Tailoring Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder: Naltrexone may be best for reward drinkers

Precision medicine is an approach that can help tailor treatments to individuals based on unique characteristics of their condition. This study tested whether individuals with alcohol use disorder would respond better to FDA-approved medications depending on whether they drink “to feel good” or “to avoid feeling bad.”

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

When studies compare different medicines or psychosocial treatments for alcohol use disorder to each other, they often produce similar effects where none have a clear advantage. One explanation may be the substantial variability of individuals with alcohol use disorder; they vary in terms of the severity of their disorder, other medical and mental health conditions with which they are also diagnosed, and resources they have at their disposal (e.g., income, stable housing), to name just a few. The next important question becomes: For whom do these medications work best? This is also known as “precision medicine”; certain healthcare interventions may be better for some than for others and treatment should be tailored to these individuals more precisely. Because the FDA-approved alcohol use disorder medication, naltrexone, affects brain functioning associated with experiences of pleasure and reward (e.g., fun, excitement, euphoria) and the FDA-approved medication, acamprosate, is thought to affect brain functioning associated with relief (e.g., reducing stress, anxiety, depression), Mann and colleagues conducted a “precision medicine” type study to test if naltrexone actually is indeed more effective for individuals who drink for reward and whether acamprosate is actually more effective for individuals who drink for relief.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a secondary analysis of a primary, 12-week randomized controlled trial for alcohol use disorder (“alcohol dependence” in this study based on the 4th edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders) that compared 169 individual receiving daily oral naltrexone, 172 individuals receiving daily oral acamprosate, and 85 receiving a placebo medication. In addition to alcohol use disorder, to be included in the study, individuals were drinking in the month before the study at least 14 standard drinks per week for women and 21 for men. The study excluded individuals with history of other substance dependence (e.g., cannabis use disorder) and current psychiatric disorders such as major depressive or anxiety disorders. The primary study outcome was heavy drinking; that is, drinking five or more drinks in a day for men, or four or more for women. The average participant was 45 years old and 77 percent were male.

- READ MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

From a questionnaire assessing how frequently individuals drank in 15 “reward” situations (e.g., parties/celebration, having fun; out with friends and stopped by a bar) and 15 “relief” situations (e.g., feeling upset, feeling hopeless, criticized by others), authors used a sophisticated statistical procedure to create four groups of drinkers: 1) High Reward/High Relief; 2) High Reward/Low Relief; 3) Low Reward/High Relief; and 4) Low Reward/Low Relief. All analyses controlled statistically for gender, age, drinking severity, and smoking status, to isolate the effects of the medication on drinking outcomes – making a more compelling case that any group differences were caused by the medication and not by these other factors.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

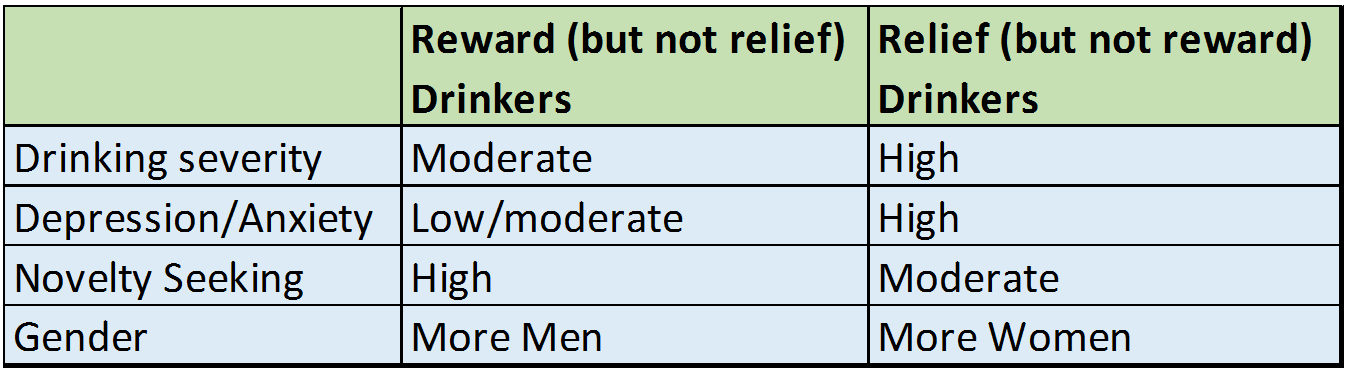

Individuals high in “reward” drinking and high in “relief” drinking had other characteristics that fit these profiles

For any heavy drinking, naltrexone was better than placebo for the reward drinkers, but acamprosate was no better than placebo for relief drinkers

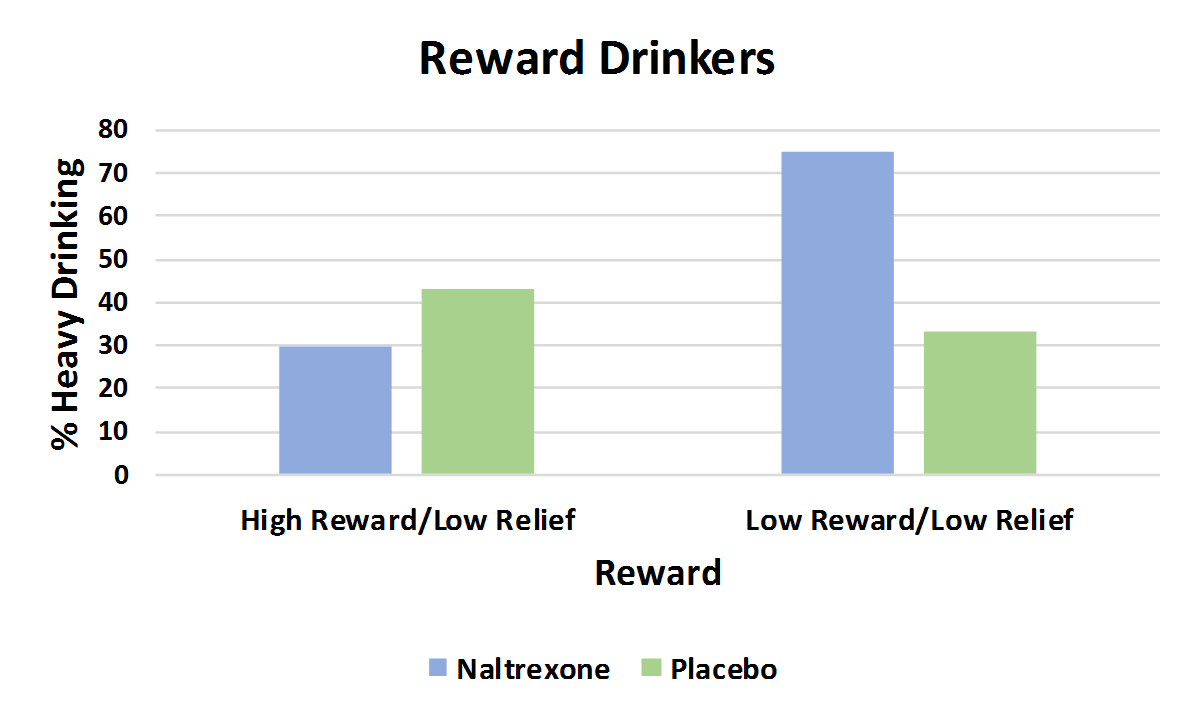

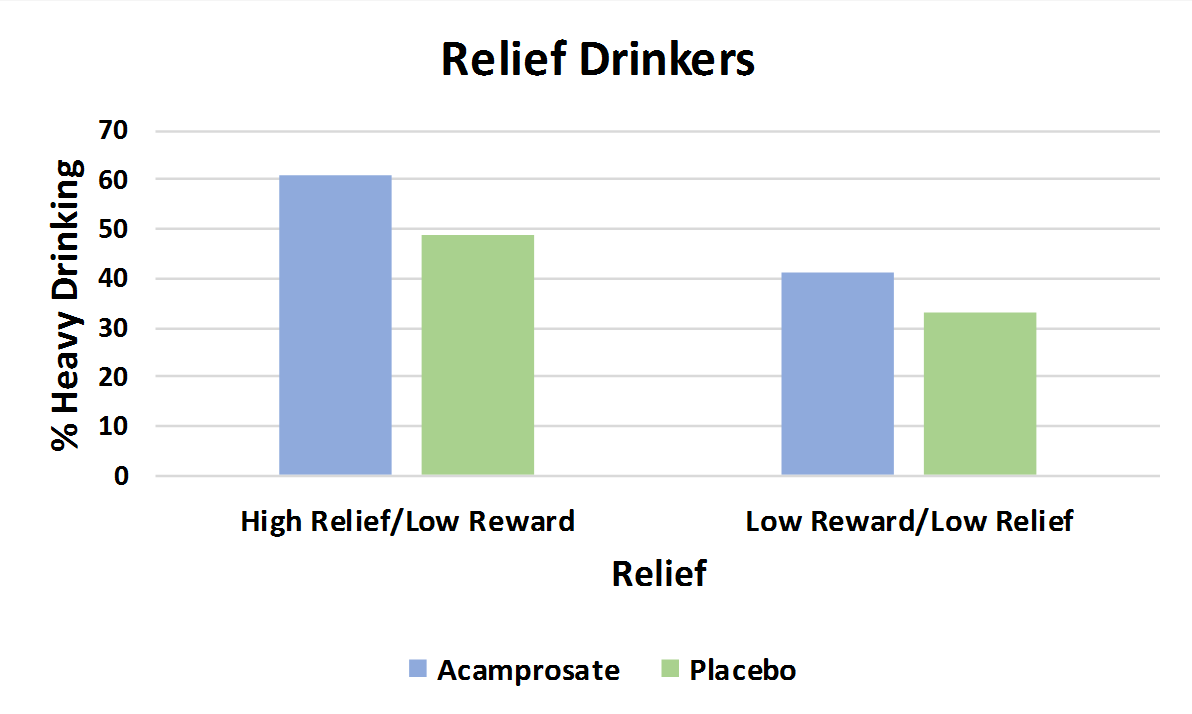

For reward drinkers (upper graph), naltrexone produced a 50 percent reduction in the likelihood of having a heavy drinking day compared to placebo, but had similar effects for drinkers who were low in both reward and relief drinking, as the authors hypothesized. For relief drinkers (lower graph), though, acamprosate participants had a similar percentage with any heavy drinking days compared to placebo; descriptively, they did a bit worse. In the graphs below, a shorter bar indicates fewer participants with a heavy drinking day, a better outcome (i.e., shorter is better than taller in these graphs.)

Outcomes were similar when examining time to a heavy drinking day as well

Authors also examined the number of days it took until an individual had a heavy drinking day (note: some made it the entire trial without a single heavy drinking day as described above, and they are counted as having made it 84 days, the length of the 12-week trial). Like the results for any heavy drinking day, for reward drinkers only, naltrexone outperformed placebo (72 days vs. 46 days to first heavy drinking day). For relief drinkers though, acamprosate again did no better than placebo.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Efforts at replicating observational findings where matching effects are initially identified in rigorous trials and effects are hypothesized ahead of time (i.e., “a priori”) have been largely unsuccessful to date. For example, in Project MATCH, a large randomized controlled trial comparing 12-step facilitation, motivational enhancement therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy, specifically looked at whether one treatment would be better than another for certain kinds of individuals. Although many of these treatment “matches” had been supported in smaller previous trials, very few matches were actually found. In another medication trial, authors did not find their hypothesized matching effect where they expected individuals with a gene variant (in the OPRM1 gene) to respond better to naltrexone, despite this being found after the fact in a previous study. In this initial study, authors found their hypothesized matching effect, that for reward drinkers, naltrexone may be a better medication for them than acamprosate.

Importantly, if this study’s findings are replicated, based on the types of measures used, treatment programs and other health care providers may be able to identify reward drinkers because reward/relief drinking was assessed using an easy-to-administer questionnaire. Although in this study, reward drinkers only did better on naltrexone compared to those who were neither reward or relief drinkers, separate analyses relevant to clinical settings showed individuals did better on naltrexone too when, on the drinker-type questionnaire, reward scores were greater than relief scores and the reward score is between 12-31. Such a distinction is easy to make in health care settings and could be applied in a straightforward manner.

While authors speculate that acamprosate may indeed be better for relief drinkers if they enter treatment with just a few abstinent days or less (rather than several days or more as was the case in this study), this would need to be tested scientifically. Also, the study examined oral daily dosing of naltrexone; it will be important to assess whether there are similar matching effects from extended release/once per month injectable formulations of naltrexone (also known by its brand name Vivitrol). There are lots of caveats to these findings (see below), and replications to confirm these findings are needed in other samples before being clinically recommended. There is much more to be learned about whether, and how, to match individuals to specific treatments before systematic precision medicine approaches can be undertaken. That said, the model by which authors developed and tested theoretically-driven matching hypotheses to inform a precision medicine approach is one that can be applied in other studies of substance use disorder medication and psychosocial interventions.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- To be included in the study, individuals needed to have a diagnosis of alcohol dependence but no other current substance dependence (consistent with moderate/severe substance use disorder) or psychiatric disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder or anxiety disorders), two weeks of alcohol detoxification and three days or more of abstinence. This is a narrowly defined group of individuals, and their findings may not hold up in individuals with a more complex set of presenting problems.

- All participants received “medication management”, a brief, regular psychosocial intervention that is often paired with medications in randomized controlled trials like this one. The effects of the medication itself cannot be teased apart from any benefits individuals derive from clinical care, monitoring, and advice from a health care professional received as part of medication management.

- The advantage of naltrexone compared to placebo for reward drinkers occurred during the 12-week medication trial. Whether this advantage would persist if the medication were continued over a longer period cannot be determined by these study findings.

- Reward drinkers were more likely to be male than female and it is unclear whether these findings are true for both women and men – if female reward drinkers benefit from naltrexone. In fact, a recent meta-analysis for example, found that women benefited very little if at all from naltrexone compared to men. This hopefully will be examined in future research again, to enhance the precision of the treatment approach.

- The study did not consider liver functioning as an additional “precision medicine” variable. Because acamprosate is metabolized by the kidneys and naltrexone is metabolized via the liver, for those with significant liver disease, acamprosate may need to be used regardless of whether the patient may be a reward or relief type of drinker.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Efforts are underway to help tailor alcohol use disorder treatments to individuals. While very little is known to date about characteristics that might indicate an individual will respond better to one alcohol use disorder treatment or another, in this study authors found that those who drink more for alcohol’s emotional rewarding effects (e.g., to have fun, to celebrate, etc.) might respond better to the FDA-approved medication naltrexone compared to acamprosate. Given that this study excluded individuals with any other substance use or psychiatric disorders, however, the results may not apply to most individuals. That said, if your drinking patterns adhere more to “reward”-type drinking, naltrexone may be a better first choice if you are considering medications with your health care team.

- For scientists: This study was a laudable precision medicine-based effort to identify endophenotypes among individuals with alcohol use disorder that might indicate better response to naltrexone or acamprosate. While authors hypothesized a priori that reward drinkers would respond better to naltrexone, and relief drinkers would respond better to acamprosate, only the reward-naltrexone hypothesis was supported. While the results are promising, findings need to be replicated in other samples. The model by which authors developed and tested theoretically-driven matching hypotheses to inform a precision medicine approach is compelling and one that can be applied in other studies of substance use disorder medication and psychosocial interventions.

- For policy makers: Efforts are underway to help tailor alcohol use disorder treatments to individuals. While very little is known to date about characteristics that might indicate an individual will respond better to one alcohol use disorder treatment or another, in this study authors found that those who drink more for their emotional rewarding effects (e.g., to have fun, to celebrate, etc.) might respond better to the FDA-approved medication naltrexone compared to acamprosate. Given that this study excluded individuals with any other substance use or psychiatric disorder, however, the results may not apply to many individuals. Precision medicine is a budding sub-field within addiction treatment and recovery science, and there is much that can be gleaned from precision medicine already being implemented in other fields like oncology. More attention and funding for projects such as the one reviewed here may lead to more effective tailoring of treatments to individuals and ultimately to enhanced health outcomes.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Efforts are underway to help tailor alcohol use disorder treatments to individuals. While very little is known to date about characteristics that might indicate an individual will respond better to one alcohol use disorder treatment or another, in this study authors found that those who drink more for their emotional rewarding effects (e.g., to have fun, to celebrate, etc.) might respond better to the FDA-approved medication naltrexone compared to acamprosate. Identifying reward drinkers using the method in this study is relatively straightforward, only requiring a 30-item self-report questionnaire. Given that this study excluded individuals with any other substance use or psychiatric disorders, however, the results may not apply to the majority of patients with alcohol use disorder. Other factors that may further influence these findings is the patients’ sex and liver functioning. That said, if a patient’s drinking patterns adhere more to “reward”-type drinking, in general, naltrexone may be your first consideration.

CITATIONS

Mann, K., Roos, C. R., Hoffmann, S., Nakovics, H., Lemenager, T., Heinz, A., & Witkiewitz, K. (2018). Precision Medicine in Alcohol Dependence: A Controlled Trial Testing Pharmacotherapy Response Among Reward and Relief Drinking Phenotypes. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(4), 891-899. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.282