What are the Barriers to Seeking Alcohol Treatment?

Alcohol use disorder is a major cause of disease, disability, and premature mortality in the U.S. 29% of Americans will experience an alcohol use disorder at some point in their lifetime, yet only one in five of these individuals will ever receive any treatment.

While perceived treatment need is strongly associated with treatment utilization, only 15-30% of people with a perceived need for treatment actually receive it. Thus, there are factors or barriers that are interfering with patients’ ability to obtain help for their alcohol use disorder.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Since barriers to care may be different for different people, this study examines barriers among subgroups of individuals with alcohol use disorder who had not sought treatment despite recognizing a need for it.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study used data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a nationally representative survey of 43,093 adults in the U.S. collected between 2001 and 2002. Of adults surveyed, 10,004 (23%) had a lifetime alcohol use disorder and had never received treatment. The authors used the following survey question to determine perceived need for treatment:

“Was there ever a time when you thought you should see a doctor, counselor, or other health professional or seek any other help for your drinking, but you didn’t go?”

The authors performed a latent class analysis to identify subgroups of individuals who endorsed barriers to treatment similarly. A latent class analysis is a statistical method for identifying how individuals in a study group together based on certain variables. In this study, participants were grouped based on how they endorsed barriers to treatment.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

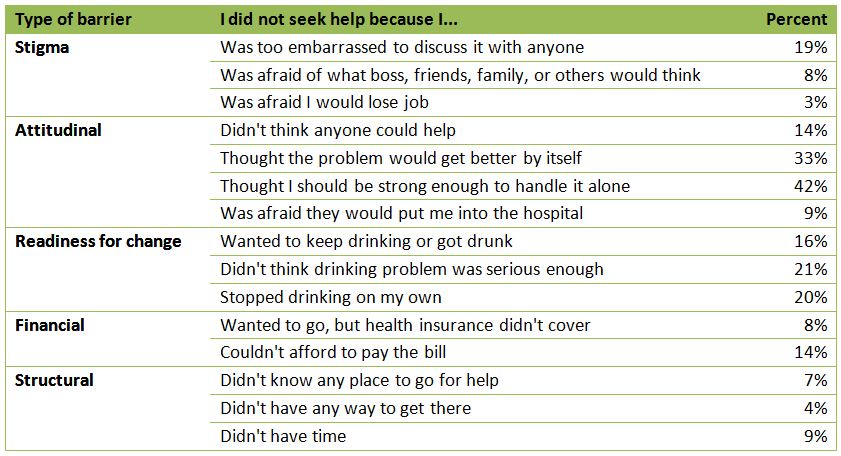

Percentage of participants who endorsed each of the perceived barriers.

The most frequently selected barrier was “thought I should be strong enough to handle it alone”.

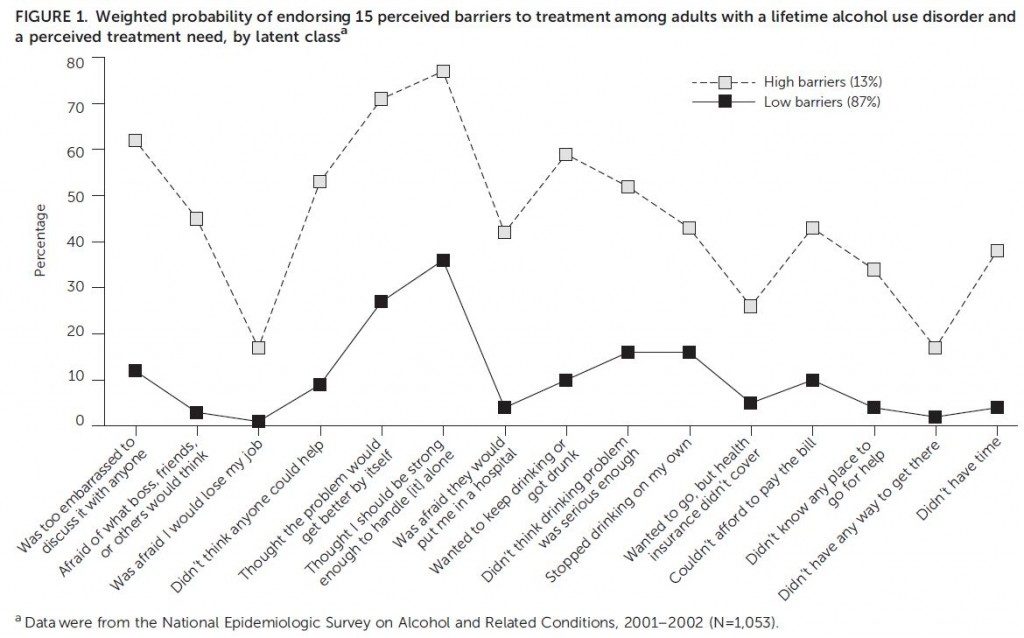

The latent class analysis yielded two groups: a low-barrier class and a high-barrier class.

LOW BARRIER CLASS – A majority (87%) of participants were grouped into the low-barrier class. This class was characterized by moderate likelihood of endorsing attitudinal barriers and a lower likelihood of endorsing the items in other domains (i.e., stigma, lack of readiness to change, financial, and structural barriers). The most commonly endorsed items for this class were: “I thought I should be strong enough to handle it alone” (36%), “the problem will get better by itself” (27%), and “I stopped drinking on my own” (16%).

HIGH BARRIER CLASS – The individuals in the high-barrier class had moderate to high likelihood of endorsing the 15 items across all domains, and for each item, individuals in the high-barrier class were more likely to endorse these barriers than those in the low-barrier class. In particular, this group of participants endorsed attitudinal items, “I thought I should be strong enough to handle it alone” (77%) and “the problem will get better by itself” (77%), at a greater rate than the low-barrier class. They also had a greater propensity to endorse stigma, lack of readiness for change, financial, and structural barrier items than the low-barrier class. For example, 62% endorsed “too embarrassed to discuss it with anyone” compared to 12% in the low-barrier class.

The authors then performed an analysis to determine what factors were associated with being in the high-barrier or low-barrier class, adjusting for age, education, household income, alcohol risk and severity, and comorbid psychiatric condition.

Having an anxiety disorder and having a higher education level were significantly associated with being in the high-barrier class.

This study identified barriers to treatment for alcohol use disorder and determined two groups of people that endorse these barriers differently. The low-barrier class, which was comprised of a vast majority of participants, mainly endorsed attitudinal barriers (e.g., “should be strong enough to handle it alone”), while the high-barrier class had high endorsement of barriers in all domains, including but not limited to attitudinal barriers.

While natural recovery does occur in individuals with alcohol use disorder, particularly those with less severe problems, treatment seeking increases the odds of abstinence and recovery. Understanding these barriers to care can help address issues of treatment access experienced by people in need of treatment.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

By identifying barriers to care among subgroups of people with alcohol use disorder, screening and treatment outreach initiatives can be targeted to the specific needs of the people who will be utilizing these services.

Additionally, addressing these barriers may ultimately increase levels of alcohol treatment utilization, especially among those who perceive a need for treatment but do not seek help. Because studies have shown treatment attendance is associated with lower rates of drinking and increased abstinence, getting more individuals to treatment is likely to translate into increased rates of remission and recovery.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- It is not known if perceived barriers to treatment from NESARC data from 2001-2002 hold true among people with alcohol use disorder today. While rates of treatment seeking have remained steady, barriers may have changed over time.

- Additionally, since the survey was cross-sectional, participants had to retrospectively report their perceptions of barriers to treatment. Depending on how recently they were experiencing these barriers, it may have been difficult to recall this information accurately.

NEXT STEPS

The majority of barriers to treatment for alcohol problems were attitudinal such as thinking the problem would resolve itself or that you should be strong enough to handle it alone. Given that a majority of individuals only endorsed barriers of this nature, this is a key area to explore when designing screening and treatment interventions. The authors suggest that Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) may help identify individuals with alcohol use disorder who otherwise would not have sought treatment. Also, as authors suggest, motivational approaches delivered in primary or mental health care settings may help individuals clarify and enhance their motivation to seek treatment.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: If you have never sought treatment but think you may have a problem, it is possible you agree with some of the barriers described in this study such as thinking that your problem with alcohol will resolve itself. Do not let perceptions of addiction prevent you from pursuing a discussion with a knowledgeable health care provider or stop you from seeking specialty treatment. Many practitioners or programs do one-time consultations regarding need for treatment without requiring you to make any commitments.

- For scientists: This study can also be used to inform development of interventions to encourage help seeking among people with alcohol use disorder.

- For policy makers: This study showed that barriers to treatment are not always structural and financial and may be mostly attitudinal. Policy makers should strongly consider funding for screening and brief intervention in a variety of health care settings to help facilitate getting individuals contemplating treatment into care.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Discussing alcohol use with your patients may help them feel more comfortable with accessing formal treatment. This study was about non-treatment seekers and suggests that patients who fall into this category may be prime candidates for motivational approaches.

CITATIONS

Schuler, M. S., Puttaiah, S., Mojtabai, R., & Crum, R. M. (2015). Perceived Barriers to Treatment for Alcohol Problems: A Latent Class Analysis. Psychiatr Serv, appips201400160. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201400160