Study of recovery community organization participants over time shows peer-based recovery support activities are associated with modest improvement in recovery capital

Among their multiple functions, recovery community organizations deliver peer-based services to individuals in recovery, often via recovery community centers. Scientific research can help test whether these peer-based services help individuals navigate recovery challenges and reach recovery goals as intended. This study represents the first large-scale study to systematically collect electronic data from a national sample of recovery community organizations and to examine whether service utilization is associated with potential improvement in recovery capital over time.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Recovery community organizations are being widely implemented across the country to support individuals who use alcohol or other drugs, or who are in substance use disorder recovery, through advocacy, community outreach, and peer-based recovery services. Regarding their specific recovery support components, often delivered via recovery community centers, recovery community organizations are intended to help improve access to recovery resources and navigate day-to-day challenges (e.g., obtain and sustain employment, housing, healthcare, etc.) to build individuals’ recovery capital (i.e., all internal and external resources one can use towards recovery).

Despite recent widescale implementation of various supports through these recovery community organizations, not much is known about how these organizations facilitate recovery processes and whether their use of peer-based programming specifically improves certain markers of recovery or recovery capital. As well, not much is known about who is most likely to benefit from involvement with recovery community organizations and what factors may influence their involvement. This study represents the first large-scale study to systematically collect longitudinal electronic data from a national sample of recovery community organizations.

The researchers’ goal was to address several gaps of knowledge to improve programming and outreach efforts. First, they aimed to characterize participant populations engaged with recovery support services and assess their engagement patterns. The researchers also aimed to understand whether engagement in programs provided by recovery community organizations is associated with improvements in recovery capital and identify what aspects of this engagement predict changes in recovery capital. An understanding of all these factors may help to address barriers to access to recovery community organizations for those who need them but are not accessing them as well as improve tailoring of services for those who currently use them.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The research team conducted analysis of de-identified administrative data that was collected across 20 recovery community organizations who participated in the RecoveryLink electronic record platform from November 2019-October 2020. These recovery community organizations offered a variety of recovery support services, including direct peer services (e.g., peer engagement sessions or brief check-ins), resource referrals, pro-social events, advocacy activities, harm reduction services, mutual-help meetings, or other services, as well as providing recovery community centers in some areas.

The researchers examined changes between an individual’s intake (baseline) assessment and a second time-point when the assessment was given (operationalized as the current/most recent assessment). Across the 20 recovery communities, there were 3459 participants, but only 900 participants completed the recovery capital assessment at 2 time points. The researchers used the data from the 900 participants with two assessments in their analysis although the amount of time between these assessments varied between participants (on average, 106 days passed between assessments).

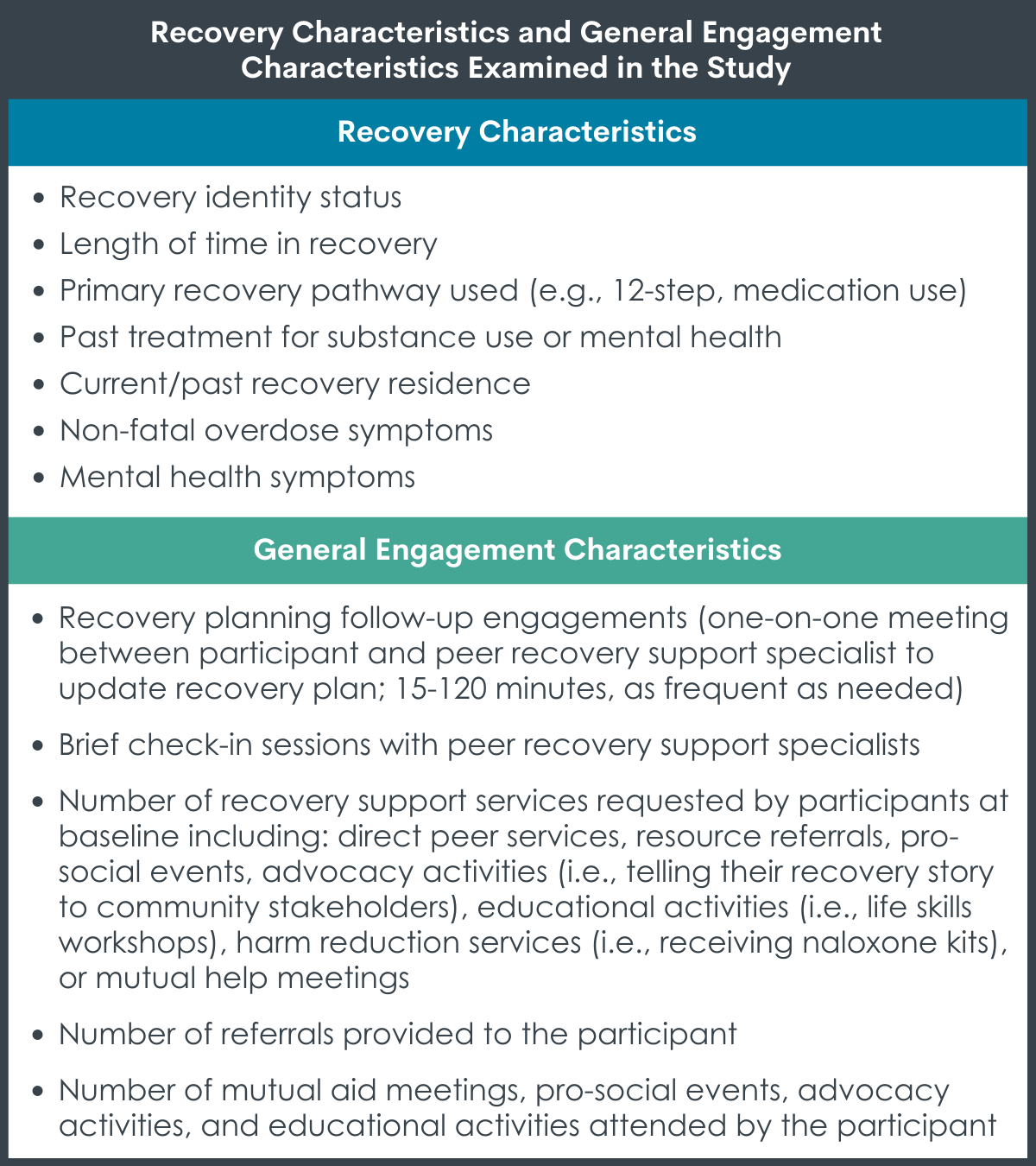

The three recovery-related outcomes of interest were (1) Recovery capital as measured by the Brief Assessment of Recovery Capital (BARC-10), (2) Recurrence of substance use, and (3) Number of emergency department visits. The Brief Assessment of Recovery Capital is a 10-item scale that creates a summary score of one’s level of recovery capital, where higher scores indicate higher levels of recovery capital: scores range from 0-60. Several additional variables were also collected as control variables for the analysis, including the following: demographics, recovery characteristics, and general engagement characteristics.

Recovery characteristics and general engagement characteristics examined in the study.

Of the total 3459 participants in the sample, about half were male (52.1%), and most were non-Hispanic (80.2%), and white (75.5%); average age of 39.98 years. The specific demographic characteristics of individuals in the analytic sample of 900 is not clear, but those with at least two assessments over time versus just one baseline assessment were more likely to be non-White, Hispanic/Spanish/Latinx, stably housed, employed part-time, have a vocational/tech degree, and identify as in recovery from a substance use disorder.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Individuals used the recovery resources from recovery community organizations in a variety of ways.

Of the full sample (i.e., all who engaged at least once in the recovery community organization), there were varying levels of engagement. Individuals most often requested direct peer services (79%) compared to mutual help meetings (51%), resource referrals (50%), pro-social events (36%), harm reduction services (24%) and other services (10%). On average participants spent about 130 days engaged in services and about 28 minutes per engagement.

Participants with at least two assessments improved on recovery capital and experienced low levels of substance use and emergency department visits between assessments.

On average, participants had a relatively high score of recovery capital at baseline: 48.30 out of a possible score of 60 on the BARC-10. Participants who had at least two assessments increased their overall recovery capital score on average by 1.33 points between those assessments, a small magnitude increase. Participants also experienced few returns to substance use (0.09 on average) and emergency department visits (0.02 on average) during the assessment period.

Level of recovery capital at intake strongly predicts later recovery capital gains.

When examining demographic characteristics and other functioning at intake, identifying as black (versus white), not receiving disability insurance, stable housing, and being on parole or probation were all associated with greater recovery capital at follow-up. For example, those with stable housing at intake had follow-up recovery capital scores 5.76 points greater than those who were not stably housed.

Receiving more recovery support services was associated with increased recovery capital, though effects were modest.

Controlling for demographic characteristics as well as recovery capital and other functioning variables at intake, follow-up engagement sessions and number of recovery plan goals completed were associated with recovery capital at follow-up. The magnitude of these relationships, however, were quite modest. For example, follow-up engagement sessions only accounted for 0.3% and recovery plan goals completed only accounted for 1% of an individual’s recovery capital score at follow-up, on average.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The researchers in this study analyzed administrative data collected via an electronic recovery record platform (similar to health records in clinical settings but focused documenting recovery support services) from 20 recovery community organizations in the United States. They found that this method of data collection may be a feasible way to collect and study recovery community organizations in the future. As well, the findings provide some support for the basic foundation of recovery capital theory, i.e., that some recovery capital is likely to lead to the generation of more recovery capital. Yet, participants started with relatively high levels of recovery capital, suggesting that they may have accessed the recovery community organization as a result of having some recovery capital. For example, their baseline scores were several points higher than a national sample of individuals who had recovered both in the past 5-years and 40-years. Thus, individuals with lower levels of recovery capital may be in need of more assertive linkage to help those with lower recovery capital access these services. These findings are similar to those of a study of new recovery community center participants attending centers across New England states that found that a minimal level of functioning and quality of life may be needed to begin to access these centers in the first place.

Among the sample which remained in the study for at least 2 assessments, gains in recovery capital were fairly small, with only a 1.33 average improvement, but low levels of substance use recurrence and emergency department visits suggest participation in recovery community centers may have helped sustain remission and reduce acute care service use across time. While the recovery capital measure is a useful, strengths-based measure of recovery outcomes, as a summary scale it may not reflect with the appropriate nuance all the important changes going on in one’s life in recovery.

The use of administrative data does not allow us to determine the effects for different types of recovery support resources and how these different types of resources could be implemented across settings. As the research team notes, “there is likely to be variations in the implementation of provided services across different organizations” especially given the fact that these were drawn from a national sample from different states in the US. While longitudinal studies on how individuals fare in recovery community organizations over time are just emerging, as the field matures, information on the nature of these peer support interactions, and what strategies provide the most benefit and for whom, will help to inform practice and policy. It seems likely that services with a particular support style (e.g., directive vs. motivational) and/or service content (e.g., direct linkages to community services vs. general social support) are the most helpful and training and adherence to these best practices could mobilize greater recovery capital changes, yet the evidence base cannot yet provide this information. Future research can help to investigate these more nuanced questions about the nature of recovery support service delivery in recovery community centers and organizations.

This study also raises several questions about the degree of service provision/usage needed to improve one’s level of recovery capital and other recovery outcomes. The fact that only 26% of the sample remained in the recovery community organization for at least 2 assessments is critical to informing future work. One interpretation could be that individuals who completed 2 visits versus those who did not needed those services and thus were more likely to stay engaged in the recovery community organization. Alternatively, the recovery community organization could have done such a good job linking individuals to services that the individuals only returned to the specific service they were linked to and not back to the recovery community organization for assessment; or individuals continued to use the services but did not want to do another assessment. Finally, individuals who did not have at least 2 assessments may not have felt that the recovery community organization served them well (e.g., perhaps they needed something aside from peer-based recovery services or perhaps they required peers with substance-specific training) and so did not continue use of the services. Because there were major differences between those who did/not complete the two assessments there could be selection bias of those who chose (or were able) to continued doing the assessments. Without additional follow-up among participants, the nuances of their continued (or lack of) participation will not be clear.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- There was a large amount of missing data: only 26% of participants had two assessments of recovery capital. There were major differences between those who did/not complete the two assessments suggesting there was potential selection bias of those who chose (or were able) to remain in the peer recovery support services. This could impact both the generalizability of the findings – whether these data are true for the population of individuals who engage with recovery community organizations or just this sub-set of individuals with 2 assessments (i.e., external validity). This could also impact how we interpret the research findings to guide future work in this area – that is, individuals who had 2 assessments and were included in the analyses may have had certain characteristics that enabled them to benefit from receiving recovery support services (i.e., internal validity).

- The timeline for assessment completion was not clear and the analysis did not address this limitation. Thus, there could be important differences between individuals across time, for example differences between individuals who remained in for a significantly longer period than others or differences for individuals with multiple assessment points, that would not be accounted for in these models that only used the baseline and most recent assessment point.

- The analysis used a progression of model testing, which may have missed variables that would only be identified as statistically significant when other key variables are in the model. As well, interactions between variables and site-level differences, e.g., such as the interaction of gender and recovery capital, were not explored or accounted for.

BOTTOM LINE

This research study analyzed data from 20 recovery community organizations in the United States, suggesting that this method of data collection may be a promising way to continue to collect and study recovery community organizations in the future. Participants who remained in the study for at least 2 assessment points maintained positive gains in substance use status and had lower levels of use of expensive acute care health services and also increased their overall level of recovery capital, suggesting their recovery process was improved during their recovery community organization involvement. Yet, recovery capital gains were quite modest, and there was a low retention of participants for even two assessment time points: more research is needed to understand what types of recovery community organization services are most helpful, and to whom, and the optimal ways to deliver such services.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: These findings highlight how peer-based recovery supports as provided by a recovery community organization could theoretically support one’s recovery process and improve their outcomes by linking them to helpful (and possibly free) resources in their communities. Changes can be slow and can occur in multiple domains of one’s life and at different times in the process; tailored linkages to a variety of services (e.g., mental health counseling, job skills training) and that are available in one’s close surroundings are vital. Connecting a loved one to a local recovery community organization may improve their access to recovery and other life supports; yet, it is important to note that our empirical understanding of these services is limited but growing.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Connecting individuals to supports and resources which address their most immediate needs is vital to building recovery capital and ensuring their continued motivation and success in recovery. Providers and systems should be part of the bridge that connects patients to needed services. By linking an individual to a recovery community organization, providers may help expand one’s recovery resource network beyond what the formal treatment system can offer. Yet, it is important for providers to understand the particular needs of their patient and whether a recovery community organization will provide the appropriate supports for that patient: there is a need to tailor these recommendations and supports to an individual patient’s needs as not all patients will benefit from the same type of programming and not all patients will choose to be fully engaged in recovery community organizations or benefit from such engagement.

- For scientists: More research is needed to better understand how length of engagement and use of specific services, as well as differences in recovery community organizations across geographic spaces, among various sub-groups of service users influences the recovery process. While this study demonstrated the potential utility of a large, national electronic database for collecting these data, future research may need to utilize a case study and/or qualitative approach for better understanding recovery capital changes in specific recovery community (or broader community) contexts as well as reducing barriers to ensure that these process and outcome data can be systematically collected.

- For policy makers: Comprehensive, systematic, and longitudinal research is needed to fully understand the exact mechanisms by which recovery community organizations can positively influence recovery trajectories and any barriers to their success as well as if peer-based recovery components are particularly useful tools in this regard. This study represents a first step in demonstrating that these data can be collected and synthesized from these organizations; funding to ensure that these practices can be rigorously studied and that, if found effective, can continue, should help improve these systems and enhance their sustainability.

CITATIONS

Ashford, R. D., Brown, A., Canode, B., Sledd, A., Potter, J. S., & Bergman, B. G. (2021). Peer-based recovery support services delivered at recovery community organizations: Predictors of improvements in individual recovery capital. Addictive Behaviors, 119, 106945. DOI: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106945

*Research features RRI personnel, but was reviewed independently for this Bulletin