What Predicts Residential Treatment Completion?

There are several levels of addiction treatment, varying in terms of the amount of structure, support, & monitoring provided.

Some have argued that residential (i.e., inpatient) options may be needed for patients with more severe substance use disorders (SUDs). Although this remains a hotly-contested empirical question, data suggest one-third of individuals who enter treatment – across levels of care – will not complete it.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Understanding who is at risk for treatment drop-out in both outpatient and inpatient settings may be key to help address these vulnerabilities ahead of time.

Indeed, studies of single treatment programs have helped identify certain risk factors for drop-out, including more clinical severity (e.g., diagnosed with another psychiatric disorder in addition to substance use disorder (SUD), also called co-occurring disorders or dual diagnosis) and homelessness. However, studies of single programs may not capture broader patterns that could help identify overall needs in the health care system.

This study by Mutter and colleagues addressed this gap by investigating protective factors for residential treatment completion and risk factors for drop-out using the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), which assesses addiction programs from across the country that receive state or federal funding.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Researchers used the 2010 SAMHSA Treatment Episode Dataset (Discharge version), capturing 104,999 admissions from states or jurisdictions that reported health insurance status for at least 75% of their discharges. They focused on this health insurance indicator in order to examine specifically the potential impact of this variable in relation to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. The primary outcome was treatment completion (yes/no) where treatment drop-out may have resulted from leaving against medical advice (“AMA”), or where the program terminated the patient for any number of reasons (e.g., not following program rules and policies).

Researchers analyzed the unique influence (i.e., independent of all the other characteristics) of several demographic factors (age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, employment, and living arrangement), clinical factors (prior substance use disorder (SUD) treatment episode; referred by criminal justice system; substance of choice, alcohol vs. other; use of two or more substances; and received medication assisted treatment for opioid use disorder), length of the patient’s treatment program stay (short, defined as 30 days or less vs. long, defined as 31 or more days), and the patient’s type of insurance (private, medicaid, medicare, or uninsured). Analyses controlled for the state in which the patient attended treatment to account for any undue influence this may have had on treatment completion (e.g., more funds in some states dedicated to case workers to help prevent premature treatment drop-out).

Regarding sample characteristics overall, 40% were between 18 and 29, 60% were male, 73% were White and 19% Black, 13% were married, 70% had a high school degree or greater, 88% were unemployed or not in labor force, 31% were referred by the criminal justice system, 68% had at least one prior substance use disorder (SUD) treatment episode, 35% reported alcohol was their substance of choice (28% opioids, 13% marijuana, 11% stimulants, and 9% cocaine), 17% were homeless, and 67% were uninsured (19% had Medicaid, 7% Medicare, and 7% had private insurance).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Overall 71% of the sample completed treatment. The substantial majority of variables examined did, indeed, predict treatment completion. Because the sample was so large, and even small effects of a variable could be statistically significant (i.e., unlikely to be due to chance), it is important to closely examine the size of these effects.

Older age was associated with greater likelihood of completing treatment, with the youngest patients aged 18-20 about half as likely to complete treatment as those 50-54 and 55 and older.

Black and Native American race was associated with about 10% lower likelihood of treatment completion – and Asian/Pacific Islander 25% greater likelihood of completion – compared to White. Higher level of education increased the odds of treatment completion (e.g., 40% greater likelihood of treatment completion for having graduated college compared to not having graduated high school), as did being employed (e.g., 40% greater likelihood of treatment completion for full time employment compared to being unemployed), and having been referred by the criminal justice system (e.g., 75% greater likelihood of treatment completion compared to entering treatment through another referral path).

Receiving substance use disorder (SUD) treatment at least once before, identifying a primary substance other than alcohol, and attending long-term treatment were associated with lower odds of completing treatment. For example, all other factors being equal, patients with opioid as a primary substance were one-third less likely to complete treatment than those with alcohol as a primary substance. Receiving medication-assisted treatment increased one’s odds of treatment completion by 40%.

This study highlights the multitude of factors that might affect whether someone successfully completes residential treatment.

However, this study cannot tell us why the variable influenced treatment outcome. For example, younger age appears to play a role in likelihood of treatment completion.

While this is consistent with several other studies from individual treatment settings (see here and here, for example), it is not younger age, per se, that causes individuals to drop out of treatment prematurely. Rather, younger age is a marker for a host of factors that could account for difficulties with treatment engagement. For example, younger individuals may be less severe than their older counterparts, on average, as they have not had quite as great an accumulation of substance-related physical, psychological, and social consequences. Particularly given the typical ways drinking and other drug use is reinforced by their risky social networks, young adults’ lower severity, in turn, could account for lower motivation to change their substance use and to engage in treatment more generally.

The subsequent clinical implications of this finding, for example, could be that interventions might help increase young people’s recovery motivation, specifically, in order to increase their chance of treatment completion. These data, however, cannot speak to this theory of why younger adults are more likely to drop out.

One important point here is that studies investigating predictors of an important outcome, like treatment completion vs. drop-out, can only identify variables correlated with the outcome, even when they are well designed and control for confounds such as in this one. In other words, in the way that younger age marks biopsychosocial vulnerabilities to treatment drop out, it is best to think of these predictors as markers of other key factors that may or may not be measured in the study.

Another interesting finding showed criminal justice involvement may also predict treatment completion.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Identifying factors that increase (or decrease) the likelihood of treatment completion could inform strategies to maximize treatment benefit.

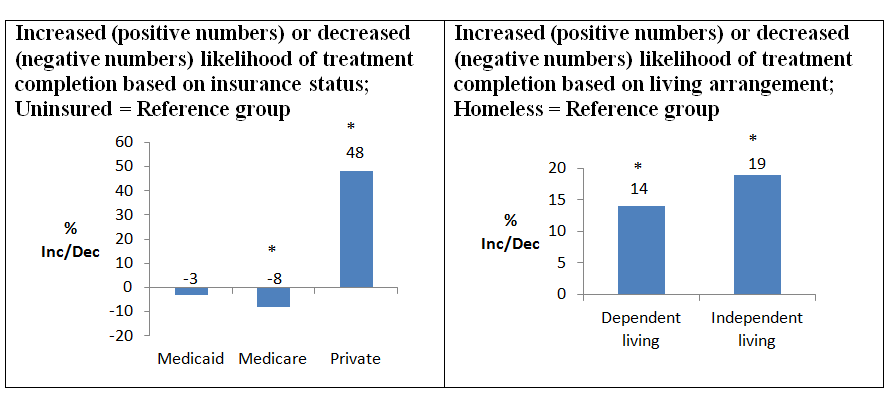

Taken together, these factors contribute to recovery capital, the internal and external resources individuals have at their disposal to help initiate and sustain recovery-related behaviors such as treatment engagement. While it is possible those with private insurance had more coverage, and thus greater likelihood of completing treatment, these data cannot directly speak to this possibility.

Speculatively, because almost 70% of the sample was uninsured, and treatments sampled in the SAMHSA TEDS database receive either state and/or federal funding, it seems unlikely the reason these patients without private insurance dropped-out was that they were asked to leave treatment prematurely due to lack of insurance coverage. Therefore, lack of insurance coverage, in and of itself, seems to be a less likely cause for early treatment drop-out. Assuming having less or no insurance coverage is a marker for lower recovery capital, one potential implication is the importance of reimbursing for services in addition to therapy or medication management visits.

Finally, receiving medication-assisted treatment, such as buprenorphine/naloxone (“Suboxone”) or naltrexone, was associated with a 40% greater likelihood of treatment completion. Though not all patients would be good candidates for medication-assisted treatment due to lack of evidence-based options (e.g., those with cocaine as their primary substance), the sample consisted of 35% alcohol-primary and 28% opioid-primary patients. However, only 2% received medication-assisted treatment.

Two important findings were the differences in rates of completion depending on one’s insurance status and living arrangement, where being uninsured as well as homeless were each predictors of treatment drop-out.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As noted by the researchers, many aspects of the treatment programs in the SAMHSA TEDS were not measured or included in this study. For example, programs that offer comprehensive clinical services including psychotherapy, medication management, and case management in addition to traditional groups like relapse prevention, may be more likely to retain patients. However, this hypothesis could not be tested.

- Also, there are certainly many advantages of using a large sample in research. One disadvantage, is the ease with which researchers can find a statistically significant effect with large samples like the one used in this study (i.e., one that is unlikely due to chance or error). Therefore, the size of the effects are important to truly understand to what degree each factor is actually associated with treatment completion.

NEXT STEPS

There are several possible next steps. First, studies are needed to clarify who should be referred to outpatient treatment and who should be referred to inpatient, or residential treatment. Treatment completion as well as short and long-term substance use outcomes would ideally be considered here.

Second, following up this study with more recent data collected after implementation of the Affordable Care Act might help determine whether individuals who were previously uninsured or had less coverage ultimately receive better substance use disorder (SUD) coverage, and whether such coverage, indeed, makes it more likely for individuals to access and complete addiction treatment.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: This study showed several factors may predict chances of completing treatment, but it cannot speak to whether these factors are causally related to whether one completes or drop out. Many of these factors may simply be a marker of how many resources one has to help begin or continue recovery. More research needs to be done to determine whether addressing one or more of these factors – residing in a stable living environment, for example – increases chances of entering, and staying in recovery.

- For scientists: This study identified predictors of completing treatment, but its design cannot speak to any explanatory processes that account for these significant effects. If taken further, for example, a study like this one could have implications for identifying and addressing ethnicity related disparities in treatment engagement. For example, Blacks and Native Americans were less likely to complete treatments than Whites. Future studies might help tease apart the reasons for this, identify unique needs for these groups of patients, and develop and test approaches to address these health disparities.

- For policy makers: This study showed several factors may predict an individual’s chances of completing treatment, but it cannot speak to whether these factors are causally related. Many of these factors may simply be a marker of how many resources individuals have to help them begin or continue their recovery journey. More research needs to be done to determine whether policies that address one or more of these factors – funds to help increase access to stable housing, for example – lead to increases in the proportion of treated individuals that enter, and stay in recovery.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study showed several factors may predict an individual’s chances of completing treatment, but it cannot speak to whether these factors are causally related. Many of these factors may simply be a marker of how many resources individuals have to help them begin or continue their recovery journey. More research needs to be done to best determine what approaches beyond therapy and medication – strategies to help increase access to stable housing, for example – lead to increases in the proportion of treated individuals that enter, and stay in recovery.