An underused tool for alcohol use disorder: Evaluating the effectiveness of extended-release, injectable naltrexone

Naltrexone is one of three FDA-approved medications for alcohol use disorder. It is usually prescribed in a once-per-day oral dose that can prove challenging for some patients, for example those insecurely housed. This meta-analysis summarizes studies that examined the effectiveness of monthly, extended-release (XR) naltrexone injections.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) currently approves 3 medications for alcohol use disorder (AUD): naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram. Of the 3 medications, studies have shown naltrexone to be slightly more effective in increasing number of days abstinent and decreasing reoccurrence of use, while one meta-analysis found acamprosate slightly more effective in promoting overall abstinence. However, the size of naltrexone’s effectiveness in reducing alcohol use varies considerably across studies. Further, naltrexone is most often prescribed in an oral dose taken once per-day. Some patients—for example, people who are insecurely housed—struggle to adhere to a daily medication schedule, limiting the medication’s real-world effectiveness. The variable effects found in different studies, as well as the difficulties with adherence, may explain why only a small percentage of people receiving treatment for alcohol use disorder are prescribed naltrexone in the United States.

Naltrexone is also available in an extended-release injectable formulation (XR naltrexone, also known as the brand name “Vivitrol”). Since XR naltrexone is injected monthly, it may help resolve the challenges of day-to-day adherence. Until recently, XR naltrexone has not been widely available given its high price (approximately $1200 per month versus $100 for oral naltrexone), the reluctance of insurance companies to cover its cost, and limited evidence supporting its effectiveness. However, recently some state Medicaid programs have begun to support its use by granting it “preferred drug status.” The study team identified all randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of XR naltrexone and pooled their findings to evaluate its effectiveness in reducing drinking days and heavy drinking days when combined with common psychosocial interventions such as therapy.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a systematic review and meta-analysis. In other words, the authors conducted an extensive review of the research literature to identify all of studies relevant to evaluating the effectiveness of XR-naltrexone. They then used statistical tools to synthesize the findings in order to derive overall estimates of XR-naltrexone’s effectiveness across all of the available studies. The authors followed the guidelines for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). PRISMA provides a checklist of 27 items to help ensure that authors provide a transparent and accurate account of how the review was conducted, what criteria they used to select studies, and how the authors accounted for biases in the literature, for example the tendency to only publish positive results.

The authors searched databases for articles published from January 1966 to September 2019. Two investigators independently screened titles and abstracts of all items. They selected all randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trails that assessed the efficacy of XR-naltrexone on alcohol use. Studies were excluded if they were not randomized or blinded or if XR naltrexone was not compared with a placebo. They also excluded studies that did not measure drinking frequency or heavy drinking. They evaluated the studies for common forms of bias and contacted the corresponding author in cases where the data was not readily available or clear.

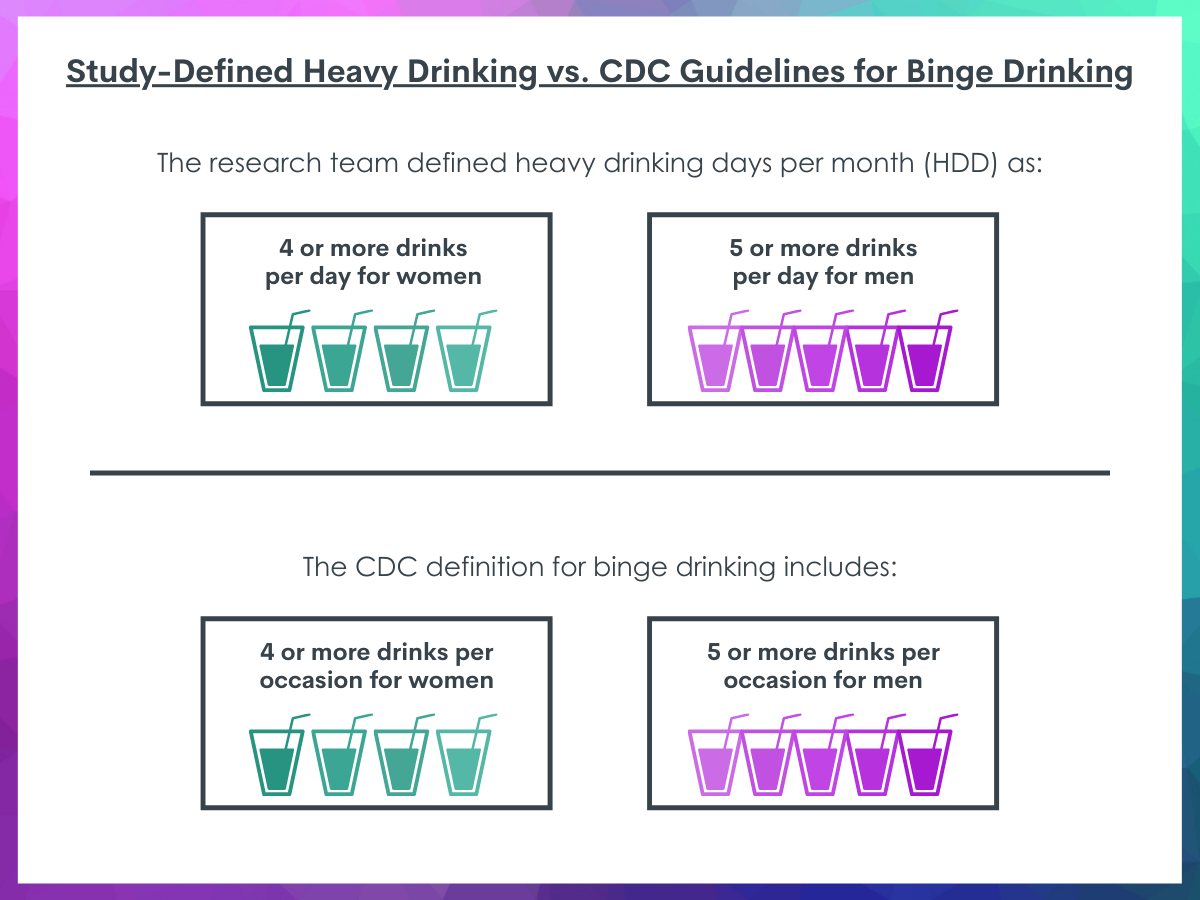

The main outcomes of interest were number of drinking days per month and number of heavy drinking days per month. (Heavy drinking was defined as four or more standard drinks a day for women; five or more standard drinks a day for men. This definition is similar to how the Center for Disease Control defines Binge Drinking). As a secondary outcome, they calculated the number of participants with no heavy drinking days per month and the proportion achieving abstinence for the entire period of the study. In a separate analysis (called a “subgroup analysis”), they compared trials that required participants to be abstinent before the beginning to studies that did not. They also compared studies lasting longer than 12 weeks with studies lasting 12 weeks or less.

The final analysis included 7 studies incorporating a total of 1500 participants. All 7 studies were conducted in outpatient settings in Europe or the United States. It is important to note that all 7 studies also included a common psychosocial intervention (e.g., therapy) in addition to XR naltrexone or placebo. Therefore, the results are a comparison of XR naltrexone with psychosocial intervention compared to placebo with psychosocial intervention. XR naltrexone is administered as a monthly intramuscular injection at a dose of 380 milligrams. However, two studies included in this analysis used lower doses. To evaluate the potential influence of lower doses, the research team conducted a separate statistical analysis (a “sensitivity analysis”) that excluded the two studies utilizing the non-standard lower dosing.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Reduction in drinking days, but no difference on return to any drinking.

The authors found that participants in the XR naltrexone group drank, on average, 2 fewer days per month than in the placebo group.

Only 3 studies included data on return to any drinking (in other words, “relapse”) during the study period. Analysis showed that participants on XR naltrexone were no less likely to return to any drinking than the placebo group.

Small reduction of heavy drinking days.

All 7 studies included data on heavy drinking days. The analysis shows that patients on XR naltrexone on average had 1.2 fewer heavy drinking days per month than patients receiving placebo. In the 4 studies that tracked reoccurrence of heavy drinking (i.e., “relapse”), there was no difference between the XR naltrexone and placebo groups.

Largest effect on non-abstinent study participants.

The authors carried out a subgroup analysis comparing studies that required participants to abstain from all drinking for a period before the beginning of the trial (“lead-in abstinence”) and those that did not. Studies requiring lead-in abstinence reported a 1.09 reduction in heavy drinking days. Trials not requiring lead in abstinence saw an average decrease in 2 heavy drinking days. In other words, when abstinence was a requirement for participants to enter the study, XR naltrexone was no better than placebo. But when abstinence was not required, XR naltrexone outperformed placebo.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Although they might at first appear modest, these results are important. This systemic review and meta-analysis found that the addition of XR naltrexone to common psychosocial interventions for alcohol use disorder resulted in 2 fewer drinking days and 1 to 2 fewer heavy drinking days per month. In the placebo group, psychosocial interventions plus placebo effects (e.g., psychological benefits from expecting a medication to be helpful) reduced heavy drinking days from approximately 20 to approximately 7 days a month. The additional 2-day reduction added by XR naltrexone brings heavy drinking days down to 5 days a month. In theory, an additional 2 days of abstinence could be enough to delay serious health consequences, such as cirrhosis, by up to a year. In more human terms, these 2 additional days might be days where an individual does not miss work or avoids potentially harmful behaviors, such as driving while intoxicated.

In contrast to the most recent meta-analysis of oral naltrexone, this study found no significant difference in return to heavy drinking days for XR naltrexone (in other words, “relapse”). The earlier study of oral naltrexone found an effect on return to heavy drinking in 1 in 12 cases. However, the two reviews included studies based on different criteria, including different dose strengths of naltrexone and lengths of treatment. It is therefore possible that no true difference exists between the impact of oral and XR versions of naltrexone on return to heavy drinking. Prior reviews of oral naltrexone have found a small to moderate effect on drinking and heavy drinking in individuals with alcohol use disorder, but also substantial heterogeneity of effect size across studies. This inconsistency may be one reason why oral naltrexone is underused. The stability of effect size found in this meta-analysis should reassure prescribers that XR naltrexone is an effective addition to psychosocial treatment.

This study challenges the current recommendation of only using XR naltrexone in individuals able to achieve abstinence before treatment. Studies that did not require lead-in abstinence, in fact, showed stronger results in this meta-analysis. The authors suggest that this outcome might reflect a learning model of addiction. According to their theory, naltrexone may reduce the rewarding effects of alcohol and the experience of drinking while on naltrexone might allow a patient to learn that alcohol is no longer rewarding. Another possible interpretation is that participants that were able to initiate abstinence prior to research studies possessed other factors that supported reduction in days drinking and therefore adding the medication benefited them less. The authors observe that the effectiveness of XR naltrexone in non-abstinent groups is consistent with some studies of oral naltrexone. However other studies of oral naltrexone (where participants had concurrent cocaine use disorder or comorbid metal illness) found no effect on heavy drinking. More research is needed on this question.

All 7 studies evaluated the effectiveness of XR naltrexone combined with a standard psychosocial intervention for alcohol use disorder. As a result, they may underestimate the effectiveness of XR naltrexone as a stand-alone intervention. The psychosocial interventions on their own are effective, reducing heavy drinking by an average of 13 days. The limited additional effectiveness of XR naltrexone might represent a “ceiling effect”: a situation where increasing doses of an intervention or combining two types of interventions have a progressively smaller effect. Further research is necessary in order to evaluate XR naltrexone as a stand-alone intervention. More research is also needed to determine whether there is a better medication-patient fit for some patients than others. Such research could help tailor approaches to particular patients and enhance both the effectiveness and efficiency of clinical care for alcohol use disorders.

A major barrier to the prescription of XR naltrexone is cost. The retail cost of XR Naltrexone is about $1200 a month compared to an average retail cost of $100 a month for oral naltrexone. This cost difference makes it unlikely that XR naltrexone will be widely adopted as a first line medication, although more state Medicaid programs granting it “preferred status” could alter the situation. For patients who have tried oral naltrexone and found daily adherence difficult, or whose objective circumstances (such as insecure housing) make a daily medication schedule challenging, XR naltrexone is a viable alternative.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- All studies included in this meta-analysis examined XR naltrexone combined with a common psychosocial intervention for AUD. However, the authors did not report on the kind of psychosocial interventions utilized in the evaluated studies. Further research is necessary to evaluate XR naltrexone’s effectiveness as a stand-alone intervention in the absence of psychosocial support.

- None of the available studies of XR naltrexone lasted longer than 6 months. Further longitudinal research is necessary to evaluate long-term effectiveness.

- The studies were limited to the effect of XR naltrexone on days drinking and heavy days drinking per month. Future research should examine other outcomes, such as psychosocial outcomes and other clinical outcomes.

- The results of this meta-analysis were driven by the two largest studies. Their removal from the analysis of drinking days per month resulted in negligible effects sizes and the loss of statistical significance.

- Most study participants screened positive for moderate or severe alcohol use disorder. Future studies could control for severity to determine whether people with more severe conditions benefit more or less from the medication.

BOTTOM LINE

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrates that XR naltrexone, combined with standard psychosocial interventions for alcohol use disorder, reduces the number of heavy drinking days per month by 15 days on average. For people who struggle with adhering to the daily medication schedule of oral naltrexone or other medications for alcohol use disorder, XR naltrexone is a viable alternative. Although more public insurers have begun to cover XR naltrexone, the cost is currently prohibitive compared to the oral version of the same medication. This analysis supports XR naltrexone’s wider utilization in the treatment of alcohol use disorder and its coverage by public and private insurers. More research is needed on the long-term effectiveness of XR naltrexone and how useful it might be as a stand-alone intervention without accompanying psychosocial treatment delivery.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Studies have shown that naltrexone is effective in helping some people reduce their heavy drinking and preventing return to use. However, the effectiveness of naltrexone varies considerably between individuals, and it does not help everyone. Furthermore, naltrexone is normally prescribed in a once-daily oral tablet. Taking medication daily can be challenging for some individuals. This systematic review examined studies of once-per-month, extended-release naltrexone injections (XR naltrexone). It found that, combined with other forms of support such as therapy, XR naltrexone contributed to an average 15-day reduction of heavy drinking days a month. While XR naltrexone may also be effective on its own, we do not currently have evidence that demonstrates its effectiveness without accompanying therapy or other forms of support such as mutual-help meetings.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: There are currently 3 FDA approved medications for alcohol use disorder (AUD): naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram. Only a small minority of people receiving treatment for AUD are prescribed these medications. In the case of naltrexone, this reluctance might reflect the variation and fairly small magnitude in effectiveness across studies and the difficulty that some patients have in adhering to a daily medication schedule (for example, people who are insecurely housed). However, there is an injectable, monthly version of naltrexone that would help resolve the adherence issue (XR naltrexone). This systematic review and meta-analysis shows that XR naltrexone, combined with common psychosocial interventions for AUD, consistently reduces heavy drinking days from 20 to 5 drinking days a month. This reduction represents an additional 2 drinking days over the combination of psychosocial intervention and any psychological benefits from receiving a placebo medication. While a modest effect, an additional 2 days abstinent is theoretically enough to delay cirrhosis by a year and could have a real-world impact on quality of life. Multiplied by the number of people seeking treatment for alcohol use disorder annually in the U.S., for example, this effect could result in a savings of approximately 1.5 million person-years of ill health due to cirrhosis alone. XR naltrexone is therefore an evidence-based option for people who have struggled to adhere to oral naltrexone’s daily schedule. At the same time, it is important to communicate to patients that XR naltrexone does not work for everyone, and its effects are modest. Additionally, research has demonstrated the effectiveness of XR naltrexone in combination with psychosocial interventions. Although it may help some people, we currently do not have evidence to support the effectiveness of XR naltrexone as a stand-alone intervention.

- For scientists: This systematic review and meta-analysis pooled seven, double-blinded, randomized control trials that compared a monthly, injectable extended-release naltrexone (XR naltrexone) combined with a common psychosocial intervention for alcohol use disorder with placebo combined with the same psychosocial intervention (interventions varied across studies). It found that XR naltrexone consistently reduced drinking days by 2 days a month and heavy drinking days by 1-2 days a month. While a modest effect, this finding showed low heterogeneity and therefore was more consistent than oral naltrexone, whose effectiveness varies considerably across studies. Further longitudinal research is needed on the effectiveness of XR naltrexone beyond 6 months and the effectiveness of XR naltrexone delivered without an accompanying psychosocial intervention. Further analyses might examine AUD severity as a moderator of benefit or other genotype or endophenotype characteristics that might fit better with XR. The studies involved in this review examined drinking days and heavy drinking days. It is also important that future research XR naltrexone evaluate psychosocial and other clinical outcomes.

- For policy makers: Naltrexone is 1 of 3 FDA approved medications for the treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD). Despite multiple studies that show its effectiveness, it is prescribed by a small minority of addiction treatment providers. This underutilization may reflect the considerable variation in its effectiveness across different studies. It may also reflect the fact that naltrexone is most commonly prescribed as a daily, oral tablet and some patients struggle with adherence (for example, people who are housing insecure), therefore limiting its effectiveness. However, naltrexone is also available in the form of a once monthly injection. This extended review and meta-analysis shows that, combined with standard psychosocial treatments for alcohol use disorder (such as therapy), XR naltrexone reduces number of days drinking by 2 days a month and number of heavy days drinking by 1 to 2 days month. Combined with psychosocial treatment, XR naltrexone consistently reduces heavy drinking days from an average of 20 to 5 drinking days a month. The evidence supports its wider adoption, especially for patients who might struggle with a daily medication schedule. However, the cost of XR naltrexone is currently prohibitive (around $1,200 monthly). Although Medicaid has adopted XR naltrexone as a preferred medication in some states, most insurers only cover the cost of the less expensive oral version. Policies that make XR naltrexone more affordable may improve health outcomes for individuals with alcohol use disorder, especially those with challenges such as unstable housing that make daily medication adherence more difficult.

CITATIONS

Murphy, C. E., Wang, R. C., Montoy, J. C., Whittaker, E., & Raven, M. (2022). Effect of extended-release naltrexone on alcohol consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 117(2), 271-281. doi: 10.1111/add.15572