Supervised consumption site participation associated with reduced emergency department visits and hospitalizations

Supervised consumption sites are thought to reduce overdose deaths, prevent the spread of infectious diseases, and facilitate access to substance use disorder treatment. Rigorous research on whether and how these harm reduction services improve health outcomes can inform policy and practice. In this innovative study, researchers tested the effects of participating in an unsanctioned U.S. site on overdose and healthcare utilization over time.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

In the U.S., over 70,000 people died from drug overdose in 2019. Overdose deaths have further increased by 30% since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Supervised consumption sites are a harm reduction service thought to help reduce overdose deaths, prevent the spread of infectious diseases, and facilitate access to substance use treatment.

Supervised consumption sites provide a space for people to use drugs they bring to the site on their own with sterile equipment and under the supervision of trained staff. Staff are available to counsel people using the site, administer naloxone to reverse overdoses, and refer people to additional medical care services as needed. Supervised consumption sites exist in 13 countries worldwide. New York City opened the first sanctioned supervised consumption site in November 2021 and Rhode Island became the first U.S. state to pass legislation allowing supervised consumption sites.

Research shows that supervised consumption sites help people using them access medical and substance use treatment services, and are also correlated with reduced non-fatal overdoses and overdose deaths. However, research has only been conducted in a few communities, and grassroots’ advocacy supporting use of supervised consumption sites to address crises (e.g., HIV/AIDS and overdose epidemics) limits their rigorous evaluation in experimental or quasi-experimental research designs. This makes it difficult to evaluate if supervised consumption sites actually cause these better outcomes or if better outcomes could be explained by other factors, such as the community environment and availability of other harm reduction resources. In this study, the researchers tried to answer this difficult evaluation question by using a more innovative research and analysis design that examined the relationship between use of an unsanctioned supervised consumption site in the U.S. and medical outcomes (any overdose, skin and soft tissue infections, and emergency department utilization and hospitalizations).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The researchers followed 493 adults who inject drugs from the surrounding neighborhood of the unsanctioned supervised consumption site over 1 year (2018-2019). They interviewed participants initially, then again 6 months and 12 months later about their experiences of opioid-related overdose, any soft tissue infections or abscesses related to injection drug use, number of visits to the emergency room, and number of nights spent in the hospital over the previous 6 months. The researchers compared participants who had used the supervised consumption site to participants who did not on these medical outcomes across three 6-month periods: the 6 months before entering the study, the 6 months before the first follow-up, and the 6 months before the second follow-up.

Participants in this study were initially approached by outreach workers in the site’s surrounding neighborhood. Interested participants were given a card with the hours and location of a local community field site, where potential participants could talk privately with a study coordinator. To be included in the study, participants had to have injected illicit drugs in the past 30 days, be 18 years of age or older, and be willing and able to provide informed consent to participate.

Use of the unsanctioned supervised consumption site was by invitation only and invited individuals were asked not to disclose the existence of the site to others. Invitations were capped at 60 people to limit risk of disclosure and avoid drawing attention to the site among people in the neighborhood and law enforcement. If an individual stopped using the site, individuals who continued to use the site recommended new people to be invited, thus at any given time, about 50 people had invitations to the site.

Use of the site by participants was verified by staff at the site. Each time someone used drugs at the site, staff would record the date and a unique identifier based on non-identifying but easily reproducible information about the person. Those unique identifiers were also collected from participants as part of the study. The researchers matched participants’ information from the study to the supervised consumption site records to determine if and when study participants had utilized the site. Overdose deaths were verified by medical examiner records for participants who were lost to follow-up in the study (n = 111), using the same identification system.

All other clinical variables and outcomes were determined by self-report, including, in the past 6 months, how many times the participant experienced an opioid-related overdose, if they had an abscess or other soft tissue infection related to injection drug use, how many times they had gone to the emergency room to access healthcare, and how many nights they had spent in the hospital. Participants also provided by self-report their age, gender, race/ethnicity, diagnosis of psychiatric illness, income from illegal activities over the past 6 months, housing stability over the past 6 months, history and current participation in substance use treatment, and detailed information on the frequency and type of substance use over the past 30 days. The researchers also asked participants if they had used drugs in a bathroom of a social service agency over the past 6 months to assess the person’s familiarity with and trust in social service agencies. It is unclear from the information reported by the researchers how participants were asked about their psychiatric diagnoses, and it seems that only major depression, anxiety or bipolar disorder were recorded. Similarly, the researchers gave a limited description of how information on participants’ current and prior substance use treatment was gathered, and it seemed limited to methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone.

Before the researchers compared participants who had used the supervised consumption site (n = 59, 12%) to those who had not (n = 435, 88%), they controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, housing, recent drug use, recent alcohol use, past and current experience in substance use treatment, income from illegal activities, psychiatric illness, and service agency familiarity using a statistical technique that balanced the two groups on these characteristics.

As the participants in the two groups looked different across these characteristics, and these characteristics may also influence medical outcomes, balancing the two groups of participants as best they can on these demographic and clinical variables helps the researchers to isolate the effect of using the supervised consumption site on medical outcomes from the effects of these characteristics on medical outcomes. This technique helps to make a better case that using the supervised consumption site caused any observed differences in outcomes. Then the researchers calculated the probability or likelihood that a particular medical outcome (event) would occur (risk ratio/incident rate ratio) for each group (participants who had used/or been exposed to the supervised consumption site v. participants who had not).

Specific information about the nature of the individuals who participated in the study – for example, participants’ substance use behavior when they entered the study – was not provided by the research team to protect the privacy of participants and the unsanctioned (i.e., “illegal”) site.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Only a small group of participants used the supervised consumption site.

Fifty-nine (12%) of the 494 participants used the supervised consumption site at least once during the study. Those who used the site visited a median of 18 times across the previous 6 months. Over the course of the study, 111 participants were lost to follow-up. Of those, 13 died, including 11 who died from an opioid-involved overdose during the study. No one died at the site.

Site use was not associated with overdose or skin and soft tissue infections.

People using the supervised consumption site had a 24% lower risk of any overdose (fatal or non-fatal), 13% fewer overdose events, and a 14% greater risk of skin and soft tissue infections, but because these results were not statistically significant, we cannot say with certainty that supervised consumption site use actually reduces overdose risk or skin and soft tissue infections, increases them, or doesn’t affect them in the population because the estimates were too variable and unstable.

ED use and hospitalizations reduced.

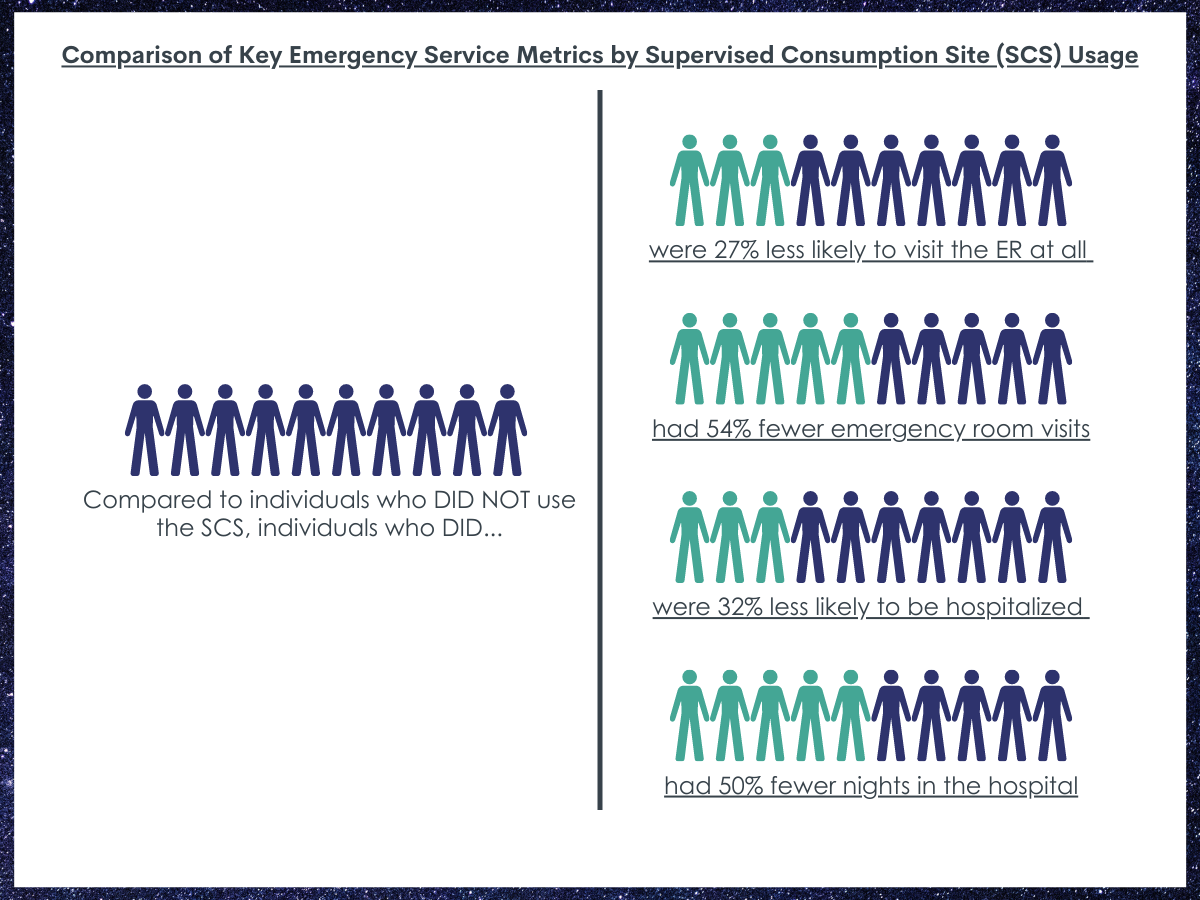

People who used the supervised consumption site were 27% less likely to visit the emergency room at all compared to people who did not use the site.

People who used the site had half as many (54% fewer) emergency room visits than people who did not use the supervised consumption site.

People who used the supervised consumption site were 32% less likely to be hospitalized compared to people who did not use the site.

People who used the supervised consumption site had half as many (50% fewer) nights in the hospital compared to people who did not use the site.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study suggests that use of an unsanctioned supervised consumption site in the U.S. is associated with reduced emergency room visits and hospitalizations. Emergency room visits and hospitalization could have been reduced by the supervised consumption site use in a couple of ways. For example, people using the site who experienced opioid-involved overdoses could be treated with naloxone and monitored at the site, preventing the need for an overdose-related emergency room visit. Additionally, staff at the site could have referred people using the site with skin and soft tissue infections to primary care before complications developed, reducing the need for emergency room visits and hospitalizations.

It is less clear if the use of a supervised consumption site is associated with reduced overdoses, overall, and reduced skin and soft tissue infections. If the supervised consumption site were sanctioned, and part of a larger recovery-oriented system of care at the community level, the site may offer greater facilitation of access to medical services and perhaps some on-site medical care, as is done in many supervised consumption sites globally.

Prior research on supervised consumption sites lacks causal evidence, meaning researchers aren’t as confident that they can say supervised consumption sites caused the outcomes they see because much previous research lacks rigorous research designs. Although the researchers in the current study still cannot be certain that supervised consumption site use caused these outcomes, the researchers use of sophisticated statistical techniques that balanced groups that used the site and those that did not on demographic and several clinical characteristics helps to make a better case that using the supervised consumption site was actually responsible for these differences in outcomes.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Only 12% of the sample (59 of 494 participants) used the unsanctioned supervised consumption site at all, and the average number of times a participant used the site over the study period was relatively low (median 18 times over a 6-month period). This likely reduced power to detect an effect of supervised consumption site use on overdose outcomes. As the researchers mention, it also limited their ability to test if more frequent use of the site was associated with better outcomes (a dose-response effect). No information was reported in the current study about why site use was so low. Other research suggests people who use drugs may be more likely to use a supervised consumption site when they are concerned about their supply content or when they don’t have access to other private spaces to use. On the other hand, they may be less likely to use a supervised consumption site because of concerns around criminalization and arrest, privacy, and confidentiality.

- Participants were not randomized to using the supervised consumption site like in a clinical treatment trial. Because of this, the researchers cannot say that the site caused these outcomes. However, the researchers used propensity score matching which helps make a better case that the changes in emergency room visits and hospitalizations were due to supervised consumption site use, rather than other factors.

- For several of the outcomes, participants were interviewed and asked to recall events over the past 6 months (self-report), which may lead to some recall bias or social desirability bias. The researchers were not able to verify non-fatal overdoses, emergency room visits, or hospitalizations with records (e.g., hospital records); however, they were able to verify supervised consumption site use and overdose deaths with records, which is a strength of the study.

BOTTOM LINE

This study found that, among 494 adults who inject drugs followed over a 12-month period, use of an unsanctioned supervised consumption site in the U.S. was related to lower levels of emergency room visits and hospitalizations, but not in reducing overdoses (fatal or non-fatal) or skin and soft tissue infections. However, participants who used the supervised consumption site did seem to show fewer overdose events (fatal and non-fatal) compared to those who did not use the site, but more research is needed to understand the true magnitude and reliability of this effect.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Use of a supervised consumption site was associated with reduced emergency department use and hospitalizations. This may be because supervised consumption sites can facilitate access to health care and administer life-saving medication during overdose, reducing the need for overdose related emergency room visits and hospitalizations. Use of supervised consumption sites may reduce preventable medical expenses. Although site use was not related to robust decreases in overdoses, these sites may reduce other harms, prevent disease, and provide other health care benefits. Read more about supervised consumption sites in the U.S.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Use of a supervised consumption site was associated with reduced emergency department use and hospitalizations. This may be because supervised consumption sites can facilitate access to primary care and administer life-saving medication during overdose, reducing the need for overdose related emergency room visits and hospitalizations. Use of supervised consumption sites may reduce preventable medical expenses. Supervised consumption sites have also been associated with facilitating access to mental health care and substance use treatment. If the supervised consumption site in the current study was legally permitted, there may have been more collaboration with medical services and mental health care. Although site use was not related to robust decreases in overdoses, these sites may reduce other harms, prevent disease, and provide other health care benefits. Future research on legal, sanctioned sites will help to determine if this ultimately the case. Read more about supervised consumption sites in the U.S.

- For scientists: Findings from this prospective, longitudinal cohort study using propensity score matching suggest that use of an unsanctioned supervised consumption site was associated with reduced emergency room visits and hospitalizations. Outcomes related to overdose (fatal and non-fatal) as well as skin and soft tissue infections were non-significant. Overall frequency of use of the supervised consumption site was low (on roughly just 10% of days over a 6-month period) and only 12% of the sample (N = 494) used the supervised consumption site at all, limiting the ability to test for dose-response effects. On the other hand, a strength of the study was its high retention rate (78% completed their 12-month visit) particularly in a sample of people who inject drugs likely experiencing many psychosocial challenges while participating in the study. Future longitudinal research could use similar retention methods. Additionally, prospective cohort or randomized controlled trial designs that have higher supervised consumption site utilization may offer more rigorous tests of the causal effects of supervised consumption site use on overdose rates and other medical outcomes. Also, more qualitative research is needed to understand why it is these services, when available, are utilized so infrequently and by so few individuals when given the opportunity.

- For policy makers: Use of a supervised consumption site was associated with reduced emergency department use and hospitalizations. This may be because supervised consumption sites can facilitate access to health care and administer life-saving medication during overdose, reducing the need for overdose related emergency room visits and hospitalizations. Use of supervised consumption sites may reduce preventable medical expenses. U.S. policy-makers have been hesitant to support legislation that would help implement supervised consumption sites for a host of reasons both scientific (e.g., insufficient research evidence) and political (e.g., the perception they may condone or increase illicit drug use). This is the first community-based cohort study evaluating the impact of an unsanctioned supervised consumption site on medical outcomes in the U.S. Although site use was not related to robust decreases in overdoses, these sites may reduce other harms, prevent disease, and provide other health care benefits. Supervised consumption sites might be an important component of a comprehensive approach to address injection drug use related medical harms and the resultant burden on the medical system. Read more about supervised consumption sites in the U.S.

CITATIONS

Lambdin, B. H., Davidson, P. J., Browne, E. N., Suen, L. W., Wenger, L. D., & Kral, A. H. (2022). Reduced Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalisation with Use of an Unsanctioned Safe Consumption Site for Injection Drug Use in the United States. Journal of general internal medicine, 1-8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07312-4