Connecting veterans with medication for opioid use disorder: Are we doing better or worse?

The Veteran’s Administration (VA) mandates that their facilities make medications for opioid use disorder available for all veterans who receive VA care. Still, the majority of veterans with opioid use disorder have historically not received these medications. This study assessed how commonly VA patients who were diagnosed with opioid use disorder used opioid use disorder medications and whether facilities changed over the course of 2 years in the proportion of patients using such medications.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Military veterans experience higher rates of substance use disorder than the general population and have unique needs due to their military service. Medications like buprenorphine (known more commonly by its brand name Suboxone), methadone, and naltrexone (known more commonly by its monthly injection formula branded Vivitrol) are shown to reduce opioid overdose rates by 70-90% and are also effective for the treatment of opioid use disorder in helping to enhance remission rates. Consequently, these medications are mandated to be available for all veterans who receive care at VA medical facilities. That said, the majority of veterans with opioid use disorder have historically not received these medications. This study assessed the VA’s recent performance in this area, and whether provision of these medicines improved in the VA system from 2016-2017.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Using national VA data from fiscal years 2016 and 2017 (i.e., October 2015 to September 2016 and October 2016 to September 2017), the authors assessed the rate of opioid use disorder medication prescription by calculating the number of patients who received pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder (i.e., methadone, Suboxone, and naltrexone or Vivitrol) divided by the number of patients with a current opioid use disorder diagnosis for each year at each VA facility (N= 129) and examined change from 2016 to 2017. Opioid use disorder diagnoses were derived from patients’ VA medical record, while medication receipt was defined as one or more visits to methadone clinic, and/or one or more prescriptions filled for buprenorphine or naltrexone.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The authors observed that there were 52,763 veteran patients in 2016 and 54,078 veteran patients in 2017 who received a diagnosis of current opioid use disorder.

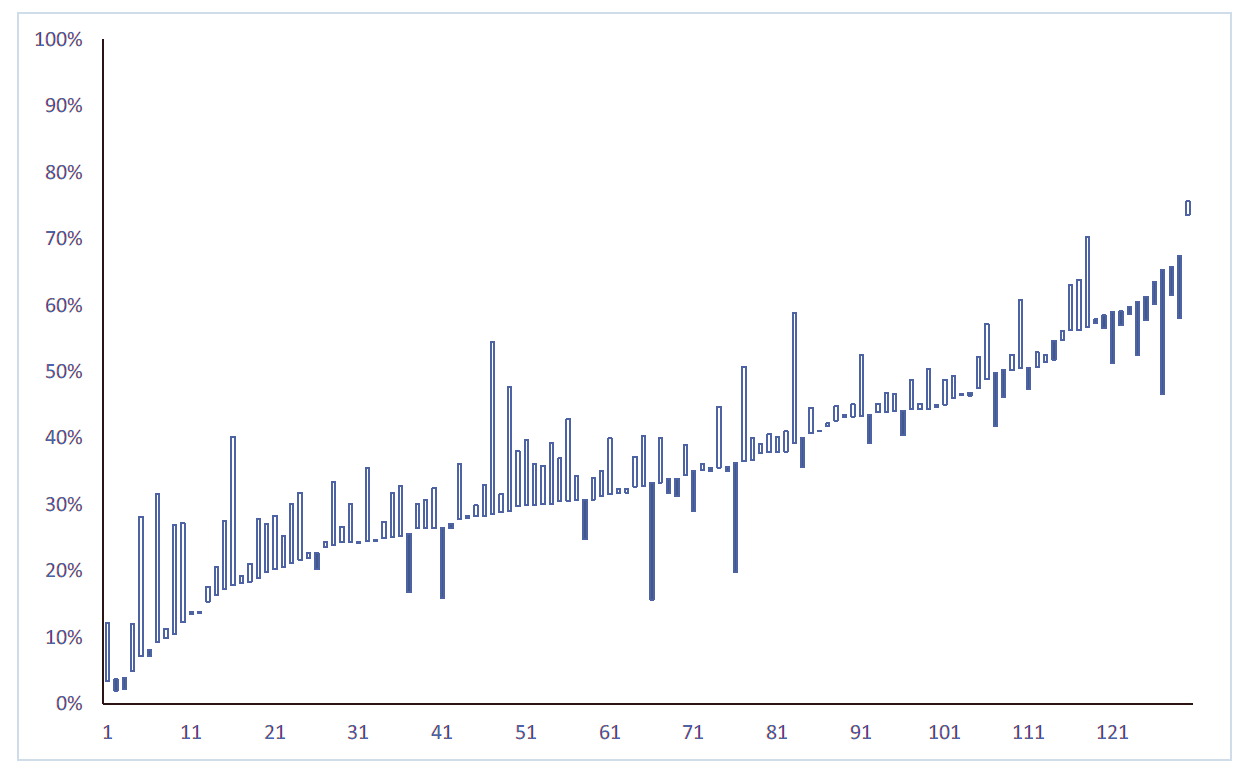

In 2016, the overall rate of receipt of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder was 38% (n= 20,028), with the performance of individual facilities ranging from 3% to 74%. In 2017, the overall rate of receipt of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder was 41% (n= 22,179), with facility-level performance ranging from 2% to 76%. At the facility-level, the change in receipt of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder from 2016 to 2017 averaged 3% and ranged from −19% to 26%.

There were 32 facilities (25% of the total number of facilities in the study) that had a decrease in rates of receipt of pharmacotherapy, 12 facilities (9%) with no change, and 85 facilities (66%) with an increase.

Figure 1. Graph showing change in opioid medication prescription in 129 Veteran’s Administration (VA) health facilities from fiscal year 2016 to 2017. Each line in the graph represents a single VA site. Sites are ordered from lowest to highest rate of receipt in pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder in 2016. The bars display the change in rate of opioid use medication receipt from 2016 to 2017, with unfilled bars indicating a positive change (more medication per-capita) and filled bars indicating a negative change (less medication per-capita).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Nationally, the overall provision of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder at VA facilities increased from 38% in FY16 to 41% in fiscal year 2017 with two-thirds of facilities experiencing an increase over the two-year period. There were, however, wide variations across facilities in level of provision of pharmacotherapy, and the change in provision of pharmacotherapy from 2016-2017. It also appears that these medications are being underutilized in the VA healthcare system, although this is not an issue unique to the VA. 2017 survey data from SAMHSA show that out of all the U.S. facilities they surveyed providing addiction treatment (13,585), only 10% were certified by SAMHSA for the provision of medication therapy with methadone and/or buprenorphine. Further, the proportion of all surveyed addiction treatment facilities providing buprenorphine services was only 29%, while the percentage of addiction treatment facilities providing Vivitrol was 24%. The factors contributing to the lower than desirable uptake of medication for opioid use disorder, in spite of their demonstrated effectiveness for reducing relapse rates and protecting against fatal overdose, are varied and complex. At an individual level, many people with opioid use disorder are against the use of agonist medications like buprenorphine and methadone because they perceive them to adding risk for relapse, are a crutch that detracts from their work in other kinds of therapy and/or 12-Step programs, or see these medications as a continuation of their addiction (i.e., they are still physiologically reliant on opioids). There are also systemic barriers to implementing medications for opioid use disorder such as a shortage of prescribers licensed to prescribe buprenorphine, poor general knowledge about these treatment approaches among clinicians, and insurance reimbursement issues.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Because naltrexone is approved for both alcohol and opioid use disorder, it is possible that some individuals with co-occurring alcohol and opioid use disorders were prescribed naltrexone for alcohol use disorder, and not opioid use disorder. As such, these prescriptions could have been attributed to the treatment of opioid use disorder, when in fact they were written to treat alcohol use disorder.

- Patient beliefs about taking medication for opioid use disorder were not accounted for in this study. It is possible some individuals with opioid use disorder were offered medication but declined. Given many individuals are against taking opioid use disorder medication, this could have led to some underreporting of medication utilization in the study. That is, some individual who were not taking medication may have been doing so because of their own preferences, rather than them not being offered by their VA healthcare providers.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Military veterans experience higher rates of substance use disorder than the general population and have unique needs due to their military service. If you are an individual or family member of an individual receiving care in the U.S. VA system for opioid use disorder and want medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone, but are not receiving them, enquire with your doctor, as they are required to provide these medications.

- For scientists: The U.S. VA system has taken important first steps toward making opioid use disorder medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone available to all patients. At the same time, actual receipt of these medications among veterans with opioid use disorder in the VA system varies widely from site to site. More research is needed to better understand the specific barriers leading to patients not using these potentially lifesaving medications.

- For policy makers: Despite being a standardized, national health care system, the authors’ research highlights the wide disparities in medication provision across VA sites. These kinds of disparities, however, are not unique to the VA system. Policies that increase patients’ access to potentially lifesaving medications like methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone are necessary to combat opioid overdose fatalities and the public health burden of opioid addiction.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Though the authors’ research suggests 41% of veterans with opioid use disorder are receiving medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone, they also reveal many are not, and the wide disparities in medication use across VA sites. It is currently unclear what the exact barriers are to veterans’ use of these medications; whether the barriers stem from patients and providers (e.g., negative attitudes about such medications), or other system factors. Given their potential to save lives and enhance treatment outcomes, understanding these barriers can help inform ways of successfully overcoming such barriers where possible, or otherwise ensuring alternative recovery pathways can be offered.

CITATIONS

Finlay, A. K., Binswanger, I. A., Timko, C., Smelson, D., Stimmel, M. A., Yu, M., . . . Harris, A. H. S. (2018). Facility-level changes in receipt of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder: Implications for implementation science. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 95, 43-47. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2018.09.006