Video visits for substance use disorder on the rise, but still lag well behind those for mental health

Telemedicine is on the rise in mental health, this study compared it to substance use disorder in general and opioid use disorder when possible.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Fewer than one in five people with substance use disorder receive treatment and there is a shortage of providers in rural areas. Telemedicine is when treatment is delivered using telecommunications technology similar to Skype, but designed for secure health care communication. Telemedicine has the potential to expand access to treatment but more quality data is needed to determine the effectiveness and patient satisfaction of telemedicine relative to face-to-face visits. Recent research has shown that telemedicine may increase retention in treatment and effectiveness is similar face-to-face visits. Several regulatory and reimbursement barriers exist regarding the implementation of telemedicine despite recent advances. This study aimed to describe how telemedicine is being used. Specifically, the authors

- Compare growth in service use trends for telemedicine treatment for substance use disorder vs. mental health

- Describe the phase of treatment for which telemedicine for substance use disorder is used (e.g., initial evaluation, established patient visit)

- Describe the degree to which people are using telemedicine for the treatment of substance use disorder in lieu of vs. combined with face-to-face treatment

- Describe the clinician training of providers (e.g., psychiatrist, internist, psychologists, social workers) administering telemedicine vs. face-to-face treatment for substance use disorder and mental health

- Describe patient clinical characteristics of those who seek treatment for substance use disorder through telemedicine vs. face-to-face.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors conducted a retrospective analysis of claims data from 2010-2017 which included privately insured and Medicare Advantage enrollees in a large private health plan. The study included patient records from those who were at least 12 years of age and had a primary or secondary diagnosis of substance use disorder (N=1,914,821). The claim was considered to be a primary mental health visit if the primary diagnosis was mental illness.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

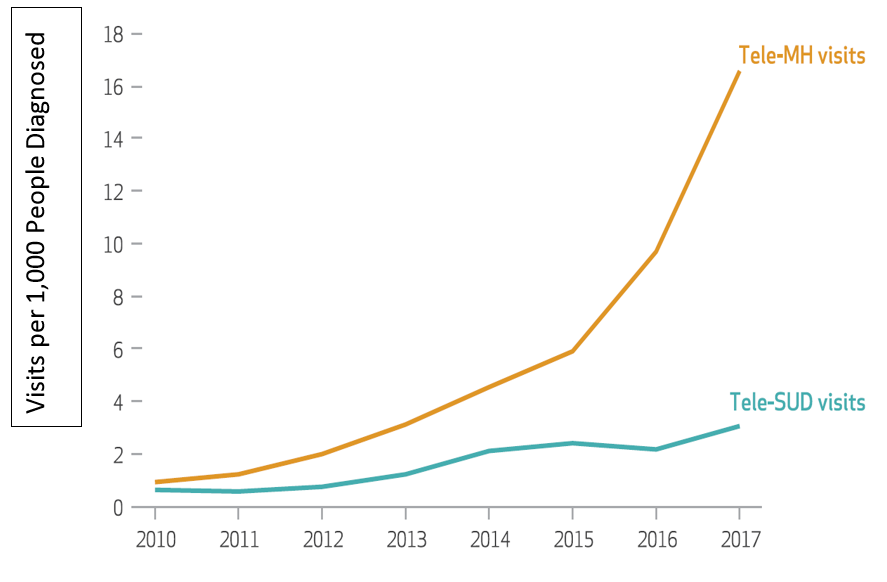

Overall, telemedicine treatment accounted for only .1 percent of all visits for substance use disorder. There was an increase in the use of telemedicine for substance use disorder from 97 visits in the year 2010 to 1,989 visits in 2017 (see Figure 1). In sharp contrast, telemedicine for mental health visits grew from 2,039 to 54,175.

Telemedicine Visits for Substance Use Disorder and Mental Health per 1,000 People Diagnosed. Source: Huskamp et al., 2018

Telemedicine was used for various phases of substance use disorder treatment (from the 81 percent delivered in outpatient settings). New patient initial evaluations consisted of 41 percent of the telemedicine visits, 32 percent were established patient visits, and 11 were unspecified. Only .2 percent were asynchronous interactions (i.e., where the patient submits information and the clinician responds when time permits). Plus, they found that 14% of visits were for psychotherapy for the treatment of substance use disorder.

Ninety-nine percent of telemedicine users for substance use disorder had at least one face-face visits in an ambulatory care setting with 10 face-to-face on average (compared to four for non-telemedicine users). The finding was similar among telemedicine patients diagnosed with opioid use disorder with a median number of one telemedicine visit and 11 face-to-face visits.

Clinical training of telemedicine versus face-to-face providers varied for substance use disorder. Telemedicine providers were mostly family practice physicians or internists (45 percent), psychiatrists (29 percent), social workers (11 percent), and psychologists (1 percent). Face-to-face consisted mostly of social workers (27 percent), family practice physicians or internists (25 percent), psychiatrists (18 percent), followed by psychologists (15 percent). Telemedicine for mental health was 49 percent psychiatrists.

Telemedicine users were more likely to have a moderate or severe diagnosis for substance use disorder (87 percent) compared to non-telemedicine (38 percent). Telemedicine users were also more likely to have an opioid use disorder diagnosis (46 percent) compared to non-telemedicine users (18 percent). This trend was also observed for mental illness with more telemedicine patients being severe (55 percent) compared to non-telemedicine patients (19 percent).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Given relatively low treatment rates among people with substance use disorder, and the severity of the opioid epidemic, low rates of telemedicine for substance use disorder (which were over five times lower than mental health in 2017) may be an opportunity if effectiveness trials can support the use of telemedicine for substance use disorder. Limited implementation of telemedicine models may also reflect financial barriers in reimbursement from insurance companies, the absence of an implementation model that can be used as a guide, or confidentiality concerns. Telemedicine has the capability of reaching underserved populations such rural locations, providing a treatment modality that is unavailable in the patient‘s community, reaching those with transportation barriers, and those seeking privacy during treatment. Surprisingly, telemedicine was most often used with clinically severe patients. In addition, nearly half of telemedicine users for substance use disorder had an opioid use disorder (46 percent) which shows the potential of this mechanism to reach the opioid population and respond to the current epidemic if it were more widely embraced.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study can only inform the prevalence of telemedicine not the effectiveness.

- The results might not generalize to other insured populations such as Medicaid or other public insurances.

- Due to changes in Current Procedural Terminology coding for outpatient visits, it is unknown how many of the non-psychotherapy telemedicine visits focused on medication management.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Telemedicine represents an opportunity to access care from the privacy of your own home. Telemedicine can be used in conjunction with face-to-face visits or as a standalone depending on the provider. Telemedicine is a growing but underutilized tool so it may take time to seek out the right provider of this resource.

- For scientists: Given the rapidly changing policy environment, new models of telemedicine might emerge quickly. For example, telemedicine can be used by non-physicians to monitor a prescribing physician’s patient who are both located a distance away. Telemedicine allows treatment teams to be assembled from across the country (with proper licensure). As this care options evolves, it will be important to closely monitor patterns of telemedicine, cost-effectiveness, and develop a targeted approach if underserved populations are missed. It is still unclear if expanded use of telemedicine will improve outcomes or increase costs but this study found no difference in patients’ out-of-pocket spending between telemedicine and in-person visits.

- For policy makers: Telemedicine for substance use disorder has been a missed opportunity as shown by the contrasting rates of growth in telemedicine for mental health. Telemedicine can be used to access treatment modalities that are not available in a patient‘s hometown, reach patients with transportation barriers, and reach rural populations. This study found that telemedicine for substance use disorder did not necessarily increase the number of people receiving treatment for substance use disorder (i.e., given that 99 percent of patients also had a face-to-face visit which does not suggests a new population of patients was reached). It is unclear if access to telemedicine increased the number of visits people attended (i.e., retention), but the median number of visit was 10 for those using telemedicine (which represents face-to-face and telemedicine visits) compared to four for those who use face-to-face only, but this could also be explained by clinical severity being higher in the telemedicine group.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Telemedicine is a growing model used to facilitate follow-up or support patients in recovery after intensive inpatient or outpatient treatment. Other models include replacing face-to-face treatment with telemedicine, although this approach was used less frequently. The limited evidence supports increased retention and similar effectiveness compared to face-to-face visits. Despite a rapid increase in telemedicine, this study found low use rates overall (.1 percent of all visits for substance use disorder) which is a sharp contrast to the growth of telemedicine in mental health. Furthermore, this study has found that clinically severe patients are the norm in telemedicine for substance use disorder, and primary opioid use disorder is common. Consider if telemedicine can be used to support your patient population by networking with the physicians or counselors needed to support remission and recovery.

CITATIONS

Huskamp, H.A., Busch, A.B., Souza, J., Uscher-Pines, L., Rose, S., Wilcock, A., Landon, B.E., & Mehrotra, A. (2018). How is telemedicine being used in opioid and other substance use disorder treatment. Health Affairs, 37(12), 1940-1947.