How helpful is counseling for people bereaved through a substance-related death?

Those bereaved by a substance-related death face numerous factors that can impede the natural healing process. In this study, findings are summarized from interviews with people who relate their experiences with seeking help to deal with the loss of a loved one due to substance use. Results offer insight into the desired qualities of counselors and the still unmet needs of those who are bereaved.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

To date, the intersection of bereavement and addiction is an understudied area of clinical need. Statistics seeking to express the public health impact of alcohol and other substance use frequently cite the number of deaths attributable to substance use, implying to some degree that death is the ultimate and final outcome of problematic substance use. Left unsaid is the fact that such deaths are not the end for family and loved ones.

While the loss of a loved one is a natural, universally–experienced life event, it is also an intensely emotional and disruptive experience. In most cases, the experience of loss and its accompanying emotional upheaval attenuate gradually over time, particularly when the bereaved receives help from supportive companions. When losing a loved one to substance-related harm, however, this process can be complicated, as the death is typically premature, often sudden, and the bereaved may encounter disparaging comments about the deceased. It is more likely to encounter discussions seeking to attribute blame for the death than would occur when the death occurred due to a different type of accident or to natural causes.

To avoid such confrontational and painful experiences, it is not uncommon for mourners to misrepresent the circumstances surrounding the death of their loved one, thereby denying themselves the opportunity for support and validation, and undermining help-seeking behaviors. At the same time, those bereaved by a substance-related death are potentially at greater risk for developing complicated grief, an impairing form of grief that interferes with the healing process that affects approximately 7% of bereaved people in the general population. Risk factors for complicated grief include suddenness of death, death of a child, and experiencing other major life stressors, such as major financial hardships, all of which are common themes in substance-related deaths. Given this confluence of complicating factors in the experience of losing a loved one to substance-related harm, this study summarized results from interviews conducted with persons who self-identified as being bereaved through a substance-related death to shed light on how well currently–existing treatment modalities support those who experience the death of a loved one due to substance-related harm.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a UK-based qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with adults who experienced the loss of a loved one due to substance-related harm. Participants were recruited from the community via posters, emails, phone, social media, mutual–help groups, or referral from other research centers. Interviews were conducted by phone or Skype with a registered counselor with interest in substance-related bereavements. Within the interview, participants used a 1-10 scale to rate the quality of the support they had received during their bereavement. Otherwise, open-ended questions were used to explore to what extent the received counseling helped, what worked and what did not work, and what was needed/wanted but not attained. Qualitative data were coded using a technique called Iterative Categorization, which uses a 4-step iterative process to identify themes and patterns across interviews.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

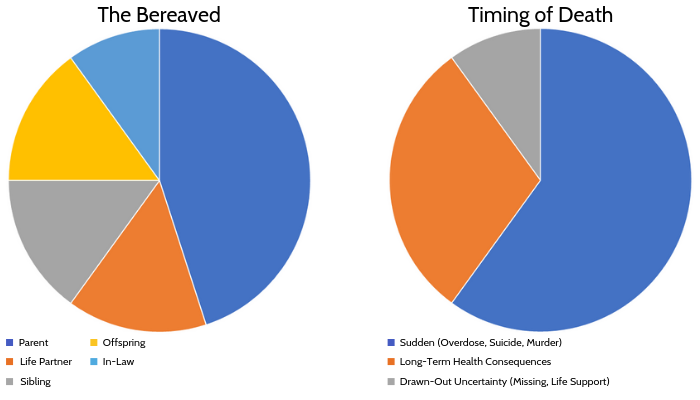

Participants were demographically diverse in age (29-71 years of age) and religion, but predominantly female (80%), middle class (100%), and White (70%). Most but not all knew that the deceased was engaged in problematic substance use prior to death (80%). Most commonly, participants were parents of the deceased (45%), though siblings, life partners, and offspring (15% each) were also represented. The deceased were predominantly male (90%) and 22-64 years of age when they died. A substantial proportion of the deaths were sudden (65%, overdose, suicide, murder, traffic fatality), though long-term health issues due to substance use also occurred (30%).

Figure 1. The frequency of the participants’ (n=20) type of relationship to the deceased and the suddenness with which the death occurred are depicted.

Regarding things that worked, participants reported valuing good referrals, and being able to start counseling when they were ready for it. In counseling, it was felt as helpful to be supported with the general aspects of grieving (e.g., validation, practical ways of coping, expressing emotions), and counselor characteristics were important to them (e.g., competent, having ethical boundaries, non-judgmental).

By contrast, participants felt it was unhelpful if the counselor lacked experience in bereavement and/or substance use, and if the counselor was tied to other areas of the participant’s life (e.g., workplace counselor). Group counseling was valued for providing the opportunity to share and bond with others with similar experiences, but difficulties in the group context included being subjected to stigmatizing comments, not fitting in (e.g., life partner in a group of parents), and joining too soon before being able to cope with hearing about others’ experiences. Participants also shared practices they did on their own that helped them, such as self-acceptance and compassion, positive reframing, and spiritual practices. They warned against critical self-talk, suppressing emotions, and internet searches. Unmet needs arose due to complexities surrounding the death: not understanding the deceased’s substance use, unresolved issues that arose due to the substance use (e.g., domestic violence), distressing circumstances of the death itself (e.g., suicide), experiencing anger, shame, or guilt evoked by encountered stigmatizing comments due to the deceased’s substance use, and coping with additional specific difficulties (e.g., an inquest).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study draws attention to the diversity and complexities of the experiences of those who have lost a loved one due to substance-related harm. To date, very little research has addressed the unique needs of this population, though it is likely quite large. Each year, hundreds of thousands of individuals die due to substance-related harm in the United States (several million worldwide), more so than due to traffic fatalities or suicides, and each death is estimated to leave behind 1-5 people with close attachments to the deceased. This study is one of the first to address substance-related bereavement. Complicated grief, the risk factors for which are common themes in substance-related deaths, has been a growing area of research in recent years, but within that growing field the additional complexities of substance-related deaths have not been addressed. The little research that has been done indicates that those who themselves engage in problematic substance use are at particularly high risk of developing complicated grief, adding to the urgency of this largely unmet area of clinical need.

Also of note is the large number of parents participating in this study (45%), particularly moms (35% of the total sample). Losing a child is a particularly painful experience, one that does not fall within the natural order of things. While it is not clear how well the prevalence of parents in this study generalizes to accurately describing the population of those affected by a substance-related death, parents losing their children is certainly a common theme in substance-related bereavement, and a known risk factor for complicated grief. Targeted support for this group of bereaved would be important to address. The downside of targeted support, however, is when it provides a barrier to participation for others. For example, a non-parent in a group of parents might feel isolated in a setting that is meant to provide connection and shared experience. Online mutual–help groups may offset this challenge somewhat, as online communities can draw on larger number of participants, and therefore are able to target increasingly specific groups of people. Even with this potential for highly–specific targeting, however, the reality is that every life – and death – story is unique and thus will never be matched in its entirety by those of others. This essential uniqueness, however, does not need to stand in the way of receiving and giving solace, companionship, validation, and support from those who also seek them and are willing to embark on this process with others.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As with most qualitative studies, the sample size was quite small, and thus it is unclear to what degree the observations made in this study generalize on a broader scale.

- Unlike most qualitative studies, only one person coded the qualitative data, and thus the coder’s personal biases are more likely to have influenced the presentation of the findings.

- The study was based in the U.K., which has quite a different culture and health-care support structure than other countries, including the U.S., and thus it is not clear how similar findings would be in a U.S. sample.

BOTTOM LINE

The experiences of those bereaved by a substance-related death are diverse and complex, representing an area of unmet clinical need.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The experiences shared by study participants may help highlight things that may be helpful during bereavement and warn against experiences and decisions that increase distress. For example, if one is considering one-on-one counseling, it may be helpful to consider ahead of time how the therapeutic frame of the counseling will be conducted (e.g., setting, times, durations, scheduling, fees), so as to prevent disappointment or distress if something is handled contrary to initial expectations. When considering group counseling, it may be useful to consider if it is more important to find a group most closely matching one’s own experience (e.g., a life partner group), which may be achieved through the use of online groups, or to find an in-person setting that may span more diverse experiences and in which participants discuss experiences more different than one own’s, but which would offer the immediacy of in-person connection and interaction.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This paper highlights some of the complexities and increased burden faced by those who suffer the loss of a loved one due to substance-related harm. They reinforce the value of being able to provide concrete and vetted referrals, and highlight some key issues that may be important to address when making referrals (e.g., when referring to support groups, addressing the readiness of the individual to hear others’ accounts of their own experiences, or to engage in a group who may use stigmatizing language).

- For scientists: The area of bereavement due to substance-related death is a vastly understudied area of research, given the number of substance-related deaths and the likely number of bereaved they leave behind, and the complex factors that typically surround these deaths. To what degree there is currently an unmet clinical need is not entirely clear. Larger-scale studies investigating the degree to which existing systems of care provide support for those bereaved through a substance-related death would be important to pinpoint unmet needs.

- For policy makers: There is an unmet training need for clinicians at the intersection of addiction and bereavement. The qualitative data presented in this study highlight how stigmatizing language, largely on the part of non-professionals encountered in help-seeking, but also by professionals (e.g., coming across as uncomfortable or not knowledgeable regarding addiction, actually using inappropriate terminology, etc.) increased the burden and distress experienced by this bereaved population. Minimal training and/or reminders on appropriate language and terminology, and basic understanding of addiction may go a long way to render existing systems of care more welcoming and supportive of those in need.

CITATIONS

Cartwright, P. (2019). How helpful is counselling for people bereaved through a substance-related death? Bereavement Care, 38(1), 23-32. doi: 10.1080/02682621.2019.1587869