Genes and teens: How is youth cannabis use influenced by genetic risk and peer use?

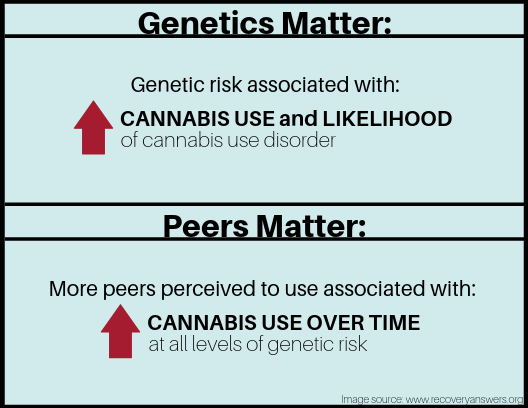

Genetic and environmental contributors (e.g., peer cannabis use) to the course of an individual’s cannabis use are well documented. However, it is not known how these factors interact to influence the extent of cannabis use over time in youth. This study found that both genetic propensity to use cannabis as well as peer involvement with cannabis use were important contributors to the change in youth cannabis use over time.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

It has become increasingly important to identify the factors that predict which teens become heavy cannabis users, particularly as more states move toward cannabis legalization and barriers to access decrease as a result. It is well known that persistent, heavy cannabis use has a component that is accounted for by genetics (i.e., it is heritable). That is, an individual’s genetic make-up has a sizable influence on whether someone will use cannabis heavily and over a long period of time. Additionally, affiliation with peers who are perceived to be cannabis users (regardless of their actual level of use) is cited as one of the most robust predictors of cannabis and other substance involvement. In moving toward understanding how these two strong and reliable predictors (i.e., genetic risk for cannabis use and perceived peer cannabis use) interact to influence youth cannabis use over time, Johnson and colleagues studied a cohort of over 1,000 individuals between the ages of 12 and 26 years from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA). The ultimate goal of this research study was to define the independent and shared influences of genetics and perceived peer environment on risk for cannabis use escalation during adolescence and young adulthood.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Study authors examined 1,167 children of individuals recruited for the COGA in seven sites throughout the United States. More than 60% of participants had at least one parent with an alcohol use disorder. Participants were between the ages of 12 and 26 years at their initial assessment, were assessed every two years, and had at least three separate assessments (i.e., data collection waves). Additionally, all participants were of white and European ancestry, which is a common practice in genetic studies due to ancestral differences in how genes relate to biological outcomes. (Check this article out for more information on the methods behind genetic research, and this article for problems associated with a limited diversity in genomic science).

At every time point, participants reported on their lifetime cannabis use (yes or no), frequency of past 12-month cannabis use in days which was converted to an interval (e.g., 0-20 days in the past year), maximum lifetime cannabis use frequency in a 12-month period, cannabis use disorder based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5), and perceived peer cannabis use while high school-aged (i.e., 12-17 years) where they indicated whether none, a few, or most/all of their peers used cannabis. Of note, while the DSM-5 typically requires that two or more substance use disorder symptoms are met in a 12-month period in order to be diagnosed, this study considered an individual having met criteria for cannabis use disorder if they experienced two or more symptoms at any point in their life. Additionally, a “polygenic” risk score for cannabis use was constructed for each individual, which is a method of aggregating the cumulative amount of genetic risk an individual possesses across the entire genome. Genes that were accounted for in this risk score serve a variety of functions, such as guiding the formation of new neurons during development, and transmission of the neurotransmitter most often implicated in the experience of “rewarding” feelings, dopamine, which may together increase risk for heavy cannabis use.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Genetic risk was associated with hazardous or heavy cannabis use.

Greater genetic risk for cannabis use was associated with lifetime history of cannabis use disorder, as well as patterns of cannabis use over time. That is, individuals with greater genetic liability for cannabis use were more likely to meet DSM-5 criteria for a cannabis use disorder and were more likely to use persistently at high levels across the course of the study. More specifically, increasing genetic liability for cannabis use was associated with a 1.4-times increased chance of using cannabis at high levels.

Level of peer cannabis use was also critical in separating light from heavy cannabis users.

Having more peers that were perceived to use cannabis was associated with higher levels of cannabis over time, and this factor was nearly 4-times more important in understanding patterns of cannabis use than genetic risk. Further, perceived peer cannabis use predicted cannabis involvement at all levels of genetic risk.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study builds upon prior work to define the factors that contribute to progression of cannabis use. This has become increasingly important as cannabis becomes more widely available due to legalization and commercialization. Although this study highlights the importance of both genetics and environment in predicting who will and who will not increase in cannabis use over time, the findings especially stress the importance of perceived peer cannabis use in understanding use patterns over time. This is in line with other studies that show that environmental factors like peer use tend to explain more of the variance in substance use during early adolescence, whereas genetic influences become more important as individuals transition into young adulthood.

Other studies have shown that perceived normative peer behaviors are key predictors of a multitude of health behaviors, but also that individuals are often not accurate in estimating actual behavior of their peers. Some studies have found that perceived peer use is more predictive of an adolescent’s level of cannabis use than actual peer use. Therefore, and particularly in light of the findings reviewed here that perceived peer cannabis use is highly predictive of youth cannabis use over time, it is highly plausible that normative misperceptions may be a powerful area for intervention. More specifically, educational efforts designed to disseminate knowledge that most teens do not, in fact, use cannabis may represent a potent prevention strategy. Studies that develop and test strategies that target entire peer groups in real-time could also help address this effect of greater perceived peer use on hazardous and heavy use.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- All analyses were restricted to white individuals of European ancestry. Therefore, it is not known whether findings will replicate to other populations.

- Perceptions of peer cannabis use were only assessed when participants were high school-aged. It is not known whether perceived peer cannabis use at later time frames (e.g., during young adulthood) have a similar influence on behavior.

- Only perceptions of peer cannabis use were measured. It is not known whether actual peer cannabis use had a similar impact on behavior. However, other studies have found perceptions of peer use to be a reliable proxy of actual peer use and, in some cases, may actually be more predictive of an adolescent’s level of cannabis use.

- Perceived peer use of other substances was not controlled for in these analyses. Therefore, it is not known whether the effects observed are specific to perceptions of cannabis use specifically, or substance use more generally.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study demonstrated that the influences on cannabis use behavior are complex and multi-faceted. While some are not possible to change (e.g., genetics), many can be addressed. Findings strongly suggest that affiliating with peers that are not perceived to be using cannabis can have a potent positive influence on an individual’s own substance use behavior. The findings here are consistent with studies of how substance use disorder treatment works, which often highlights the importance of adding individuals to one’s social network that support recovery and other healthy behavior and dropping those who are heavy drinkers and/or drug users.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Findings implicate not only genes, but also peer environments as important factors in understanding risk for cannabis use patterns over time. Therefore, it remains critically important to view the treatment-seeking individual within the context of his/her environment. Reducing affiliation with substance using peers is a powerful target for both prevention and treatment, as is correcting and re-structuring misperceptions surrounding normative behavior that might implicitly and/or explicitly impact health behavior.

- For scientists: Findings point to a unique role of both polygenic liability for cannabis use and perceived peer cannabis involvement in trajectories of cannabis use among adolescents. Though not directly tested in this study, findings also implicate objective peer affiliations as an important environmental risk factor for individual substance use, as other studies have found global peer perceptions about cannabis use to be closely correlated with actual cannabis use among close friends. The study represents an important step in developing a dynamic psycho-biological model for understanding risk for substance use over time. Future studies are needed that incorporate other environmental and biological agents of risk in order to develop a deeper mechanistic understanding of substance use progression as well as more precise targets for intervention.

- For policy makers: Findings implicate both genetic risk for cannabis use as well as perceived level of cannabis involvement in peers as independent, robust predictors of cannabis use in teens. Given that recent data from the Monitoring the Future Survey suggest that most teens do NOT use cannabis, efforts to correct the widespread inaccurate notion of cannabis use ubiquity may have important implications for use at a population-level. Such efforts can be done at an individual-level, but effects may be more pronounced with widespread campaigns to correct false beliefs on social norms as has been done by others in the context of alcohol. Further, the field would greatly benefit from continued, widespread funding for research on cannabis use in youth, given that barriers to cannabis use continue to decrease as legal recreational cannabis markets become more ubiquitous.

CITATIONS

Johnson, E. C., Tillman, R., Aliev, F., Meyers, J. L., Salvatore, J. E., Anokhin, A. P., . . . Agrawal, A. (2019). Exploring the relationship between polygenic risk for cannabis use, peer cannabis use and the longitudinal course of cannabis involvement. Addiction, 114(4), 687-697. doi: 10.1111/add.14512