Substance Use More Stigmatized Than Smoking Cigarettes and Obesity

Series: Breaking the Stigma

Studies have shown that people who use substances tend to be more highly stigmatized than other groups, and substance use is often attributed to moral failing rather than being recognized as a legitimate health condition. Stigma can even reduce help-seeking and act as a barrier to treatment and services

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

This study investigates this problem further by comparing people with substance use disorder (SUD) to those who smoke cigarettes or are obese to see which condition is most highly stigmatized. It also investigates if public opinion differs based on having an active disorder or one that is in remission.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

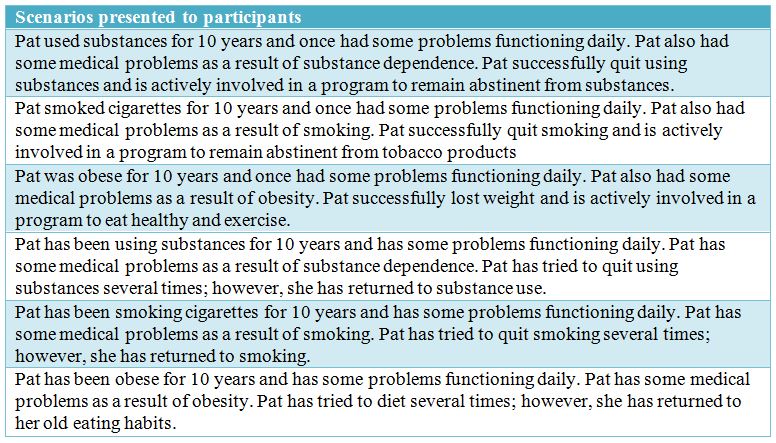

Phillips and Shaw conducted an online survey with a convenience sample of 161 adult participants aged 22 to 45. The sample was predominately female (83%) and White (84%). Each participant was assigned to read one vignette of a person with one of the following six conditions: current substance use, current smoking, current obesity, remitted substance use, remitted smoking, former obesity.

The scenarios are presented below:

Respondents then answered questions measuring social distance including how willing study participants were to allow the individual in the vignette to do each of the following: marry into their family, be their friend, socialize with them, work on a job, be a neighbor, and have their child date them. This scale was adapted from the Bogardus Social Distance Scale which measures how closely respondents want to associate with the individual. The questions increase in terms of closeness of this association with “marry into the family” representing the strongest association (lowest score).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

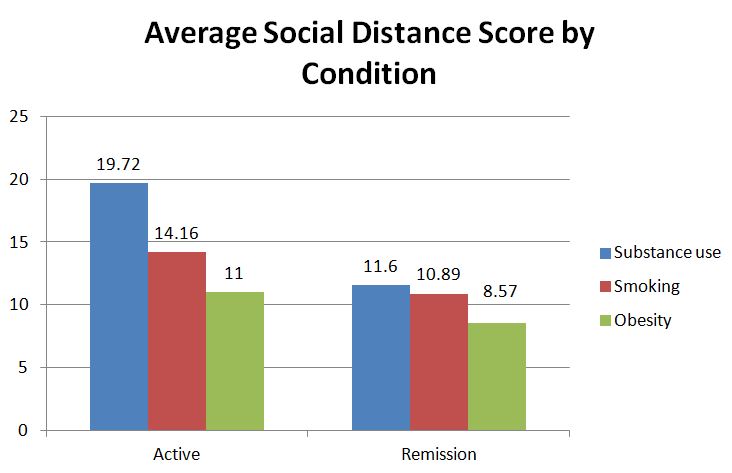

The authors used a summation of the social distance scores to determine level of social distance (which is how they measured stigmatization). Scores ranged from 7 to 28 with higher scores indicating higher desire to remain socially distant, and in turn, higher levels of stigma.

There were significant effects for the type of problem (i.e., substance use, smoking, or obesity) and for whether the condition was active or in remission. There was also a significant interaction between these two variables such that people with active substance use were significantly more stigmatized (i.e., received higher social distance score) than the other groups.

The groups are listed in order from most highly stigmatized to lowest level of stigma below:

- Active substance use

- Active smoking

- Remitted substance use

- Active obesity

- Remitted smoking

- Former obesity

While the remitted versions of all three conditions were less stigmatized than the active versions, this decrease in stigma was substantially less pronounced for individuals who use substances.

There is a need for interventions to reduce social distancing of current and former substance users as these attitudes perpetuate stigma and discrimination.

Faces & Voices of Recovery and Young People in Recovery are examples of organizations working to change public perceptions regarding addiction.

Also, one suggestion put forth by Kelly and colleagues is to remove substance abuse and abuser from our language about individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs). These terms evoke perceptions of SUD as a criminal or moral issue, rather than a disorder with biological, psychological, and environmental influences. In other words, terms like substance abuse may perpetuate stigma. In line with these studies, the International Society of Addiction Journal Editors released a statement against the use of stigmatizing language in the addiction field.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Prior research has shown that prescription opioid users may differ from heroin users in several ways that could have implications for treatment. For example, prescription opioid users tend to have shorter histories of use and fewer prior treatment episodes than heroin users. Studies also suggest that prescription opioid use may lead to heroin use and possibly injection drug use, so treating people who use prescription opioids earlier may prevent this progression.

This study supports past research suggesting that substance use is a highly stigmatized behavior which may have implications for treatment. Furthermore, even when remitted, stigmatizing attitudes towards individuals with substance use disorder (SUD) may remain. Whether this bias diminishes with time in recovery or ever goes away completely is unclear. This may mean, however, that individuals in recovery from a substance related condition may face further stigma and discrimination challenges even while maintaining remission over time.

Whether this bias diminishes with time in recovery or ever goes away completely is unclear. This may mean, however, that individuals in recovery from a substance related condition may face further stigma and discrimination challenges even while maintaining remission over time.

Even well-trained mental health clinicians are subject to the influence of language on stigma.

For example, when clinicians were surveyed about attitudes toward someone demonstrating substance problems in a vignette, those randomly assigned to the person described as a “substance abuser” were more likely to endorse personal culpability compared to those assigned to the person described as “having a substance use disorder” (see here).

There may be a need for education of service providers to decrease stigmatizing attitudes and help avoid inadvertent treatment disparities for patients who do have substance use disorders (SUDs).

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study has several limitations. The vignettes discussing the condition as remitted gave the character a female gender (e.g., Pat has tried to quit using substances several times; however, she has returned to substance use) while the active disorder vignettes kept Pat as a gender neutral character.

- Introducing a personal variable (gender) in one version of the vignette but not the other may impact how respondents answered the social distance questions.

- It is also unclear if the vignettes were randomly assigned. The study used of a sample of participants with limited diversity which has concerns for generalizability of results, and it is unclear where the study participants were drawn from.

NEXT STEPS

There is a lot of evidence supporting the notion that substance use is highly stigmatized.

Future research should focus on developing and testing ways to minimize or eradicate negative attitudes. It is also important to ensure that people with susbtance use disorders (SUDs) are able to seek help and stay in recovery without feeling the additional burden of discrimination and stigma.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study adds to the body of literature on the highly stigmatizing nature of substance use disorders (SUDs). Although remitted SUD evoked less social distance than an active addiction, stigmatizing attitudes remained high. Recovery support organizations like Young People in Recovery and Faces and Voices of Recovery and services like mutual help groups and recovery community centers can connect individuals who may share similar experiences.

- For scientists: While this study had limitations, the results were consistent with other studies on stigma and substance use disorder (SUD) that were conducted in nationally representative samples (see here and here) as well as internationally.

- For policy makers: Substance use disorder (SUD) and related conditions are among the top public health problems in the United States, contributing an estimated economic burden of around $700 billion annually. Many do not seek help because of fear of stigma and discrimination. Consider funding for research and programs that can address the public stigma surrounding SUDs.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: There may be value in becoming more aware of your own attitudes and behaviors toward your patients as negative perceptions may be affecting your work even if you are not aware of it (see here).

CITATIONS

Phillips, L. A. & Shaw, A. (2012). Substance use more stigmatized than smoking and obesity. Journal of Substance Use, 18(4), 247-253. doi: 10.3109/14659891.2012.661516