Increase in strengths from addiction to recovery was strongly related to decreases in recovery barriers. Each subsequent recovery stage (i.e,. early vs. sustained vs. stable) was associated with more recovery strengths. However, there were only significant differences in barriers for those in early recovery – that is, sustained and stable recovery were associated with a similar number of barriers. The same pattern appeared for perceived changes in strengths and barriers when moving from active addiction to recovery.

Mean number of strengths and barriers and the changes in both by recovery stage. There was a theoretical maximum of 15 strengths and 17 barriers that could be present or change.

Being in a stable relationship (married or cohabitating) was linked with more recovery capital.

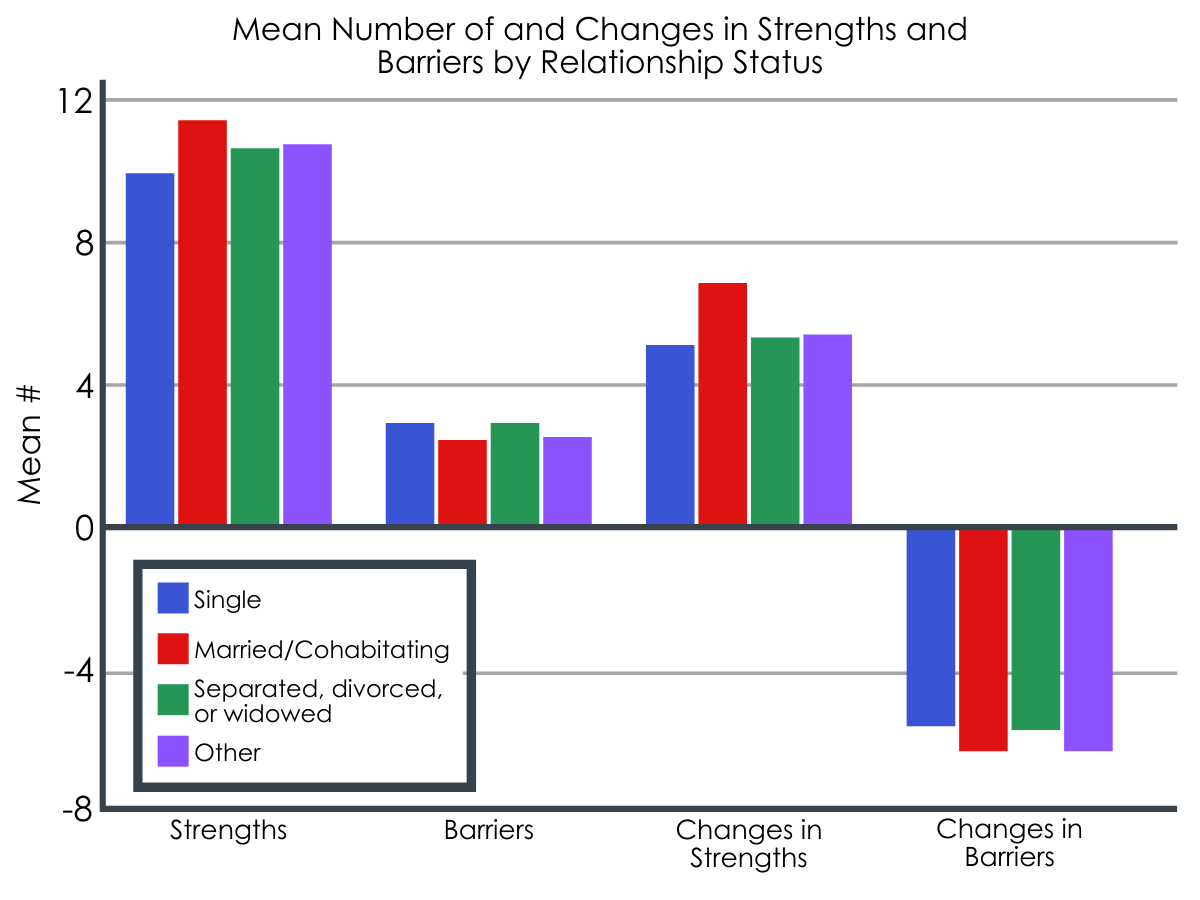

Participants that identified as being married or cohabitating reported more strengths and fewer barriers compared to those that identified as single, separated, divorced, or widowed, and those with an “other” relationship status. Living with a partner was also related to greater improvements in both strengths and barriers when looking back to their active addiction.

Mean number of strengths and barriers and the changes in both by relationship status.

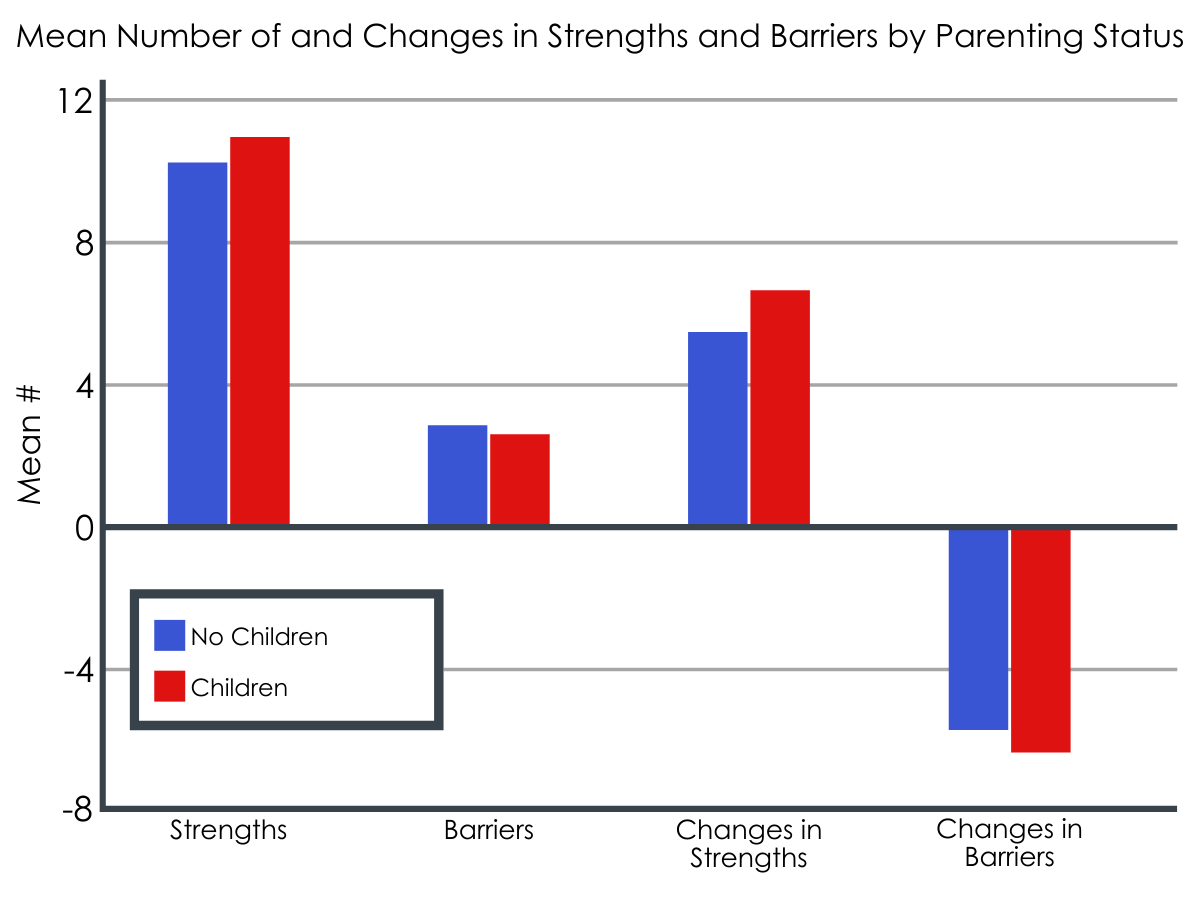

Living with children was associated with more recovery strengths.

Similarly, participants that reported living with children also reported more strengths in recovery compared to those not living with children. There were no differences between the two groups in the number of barriers in recovery. Having children was associated with both greater improvements in strengths and barriers from active addiction to recovery. However, when all sociodemographic and relationship characteristics were considered simultaneously, living with children was not uniquely linked with changes in strengths from active addiction to recovery.

Mean number of strengths and barriers and the changes in each by parenting status.

Women were more likely to be living with dependent children. For both men and women, living with dependent children was associated with more strengths in recovery.

Having more friends to talk to, fewer friends using illicit substances, and more friends in recovery are all linked with greater recovery capital.

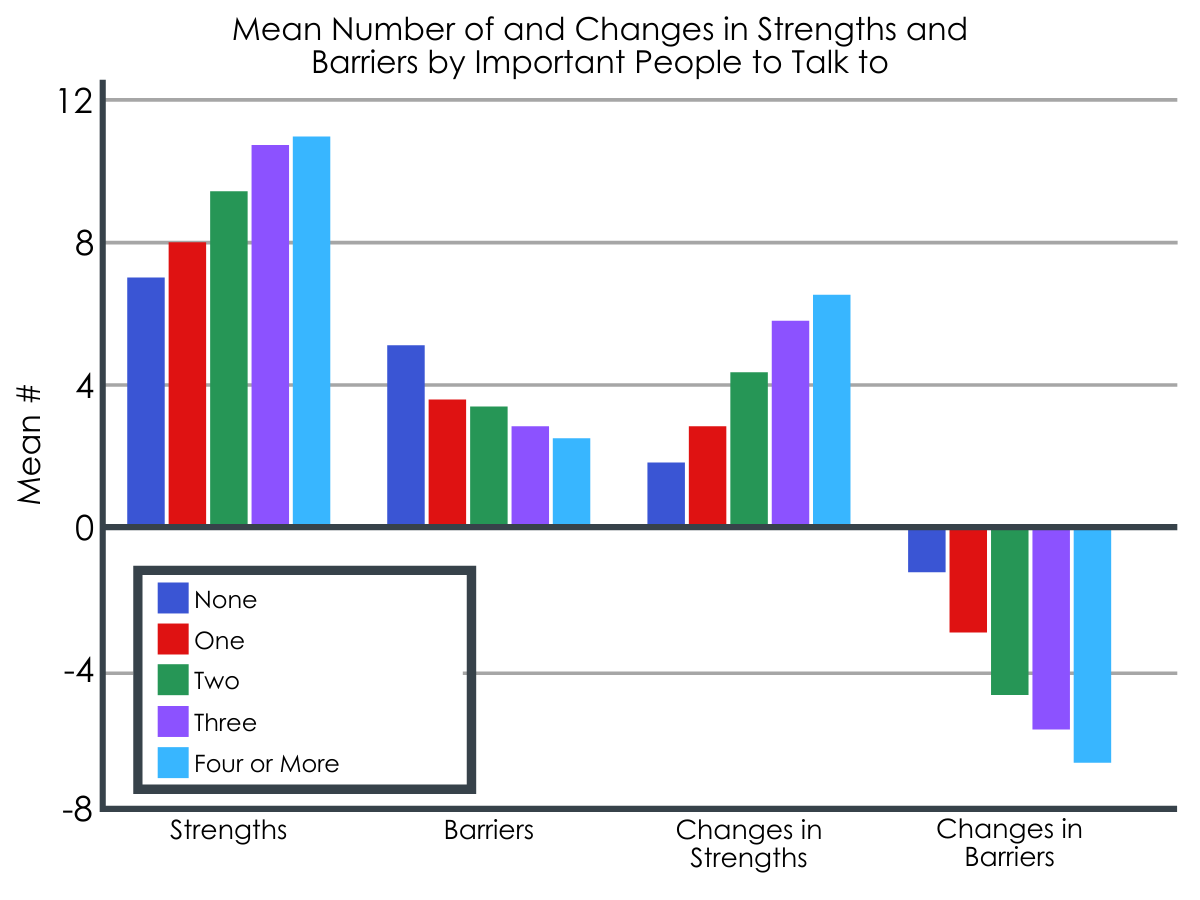

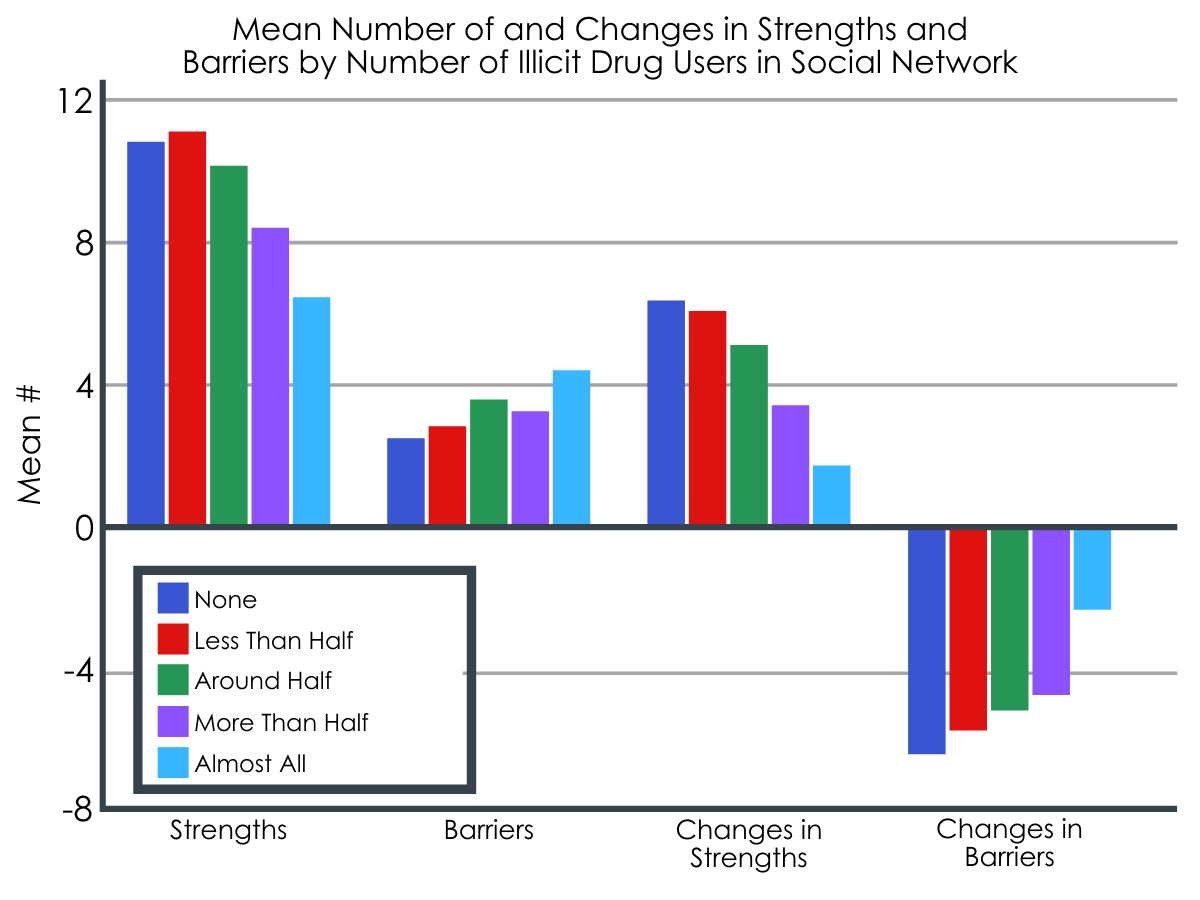

The researchers found that those with more close friends reported greater strengths and fewer barriers in recovery. The number of close friends was grouped in to five categories: none, one, two, three, and four or more. Respondents in each successive category had more strengths and fewer barriers at the time of the survey. They also reported greater increases in strengths and greater reductions in barriers from active addiction to recovery. A similar pattern was also found for the proportion of a person’s network that were in recovery. One difference is that participants who reported their whole network in recovery had fewer strengths and more barriers compared to those that had more than half but less than all their network in recovery. The reverse pattern of results was found for the proportion of people in a person’s social network using illicit substances. Those with a smaller proportion of their network using illicit substances reported more strengths and fewer barriers.

Mean number of strengths and barrier and the changes in each by number of important people to talk to in one’s life.

The researchers found that those with more close friends reported greater strengths and fewer barriers in recovery. The number of close friends was grouped in to five categories: none, one, two, three, and four or more. Respondents in each successive category had more strengths and fewer barriers at the time of the survey. They also reported greater increases in strengths and greater reductions in barriers from active addiction to recovery. A similar pattern was also found for the proportion of a person’s network that were in recovery. One difference is that participants who reported their whole network in recovery had fewer strengths and more barriers compared to those that had more than half but less than all their network in recovery. The reverse pattern of results was found for the proportion of people in a person’s social network using illicit substances. Those with a smaller proportion of their network using illicit substances reported more strengths and fewer barriers.

Mean number of strengths and barriers and the changes in each by amount of illicit drug users within one’s social network.

Life experiences outside the family also matter for recovery capital.

The research team also sought to explore what life experiences were uniquely associated with improved strengths from active addiction to recovery. They examined several variables one at a time, including demographic characteristics as well as measures of addiction severity (e.g., duration of substance use), current functioning, and history of addiction service involvement.

With respect to demographic characteristics, being female versus male, having “greater levels of education” (the research team did not specify how they defined the education variable for analysis), and being married (versus single) were each independently associated with greater increases in strengths from addiction to recovery. With respect to addiction severity, shorter substance use careers was associated with greater increases in strengths. With respect to current functioning (last 30 days), no criminal justice involvement, employment, no acute housing need, and educational involvement were associated with greater increases in strengths. While no individual treatment or recovery support service was associated with improved strengths, participation in the combination of inpatient and outpatient treatment as well as 12-step mutual-help attendance (versus not receiving the combination) was associated with improved strengths. The magnitude of these relationships were generally modest. For example, the largest effects were related to housing and employment, such that those with an acute housing need had strength change scores 1.2 points lower than those without such a need, and current full-time employment associated with strength change scores 1 point higher than those without current employment.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Best and colleagues used a community sample of individuals at various recovery stages to explore the relationship between social factors, other clinical and recovery-related factors, and recovery capital. While they found marriage and having dependent children were associated with better recovery capital – defined here as more strengths (e.g., exercising regularly) and fewer barriers (e.g., regularly missed school or work) – only marriage was associated with an increase in strengths over time, when controlling for the effects of other variables on strength changes. Importantly, the change scores were based on the difference between how individuals reported strengths currently in recovery relative to how they remember these strengths during addiction. So, while it’s possible that factors like being married might have some causal impact on improved recovery strengths over time, it is equally possible that individuals with improved recovery strengths are doing well in their lives, putting them in position to initiate and develop meaningful relationships like marriage.

How to maintain and increase recovery capital through social relationships may look different depending on length of time in recovery. Although each additional stage of recovery was linked with more strengths, the same was not true for barriers. There are steady reductions in barriers during early recovery (<1 year), but there appears to be a leveling off between sustained (1-5 years) and stable (>5 years) recovery. This may be attributable to a plateauing or ceiling effect found in other work. It may be important to consider not only how to reduce barriers, especially in early recovery, but how to simultaneously cope with long-lasting barriers throughout recovery stages.

Future work may also help to clarify if the timing of relationship development (e.g., marriage, parenthood) changes recovery capital. For example, living with children was associated with having more strengths overall but not changes in strengths from active addiction to recovery. Parenthood may provide a source of joy and motivate recovery. It may also be significant source of stress. The stage of recovery that someone is in when becoming a parent may necessitate different levels/types of support. Future work aimed at maintaining and increasing recovery capital could focus on the underlying mechanisms of these social relationships for those in recovery as well as how the timing of relationships influences recovery capital.

Results of this study also showed that those with a greater number of close friends had more strengths and fewer barriers. In terms of composition, having a smaller part of someone’s network currently using substances and a larger proportion in recovery was also linked with more recovery capital. However, including a range of identities (e.g., those in and not in recovery) in a person’s social network may be warranted as those with all their network in recovery had fewer strengths and barriers than those with more than half but less than all. This may mean that incorporating a diversity of identities brings a variety of supports. Alternatively, these findings may indicate that individuals who are struggling due to fewer recovery strengths are actively engaging others in recovery for support. Due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, we cannot determine which, if either, of these possibilities is true. These findings, in tandem with existing scholarship highlighting the benefits of social support, demonstrate that learning to build and maintain numerous close, healthy friendships may help those in recovery bolster their recovery capital. Future work may explore how to assist individuals in all recovery stages learn relationship skills.

Also, of particular importance, housing and employment were both related to enhanced recovery strengths over time, though the direction of the effect – whether people doing well are in position to obtain housing and sustain employment or whether these factors support enhanced recovery outcomes (or some dynamic mutual influence) – cannot be determined from these cross-sectional data. In a nationally representative recovery sample, too, employment was also associated with better functioning and subjective quality of life. On the other hand, for individuals with severe mental illness, interventions to facilitate stable housing like Housing First, may not improve their substance use or mental health difficulties, though importantly, they do experience improved quality of life. Whether and how employment and housing relate to other aspects of recovery (substance use, mental health, physical health, etc.) over time are critical areas for future study.

Finally, the researchers in this study used a novel measure of recovery capital, based on individuals’ perceived recovery strengths – such as exercising regularly – and barriers – such as regularly missed school or work. There are many validated measures currently used to capture recovery capital, including the Addiction Recovery Capital scale (and its brief version) and the Substance Use Recovery Evaluator, or SURE. In the future, research can help determine whether this is a useful measure of recovery that is sensitive to change or helps predict how people in addiction recovery will fare over time.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The sample only included those in recovery from problematic illicit drug use and may not generalize to those with primary alcohol problems who comprise the majority of people with drug problems.

- As mentioned above, the study was cross-sectional and, therefore, any causal inferences should not be inferred without future longitudinal investigations.

- The survey methodology relied on participants’ retrospective recall of life in active addiction, which could be prone to bias, either over or underestimating recovery capital during active addiction.

- The stem question used to screen for people in recovery let participants define for themselves what recovery meant. While this might have caused some confusion as to what recovery means, it is common to use self-identification to screen for participation in community recovery samples. Future estimates and findings may vary depending the definition used and on the recovery pathway taken.

- Participants were also recruited through convenience and snowball methodologies, which increases the potential for selection bias. Those that participate may not be representative of the population of individuals who identify as in recovery.

BOTTOM LINE

The team of researchers in this study found that among European adults in recovery from illicit substances, those who are married or cohabitating as well as those living with dependent children report more recovery capital compared to those that are not. Similarly, those with larger social networks, fewer people who use illicit substances and more people that are in recovery also report more recovery capital. Finally, even when controlling for a host of other demographic, clinical, and recovery-related factors, being employed and without any acute housing needs were associated with improvements in recovery strengths. All findings in this study, however, were based on a cross-sectional survey, so that it cannot be determined if these characteristics caused greater recovery capital, or individuals doing well in their recoveries also show greater social involvement, or both. These findings should be treated as important hypotheses to be tested in future longitudinal studies where individuals are followed over time.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Family and friends have been found to impact substance use and misuse. The researchers found that being married and living with children may also be an important resource for those in recovery. Having more friends, especially when they are mostly in recovery, may also be an important resource for those in recovery. Seeking out and leveraging pro-recovery relationships, both family and peers, may help achieve stable recovery.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Other researchers have previously found that including family in the treatment process improves outcomes compared to individual-based therapies. However, we are still learning about the strengths demonstrated and barriers experienced by people already identifying as being in recovery. Family and peer relationships may be one resource to incorporate into treatment planning and continuing care. Doing so may help reduce the time to problem resolution and increase quality of life. Moreover, considering the number and type of other, non-familial relationships may help gauge relative strengths and barriers for individuals. Improving the strength and health of both family and friendship relationships may further help individuals achieve stable recovery.

- For scientists: There is substantial room for future research to build off the current study. First, the cross-sectional design limits any casual claims about the link the between social relationships and recovery capital. A more rigorous prospective study design may be able to tease apart if and how relationships are linked to changes in recovery capital. Second, factors that may change these findings such as primary substance or pathway of recovery were not included. Third, the causal order of relationship formation or dissolution and changes in recovery capital could not be established in this study. Future investigators should explore how relationship changes impact recovery capital and vice versa. Fourth, future researchers should explore which sociodemographic factors moderate and/or mediate the connection between social relationships and recovery capital. Fifth, more research is needed to understand how these findings may be disseminated and implemented into existing recovery support infrastructure. Lastly, additional research is needed to compare this novel measure of recovery capital with existing measures of recovery capital (e.g., Assessment of Recovery Capital and Substance Use Recovery Evaluator).

- For policy makers: Findings from this study suggest that family and friends may be an important source of recovery capital for people in recovery. However, we know relatively little about why those who are married, living with children, and with particular friendship groups report more recovery strengths and fewer recovery barriers. This may be especially relevant because of the substantial treatment gap between those who receive professional treatment and those that do not despite needing it. Moreover, the recovery process does not end post treatment. Continuing care services and community recovery supports remain important for stable recovery. Future policies should include funding mechanisms for continuing and community recovery supports. There is also a significant need for research funding earmarked to investigate how and for whom specific types of social relationships may bolster recovery capital. Supportive policy and funding surrounding these social contexts will also increase individuals and organization’s ability to leverage these relationships for positive outcomes.

CITATIONS

Best, D., Sondhi, A., Brown, L., Nisic, M., Nagelhout, G. E., Martinelli, T., . . . & Vanderplasschen, W. (2021). The Strengths and Barriers Recovery Scale (SABRS): Relationships matter in building strengths and overcoming barriers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 663447. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663447