How does topiramate work for alcohol use disorder? A look at the effects on brain activation in response to alcohol cues and relationship to alcohol craving and use

Topiramate is an anti-seizure medication that has been recently investigated for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Though not yet approved by the FDA for this purpose, topiramate shows promise for reducing heavy drinking and craving, and promoting abstinence. Investigating brain changes that occur in response to topiramate can provide insight into how the medication works and its utility in alcohol use disorder treatment and recovery. In this study, the researchers examined the effects of topiramate on brain responses to alcohol cues and their relationship to craving and heavy drinking among individuals with alcohol use disorder.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Alcohol-related cues (e.g., visual cues like a beer bottle, a bar, etc.) can play a role in ongoing alcohol use and a return to alcohol use after a period of abstinence. Brain imaging studies show that individuals with alcohol use disorder have enhanced dopamine release (brain chemical that plays a role in pleasure and reward) and brain activation in regions involved in reward processing (e.g., an area called the ventral striatum) when exposed to alcohol-related cues. Topiramate is an anti-seizure medication that was traditionally prescribed to people for epilepsy and has more recently been investigated for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Though not yet approved by the FDA, emerging studies suggest that topiramate may be a promising treatment for alcohol use disorder and some currently use it as an off-label treatment for this purpose. More specifically, topiramate has been shown to reduce heavy drinking – defined differently across studies but indicative of consumption of multiple drinks in a way that increase risk for harm – and/or craving and promote abstinence in clinical trials conducted to date. Also, preliminary work suggests its efficacy may be somewhat greater than that of naltrexone and acamprosate (i.e., the most commonly prescribed medications for alcohol use disorder treatment).

Little research has been conducted to evaluate the brain changes that underlie topiramate’s effects in alcohol use disorder populations. Characterizing topiramate’s effects on the brain and its relationship to behavior may help further our understanding of how this medication, traditionally used for epilepsy, works for alcohol use disorder to address maladaptive alcohol-related behaviors, which can ultimately guide decisions around FDA approval of topiramate for alcohol use disorder or the development of new drugs with similar neural targets. It has been hypothesized that topiramate may work by reducing dopamine release in reward-related regions of the brain when alcohol is consumed, or individuals are exposed to alcohol cues. Over time, this decrease in the brain’s response to alcohol might act to decrease the reinforcing/rewarding effects of alcohol, thereby weakening the learned association between alcohol, alcohol cues, and reward, and reducing alcohol cravings and the motivation to drink. Decreased reward from alcohol and alcohol-related cues (e.g., liquor bottle, bar, alcohol advertisement), in turn, means less drinking over time and fewer negative consequences. To test this hypothesis and better understand how topiramate works, this study examined the effects of topiramate on brain responses to alcohol cues and their relationship to craving and heavy drinking among individuals with alcohol use disorder.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors conducted this brain imaging investigation as part of a larger double-blind randomized controlled trial, to evaluate topiramate’s effects on craving, heavy drinking, and the brain’s response to alcohol cues among individuals with alcohol use disorder. Participants were randomized to receive either (1) topiramate (n = 12) at a maximal daily dosage of 200 mg per day or (2) a placebo (n = 8).

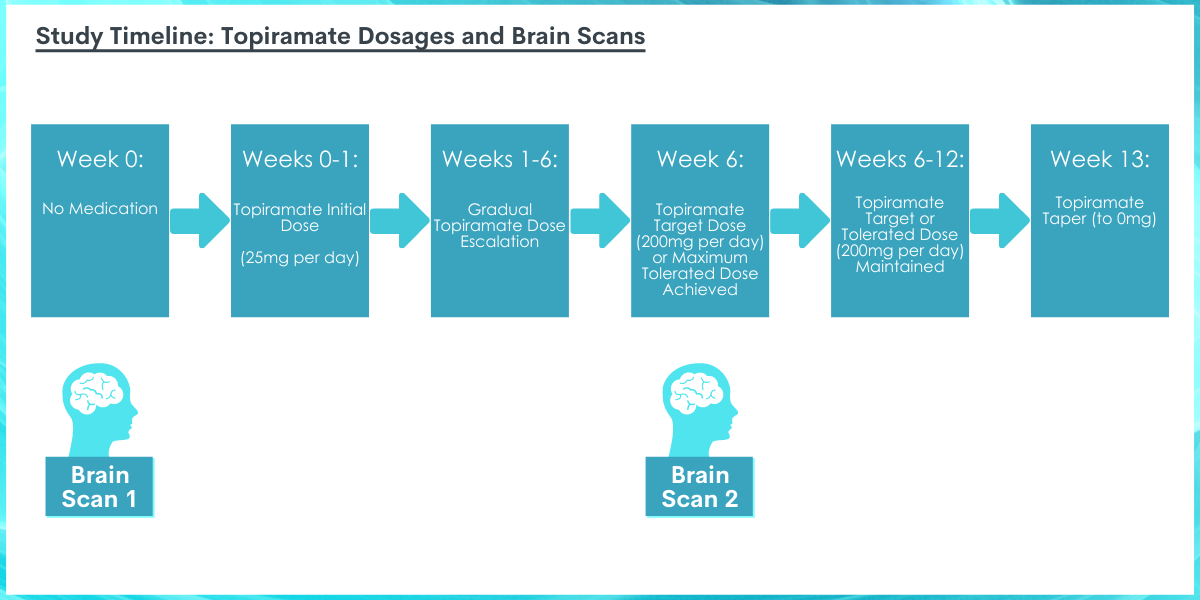

All participants completed brain scans on two occasions. Brain scans were completed before starting medication (i.e., baseline) and after about six weeks of topiramate or placebo treatment (i.e., after the medication was increased to the maximal tolerated topiramate dose, up to 200 mg per day, and maintained at that dose for one week; average = 6.65 weeks after starting medication). Participants were instructed to not drink alcohol on the night before their brain scan and the absence of recent alcohol use was confirmed with a breathalyzer. Brain scans were performed with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which produces detailed images of the brain and allows for the measurement of brain activity in specific brain regions. The researchers measured cerebral blood flow, an indirect measure of blood supply to different parts of the brain, reflecting brain activity. During both imaging visits, participants completed a control-condition fMRI scan followed by an alcohol cue-reactivity fMRI scan. The cue-reactivity condition required participants to view a video in which individuals were consuming alcohol and using language that was intentionally meant to induce a desire for alcohol use. The control condition video was similar but did not display alcohol use or any other alcohol-related content. The control condition fMRI data was used to account for individual differences in general brain activity so that the researchers could observe brain activation specific to alcohol cues. After isolating brain responses to alcohol cues, the researchers calculated differences in brain activation from baseline (pre-medication) to 6-week follow-up and assessed whether these measures of change in brain activity differed between the topiramate and placebo groups. They expected participants receiving topiramate to show reduced levels of activation compared to the placebo group in response to the alcohol cues over time. Participants also completed self-reported ratings of alcohol craving before and after watching each video and reported on the number days on which they drank heavily (defined as ≥ 5 drinks per day for men & ≥ 4 drinks per day for women) in the week prior to each fMRI scan.

Participants started their medication on the evening following their first brain scan. Participants assigned to the topiramate group received 25 mg of topiramate per day for one week. Thereafter, the dose was gradually increased every week until week 6, when the maximum tolerated dose was reached (i.e., target dose of 100 mg twice daily). The maximum tolerated dose was maintained during weeks 6 to 12. At the end of the study, patients were then tapered off of the medication.

The placebo group received a visually identical but inactive set of pills. The patients and researchers were blind to medication assignment (i.e., unaware of whether they received the placebo or topiramate). One-third of patients (n = 4) could not tolerate topiramate at escalated doses and were therefore maintained on lower doses, meaning they did not reach the maximal target dose (200 mg) by the time of the second brain scan. Nonetheless, these patients were included in the analyses. Both the topiramate and placebo groups had relatively high medication adherence between brain scans, with an average of 6.8 and 7 days of medication use per week, respectively.

All participants were diagnosed with a current alcohol use disorder based on the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (fifth edition, or DSM-5), reported drinking an average of ≥ 24 (men) or ≥ 18 (women) standard drinks per week, and expressed a desire to stop or reduce their drinking. On average, participants were males (70%), ages 45 to 50 years, with 17 years of education. All participants were of self-identified European descent. At baseline, participants reported an average of about 25 drinking days, 6 drinks on an average drinking day, and 19 heavy drinking days during the past month. Groups did not differ in demographics or recent drinking behaviors at baseline.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Topiramate patients had larger reductions in brain activation in response to alcohol cues.

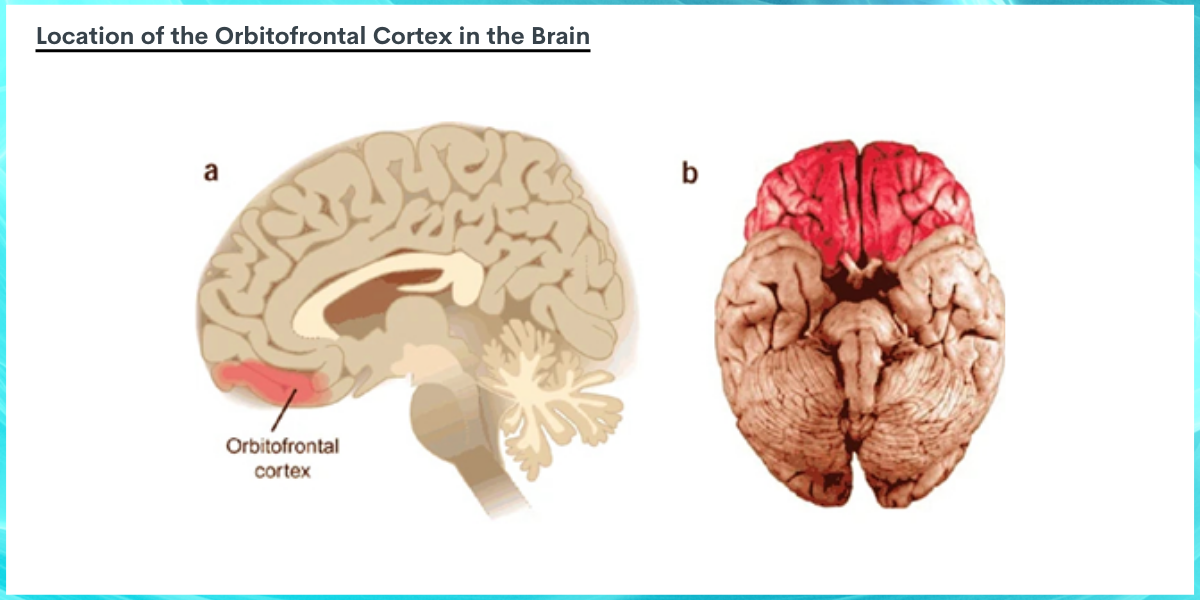

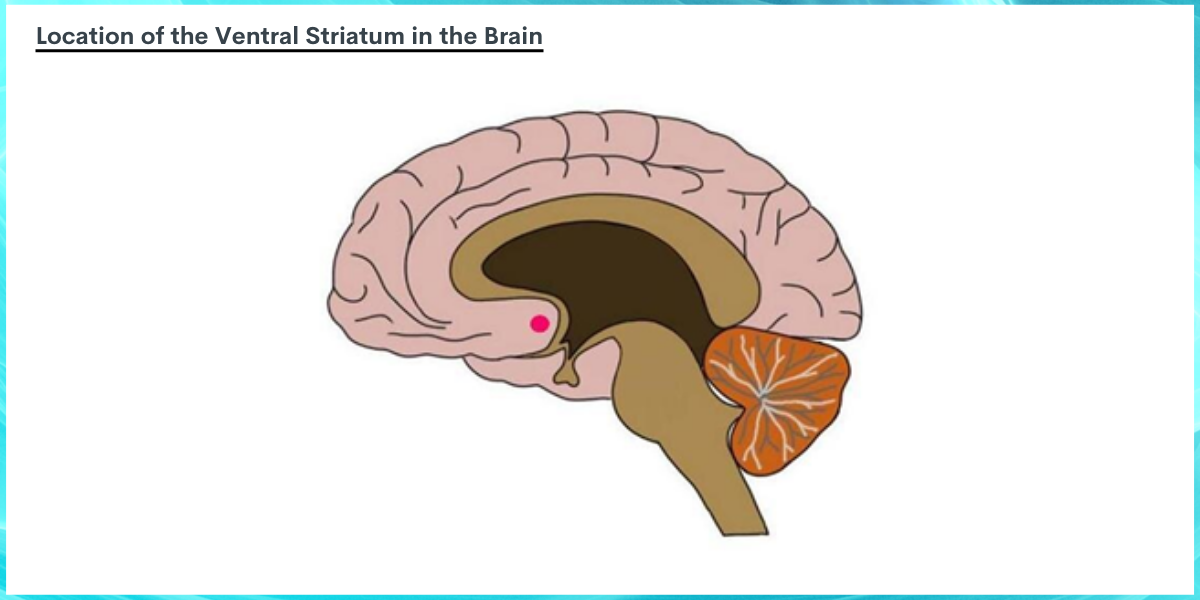

Compared to the placebo group, the topiramate group showed greater reductions in brain activation in response to alcohol cues after 6 weeks of treatment. Reduced responsiveness was seen among topiramate patients in an area associated with decision making and reward-related behavior called the ventral striatum and an area associated with sensory integration and learning/decision-making for emotion and reward-related behavior called the orbitofrontal cortex.

Image source: Wallis, 2006. The image above depicts the location of the orbitofrontal cortex in the brain in red. Image A is a sagittal section of the brain (as if someone were facing with their forehead pointed toward the left, and the brain were cut in half from forehead to the back the head), with the orbitofrontal cortex located near the forehead, or left side of the image. A much greater surface area of the orbitofrontal cortex can be seen when viewing the underside of the whole brain in figure B, where the front of the brain closest to the forehead is portrayed at the top of the image, and the back of the brain portrayed at the bottom of the image.

Six weeks of topiramate treatment resulted in greater reductions in craving after exposure to alcohol cues, as well as a greater reduction in heavy drinking days.

When compared to placebo participants, topiramate participants had greater reductions in self-reported craving after viewing alcohol-related cues at 6-week follow-up. When the researchers evaluated heavy drinking days in the week prior to baseline and follow-up scans, they found that the topiramate patients reported a larger reduction in heavy drinking days compared to the placebo group. Topiramate patients reduced their heavy drinking by 2 to 3 days at follow-up.

Among topiramate patients, brain activation changes in response to alcohol cues were associated with changes in craving and heavy drinking.

When topiramate patients were assessed, there was a positive relationship between changes in neural responses to alcohol cues and craving in response to alcohol cues, with greater reductions in the orbitofrontal cortex associated with greater reductions in alcohol-cue elicited craving. With respect to heavy drinking days, a greater reduction in neural activation of the ventral striatum in response to alcohol cues at 6-week follow-up was associated with a greater reduction in heavy drinking days across the same time period. There was no relationship between brain activation and craving or heavy drinking days among the placebo group. This pattern of results remained the same even after controlling for age and baseline drinking measures.

Image BY: Neuroscientifically Challenged, n.d. The ventral striatum, depicted above as a red dot, is located more toward the center or deeper regions of the brain (i.e., medial). The ventral striatum is made up of two small subregions (not depicted), called the nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle. The image above shows a sagittal section of the brain (as if someone were facing with their forehead pointed toward the left, and the brain were cut in half from forehead to the back the head) with the ventral striatum located near, but more medial than, the orbitofrontal cortex.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Studies like this help us better understand the ways in which medication treatments for substance use disorders produce their effects. Characterizing the effects of topiramate on the brain and its relationship to alcohol-related behaviors can help further our understanding of how this medication, traditionally used for epilepsy, works for alcohol use disorder. Doing so can ultimately help guide decisions around FDA approval of topiramate, as well as the development of novel medications to better treat alcohol use disorder and help patients initiate and maintain recovery.

Compared to placebo, topiramate resulted in greater reductions in brain activation in response to alcohol cues, which was correlated with greater reductions in alcohol craving and heavy drinking days. Reduced brain activity was seen in the ventral striatum and orbitofrontal cortex, regions which are important for processing rewards and behavioral responses to alcohol and other drug cues. The ventral striatum plays an important role in reward processing and the process by which alcohol-related behaviors are reinforced. Activation of the ventral striatum is seen when noticeable cues in one’s environment trigger an expectation of reward, such as anticipating alcohol consumption upon seeing an advertisement for alcohol or passing by a bar on the way home. The orbitofrontal cortex receives information from the ventral striatum and other regions involved in the reinforcement of substance use and related behaviors and plays a key role in guiding motivated behavior. Activity of this region is thought to reflect long-term memory of associations between cues and rewards (e.g., associating alcohol use with reward and pleasure).

Given that topiramate patients had reduced activity in these two brain regions in response to alcohol cues, topiramate might act to reduce the importance of alcohol cues and the motivation to consume alcohol by reducing the perceived value (i.e., salience) of alcohol cues and, in turn weakening the learned association between alcohol cues and reward. This could ultimately lead to a reduction in alcohol use. Whereas other medications for alcohol use disorder appear to work by dampening the rewarding effects of alcohol through blocking opioid receptors (naltrexone) or by reducing biobehavioral stress (acamprosate), topiramate seems to induce it’s effects by reducing the salience of alcohol cues.

It is important to remember, however, that these results are correlational, meaning that cause and effect between brain changes and improved alcohol outcomes cannot be determined and additional research is needed to determine if the exact mechanisms by which topiramate works. Nonetheless, the medication appears to be associated with beneficial neural and behavioral changes that support recovery from alcohol use disorder and the observed relationships among the variables tested in this study were consistent with predictions. Topiramate’s ability to reduce reactivity to alcohol cues might better equip individuals to avoid relapse by reducing alcohol craving and heavy drinking behaviors that can occur among alcohol use disorder populations in response to alcohol cue exposure.

The behavioral findings of this research also confirm the results of a number of other studies which demonstrate topiramate’s ability to reduce heavy drinking and craving. Evidence suggests its ability to curb craving may be more effective in patients whose craving is characterized by obsessive thoughts about drinking and who find their drinking to be driven by automatic behaviors (i.e., more severe alcohol disorder). Though all individuals in the current study had an alcohol use disorder diagnosis, their disorder severity was not reported, and future research will help clarify whether or not brain changes and corresponding behavioral changes occur uniformly across treatment populations with various levels of clinical severity.

Additional investigation will help characterize the longer-term effects of topiramate on alcohol consumption, craving, and corresponding brain changes, all in the context of its side effect profile, to determine the full potential of this medication. As an innovative neuroimaging study of topiramate among patients with alcohol use disorder, this work lays the foundation for subsequent research that can ultimately help inform topiramate’s utility for alcohol use disorder treatment, as well as its mechanism of action to guide the development of novel medications that work in similar but potentially more effective ways.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study was a sub-study of a prospective randomized pharmacogenetic trial of topiramate’s efficacy to reduce the frequency of heavy drinking and only included a very small subset of participants in the trial. Furthermore, the authors did not correct their statistical analyses to account for multiple comparisons, which can lead to false positive results. Results should be interpreted in light of these limitations.

- To be included in the trial, all individuals needed at least an 8th-grade reading level, an IQ of 80 or greater, and no evidence of cognitive impairment. Moreover, individuals were excluded from participation if they had a serious psychiatric illness, co-occurring drug use disorders or current drug use (i.e., opioids, stimulants), histories of physical health conditions that can affect cognition (e.g., seizures or stroke), or were receiving treatment with a psychotropic medication. Thus, outcomes may not translate to individuals with polysubstance use and more clinically severe psychiatric presentations, or to those with greater cognitive impairment or injury.

- 3. Though a reduction in craving and heavy drinking days was reported among the topiramate group, the average scores were not reported, and it is therefore difficult to determine the clinical significance of these changes over time and relative to one another.

BOTTOM LINE

Characterizing the effects of topiramate on the brain and its relationship to alcohol-related behaviors can help improve our understanding of how it works, inform policy (e.g., potential FDA approval) and ultimately guide the development of novel medications to better treat alcohol use disorder and help patients initiate and maintain recovery. This study found that, compared to placebo, topiramate resulted in greater reductions in brain activation in response to alcohol cues, specifically in areas implicated in reward processing (ventral striatum & orbitofrontal cortex). Moreover, reduced brain activation to alcohol cues among topiramate patients was correlated with greater reductions in alcohol craving and heavy drinking days. Given the reported benefits of topiramate treatment for alcohol use disorder and the few neurobehavioral investigations of its underlying mechanisms, more research is needed to identify how exactly it works and how long its benefits last to support long term recovery outcomes. Other neuroimaging techniques (e.g., positron emission tomography) will also help us better understand which brain chemicals are specifically affected by topiramate and how they might work to promote recovery.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Though typically used as an anti-seizure medication, topiramate also shows promise for reducing craving and heavy drinking in individuals with alcohol use disorder. Topiramate may act by targeting reward-centers of the brain to reduce the value of alcohol cues and weaken the association between these cues and alcohol-related reward, to help people reduce alcohol consumption. Despite it not yet being FDA approved, some physicians use this medication off-label for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Individuals who have not had success with other treatments might consider speaking to their healthcare providers to learn more about this medication.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Though not yet approved by the FDA for alcohol use disorder treatment, topiramate shows promise for reducing neurobehavioral responses to alcohol cues, which could ultimately reduce drinking and craving to support recovery. Additional research will help inform the populations for which the medication works best and the mechanisms by which it produces its benefits.

- For scientists: Additional research is needed to replicate and extend these findings and determine the patient characteristics that influence medication response. Positron emission tomography investigations could help characterize the neurochemical effects of topiramate, and alterations in neurotransmitter systems that ultimately drive neural activation and inhibition to influence behavior. Investigation of longer follow-up periods will also help to determine the long-term benefits of topiramate treatment for alcohol use disorder.

- For policy makers: Preliminary evidence suggests that topiramate reduces alcohol craving and heavy alcohol use among individuals with alcohol use disorder. Studies like this help us better understand the mechanisms underlying these effects, providing additional evidence of their influence on brain areas that are key players in addiction and the relationship between brain responses and alcohol-related behaviors. Such studies can ultimately inform policies around FDA approval of medications for alcohol use disorder and facilitate new medication discoveries. Given that this is the first brain imaging study of topiramate for alcohol use disorder, additional funding is needed to replicate and expand these findings, and to determine the populations for which topiramate might be most effective and the duration of its benefits.

CITATIONS

Wetherill, R. R., Spilka, N., Jagannathan, K., Morris, P., Romer, D., Pond, T., … & Kranzler, H. R. (2021). Effects of topiramate on neural responses to alcohol cues in treatment-seeking individuals with alcohol use disorder: Preliminary findings from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology, 46(8), 1414-1420.