Young Adults, Close Friends & Recovery Outcomes

For a long time, research has shown that the number of substance-using friends someone with a substance use disorder has may affect how well that person does following treatment. But little research has been done to examine the effects of actual exposure to these friends. Does considering the amount of time someone spends with high-risk substance-using friends versus low-risk abstinent/mostly abstinent friends after treatment beyond simply having those friends make a difference in that person’s outcomes over time?

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Someone’s social circle – often called their social network – can influence the likelihood of initiating and sustaining substance use disorder recovery. Also, there is strong scientific support for treatments and other recovery-support services that provide a foundation to help someone decrease the number of drinkers and other drug users in one’s network (e.g., high-risk) and increase the number of abstainers or infrequent users (e.g., low-risk).

For example, in a prior issues of the Recovery Research Institute Bulletin, we highlighted the recovery benefits of Network Support, a 12-step facilitation approach, compared to the mainstay cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). In that study, Network Support benefitted people more than CBT in part because it was better at helping individuals increase the number of abstinent individuals in their network overall.

In this study the authors investigated whether the time spent with these individuals is a meaningful factor in sustaining recovery in addition to a more basic measure of the number of high and low risk friends, which has been studied more often.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Authors used data from 302 emerging adults (ages 18-24) who attended residential substance use disorder treatment. Because authors were interested in how social circles influence abstinence and recovery, they focused on data after individuals left the residential program – including assessments at 3-, 6-, and 12-months after discharge. Social networks in this study focused on friends (rather than family), by asking individuals to list “five of their closest friends.” Patients reported how much each friend used alcohol or other drugs, and how many days per month, on average, they spent with that individual during the assessment period.

Like another study by Kelly and colleagues, authors categorized individuals as:

HIGH RISK: if the patient said the friend engaged in “regular use,” “possible abuse” or “abuse”

LOW RISK: if the friend engaged in “infrequent use,” “did not use” or was “currently abstaining (in recovery)”

This assessment was adapted from the Important People Inventory as well as the Social Support Questionnaire. Authors summed number of friends and number of total days spent with friends for both high-risk and low-risk categories, at each of the assessment period (3-, 6-, and 12-months after discharge). They also subtracted the number of low-risk friends and days spent with low risk friends from high-risk versions of these measures, to get an overall sense of the net risk in one’s social network, and how that relates to abstinence over time. Abstinence was measured by percent days abstinent in the assessment period, a common outcome measure in substance use disorder treatment and recovery research.

Authors compared how strongly days spent with high vs. low risk friends related to abstinence relative to its relationship with the simpler total number of high vs. low risk friends. They hypothesized days spent (i.e., “how much” time with friends) would be more strongly related to abstinence than number of friends (i.e., “how many” friends). They also investigated for each social network variable, whether it was related to abstinence over time, even after adjusting for the effects of demographic characteristics and someone’s abstinence rate when they entered treatment.

A few important details related to the study sample were that most were White (95%), and consistent with many clinical studies on younger individuals with substance use disorder, there were more males (74%) than females (26%). Alcohol and marijuana were patients’ most commonly reported primary substance (28% each), followed by opioid (22%), cocaine (12%), and amphetamines (6%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

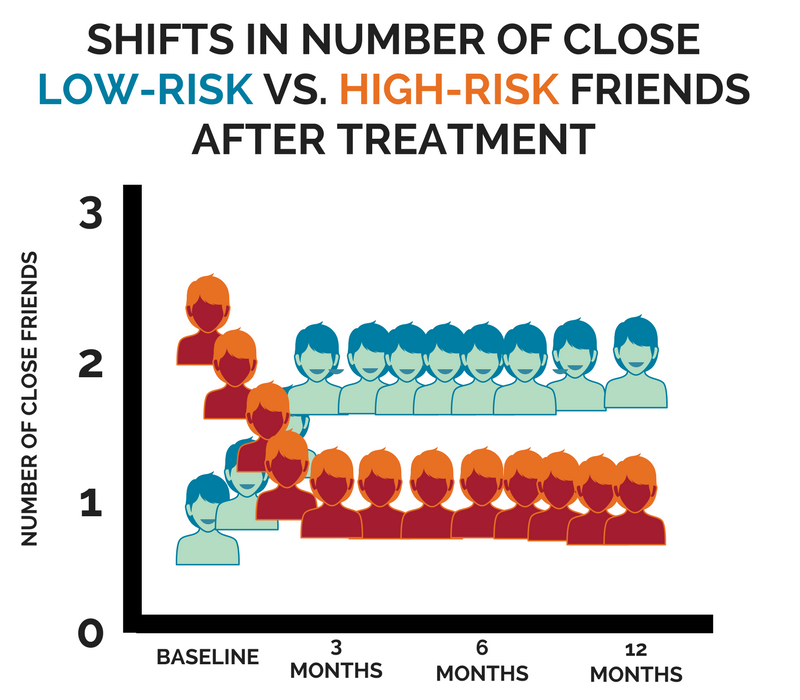

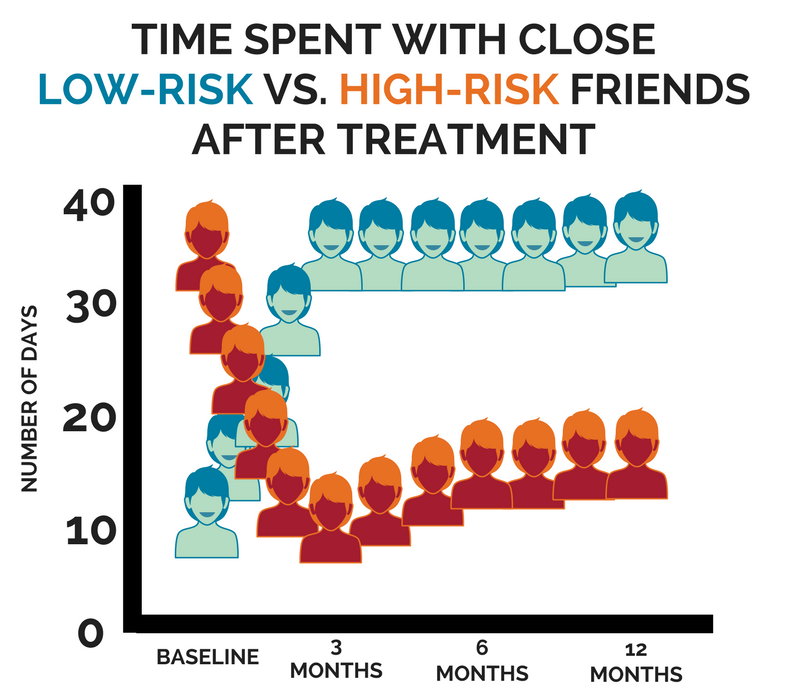

After treatment, the patients sharply shifted their social networks, dropping high-risk friends, and to a lesser degree, adding low-risk friends. These shifts were generally maintained across the post-treatment year.

See figures below adapted from those provided in the study, for these trends over time in the sample. As mentioned earlier, these trends adjusted for percent days abstinent when they entered treatment as well as demographic characteristics, thus controlling for how severe patients were from the outset and demographic individual differences.

Each social factor was related to percent days abstinent in the expected direction – high-risk friendships were associated with worse outcomes and low-risk friendships with better outcomes. Interestingly, for days spent with close friends, these influences increased in magnitude over time; meaning, the negative influence of days spent with high-risk friends increased over time and the positive influence of days spent with low-risk friends increased over time as well.

While these social influences were strongly related to abstinence over time, when investigating whether days spent with close friends was more strongly related to abstinence than just number of friends as was hypothesized, only the impact of high-risk friends in someone’s social circle early on seemed to make a difference. Specifically, days spent with high risk friends at the 3-month follow-up was more strongly related to abstinence than number of high risk friends at that time point. For low-risk friends at the 3-month follow-up, as well as all social influences at 6- and 12-months, the relationships between number of friends and time spent with friends with abstinence were about the same.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

How much time an individual in recovery from substance use disorder spends with close, high-risk and low-risk friends may be equally or more important to their chances of sustaining recovery than whether or not they have high-risk and low-risk close friends. Also, one finding present in other studies that have been done on young adults’ social network influences is that the benefits of low-risk friends aren’t quite as good as the drawbacks of high-risk friends. Some young adults may be unwilling to give up close friends that pose risks to their recovery (e.g., who engage in heavy drinking or any illicit drug use) even if they can acknowledge the risks involved – which is typical for many in this age group where close intimate attachments are highly valued. As the authors suggest, then, encouraging these young adults to spend less time with high-risk individuals could lessen some of this risk. More research is needed to replicate and further understand this potentially important finding.

One other interesting finding was the increase in the size of the social influences over time, as individuals were further out in time from their residential treatment episode. This finding is similar to another set of analyses with this group of treatment-seeking young adults, where the impact of professional continuing care, such as residing in a recovery residence, on abstinence also increased over time. Perhaps the recovery benefits resulting from the development and implementation of relapse prevention coping skills as well as the enhancement of recovery motivation and self-efficacy that accrue during treatment, gradually declines over time for some. This decrement in recovery gains over time might make environmental influences (like those from their social networks) and follow-up recovery support services that much more meaningful in terms of one’s chances of sustaining recovery. If true, this type of pattern highlights the need for clinical and other recovery support service involvement up to, and beyond, 1 year post-treatment, as well as the importance of research that follows individuals for a minimum of 1 year whenever feasible.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- It is possible that a patient could have spent time with two or more close friends in one day – in this study if that occurred it would count as 2 days spent with each of the two friends separately. What happens if someone spends the day with a low-risk and a high-risk friend together? While it is common in research to measure with a simpler approach as was done in this study, the limitation of such an approach is worth noting.

- Some of the more preeminent studies in the area – focusing on adults with alcohol use disorder – have looked not only at the drinking and other drug use of individuals to determine risk, but also how they react to the patient’s drinking, and to the patient’s recovery (sometimes called “attitudinal network support for drinking and recovery”). This study only investigated substance related behaviors of network members to determine risk.

- The study also investigated only five of the patient’s closest friends. It is not known whether asking patients about more individuals (if applicable) would yield the same pattern of results. Some related studies, for example, ask about 10 friends rather than five.

NEXT STEPS

Novel methods of assessment that can get at more fine grained life events – such as spending time with a high-risk and low-risk friends in the same day or at the same time – may improve our understanding of social influences on recovery outcomes. Ecological momentary assessment, which uses portable devices, to ask people about their experiences up to several times per day, is an example of such a method.

Also, this study only measured time spent face-to-face, though young people’s contemporary social lives are a combination of face-to-face and digital (e.g., social media) experience. Preliminary work in the area has indeed shown that both modes of social experience may influence drinking and other drug use among youth. Future studies might investigate the dynamic and complex effects attributable to each of these social network variables.

Finally, studies are increasingly examining the influence of the structure of individuals’ networks (i.e., egocentric social network analyses), and future treatment and recovery research studies might investigate both the composition of one’s network (i.e., the characteristics of network members) as well as its structure (i.e., the density of those connections, meaning the closeness of the social ties around the individual).

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Whether someone’s friends are drinkers or other drug users or not impacts the chances of initiating and sustaining recovery. Reducing the amount of time spent with riskier friends, even if someone does not drop them completely from their social circle, may help lessen the recovery-related risks of maintaining a connection with them.

- For scientists: This study adds to the literature on the role of social networks in substance use disorder treatment and recovery outcomes, suggesting the amount of time one spends with individuals, and their associated risks (e.g., whether they are heavy drinkers or other drug users or not) may also be important to examine. Authors did not investigate both characteristics of friends in the social network and amount of time spent with these individuals in the same models. As study authors allude to, future work might examine these variables in a mediational model, such that the consequences of having riskier friends in one’s social network is explained by the actual time spent with them. There are many other potential future directions for research on the role of social networks in substance use disorder treatment and recovery outcomes, some of which were mentioned earlier in “What are the next steps in this line of research?”

- For policy makers: Whether someone’s friends are drinkers or other drug users or not impacts the chances of initiating and sustaining recovery. Reducing time with riskier friends, even if someone does not drop them completely from their social circle, may help lessen the recovery-related risks of maintaining a connection with them. There are many other potential future directions for research on the role of social networks in substance use disorder treatment and recovery outcomes, some of which were mentioned earlier in “What are the next steps in this line of research?”. Policies that allocate funding for this line of research, including what treatment and recovery support service factors are able to successfully mobilize positive changes in individuals’ social networks, are likely to yield information that can be used to help improve treatment and recovery outcomes.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Whether someone’s friends are drinkers or other drug users or not impacts the chances of initiating and sustaining recovery. Some patients may be unwilling to cut ties with risky individuals in their networks, particularly those who are younger. For these patients, recommending reduced time with riskier individuals, even if one does not drop them completely from their social circle, may help lessen the recovery-related risks of maintaining a connection with them.

CITATIONS

Eddie, D., & Kelly, J. F. (2017). How many or how much? Testing the relative influence of the number of social network risks versus the amount of time exposed to social network risks on post-treatment substance use. Drug and alcohol dependence, 175, 246-253.