Treating youth with opioid use disorder: Can medication keep young people from discontinuing treatment?

Medications for treating opioid use disorder are effective therapeutic approaches for adults, but we know significantly less about their use among youth. This study suggests that youth receiving pharmacotherapy were substantially less likely to discontinue treatment and behavioral services and remained in treatment up to four times longer than youths receiving behavioral treatment alone.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder (buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone) are effective lifesaving therapies that promote successful treatment and enhance recovery outcomes. However, few studies have investigated these medications and their relationship to treatment outcomes among young adult and adolescent populations. Treatment drop-out is relatively high in young adults and adolescents, and these medications have the potential to promote treatment retention (completing treatment rather than dropping out). The current study assessed the prevalence of medication receipt and its relationship to treatment retention among adolescent and young adult Medicaid patients with opioid use disorder.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors conducted a study of treatment and heath-related data from the Truven-IBM Watson Health MarketScan Medicaid Database, which included medical claims for 2.4 million adolescents and young adults ages 13 to 22. Data were collected between January 2014 and December 2015, and represented 11 deidentified U.S. states (all census regions). The study sample included 4,837 adolescents and young adults (median age of 20; 57% female; 76% white) initiating a new treatment episode for opioid use disorder, which was defined as at least 1 inpatient or emergency department insurance claim or 2 outpatient insurance claims. Participants had a primary or secondary opioid use disorder diagnosis (i.e. opioid dependence determined with the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9)), had at least three months of data after diagnosis, and were enrolled in a Medicaid insurance plan. Investigation focused on two types of treatment for opioid use disorder: pharmacotherapy and behavioral health services. Behavioral health services were defined as outpatient, partial hospitalization, and residential/inpatient treatment. Pharmacotherapy included buprenorphine (either with naloxone (Suboxone) or without naloxone (Subutex); here we refer to buprenorphine as ‘Suboxone’ since this formulation is more commonly prescribed than Subutex), naltrexone (oral or long-acting injectable naltrexone), and methadone. In the U.S. Suboxone treatment is approved for individuals age 16 and older, whereas methadone and naltrexone are largely limited to the treatment of individuals 18 and older.

The authors first assessed (1) the prevalence of addiction treatment within 3 months of receiving an opioid use disorder diagnosis (i.e. “timely” addiction treatment). Among those with timely addiction treatment, the researchers also compared the effects of pharmacotherapy (with or without behavioral treatment) versus behavioral treatment alone on (2) retention in treatment (any addiction treatment and behavioral health services) and (3) duration of care. Retention in treatment was defined as the time from initial to final treatment claim and discontinuation of treatment was defined as no treatment claims for 60 or more consecutive days. Analyses controlled for several sociodemographic factors, including age at diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, Medicaid eligibility, pregnancy, depression, anxiety disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, other (non-opioid) substance use disorders, and pain conditions. They also controlled for the level of care received (i.e. outpatient vs. inpatient vs. partial hospitalization) to ensure that they were capturing the effects of medication treatment without the influence of other factors.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

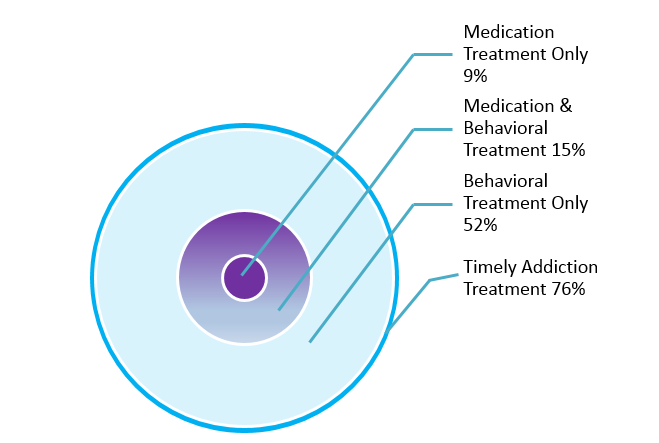

About 76% of adolescents and young adults received addiction treatment within 3 months of receiving an opioid use disorder diagnosis.

- 67% received behavioral treatment alone or in combination with medication

- 33% received outpatient treatment or partial hospitalization

- 34% received residential/inpatient care

- 24% received medication treatment alone or in combination with behavioral treatment

- 19% received Suboxone

- 3% received naltrexone

- 2% received methadone

Figure 1.

Among those who received timely addiction treatment, 71% discontinued treatment. But receipt of opioid use disorder medication was associated with increased likelihood of addiction treatment and behavioral health service retention.

- Compared to behavioral treatment alone:

- Suboxone patients were 42% less likely to discontinue any addiction treatment service and 27% less likely to discontinue behavioral health services

- Naltrexone patients were 46% less likely to discontinue any addiction treatment service and 43% less likely to discontinue behavioral health services

- Methadone patients were 68% less likely to discontinue any addiction treatment service and 53% less likely to discontinue behavioral health services

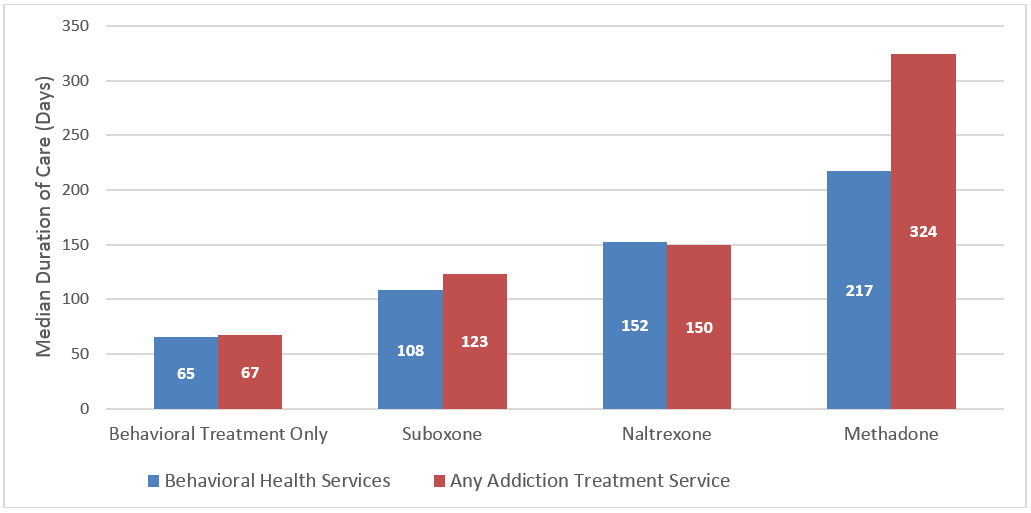

Among those who received timely care, retention in any addiction treatment service and retention in behavioral health services was longer in those who received medication (with or without behavioral treatment) than those who received behavioral treatment only.

Figure 2.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study lends insight to the clinical approaches that are most helpful for adolescents and young adults with opioid use disorder. Although 75% of this population appears to receive treatment within 3 months of a diagnosis, the majority of these individuals are using behavioral health services without opioid use disorder medication. Medication treatment, with Suboxone, methadone, or naltrexone, was associated with greater retention in addiction treatment and behavioral health services over the course of 2 years, compared to behavioral treatment alone. Median retention in care was about 66 days with behavioral treatment only, whereas retention duration was around 4X higher for methadone and 2X higher for Suboxone and naltrexone. With only about 24% of adolescents and young adults receiving these medications, a large proportion of individuals may be at increased risk for treatment discontinuation. Retention in care is a key contributor to positive addiction recovery outcomes and can substantially reduce one’s risk for overdose, with treatment and behavioral health sevices typically offering care for comorbid mental/physical health conditions and harm-reduction services, in addition to addiction-focused treatment. Although medication treatment by itself is not typically talked about as a behavioral treatment, utilizing these services often comes with patient progress check-ups and a level of clinical care, and progress. Randomized controlled trials have previously revealed the shorter-term benefits of Suboxone on treatment retention among adolescents and young adults, and the current study suggests that these benefits extend across longer periods of time and to methadone and naltrexone. Importantly, this study does not suggest that behavioral treatment is ineffective for opioid use disorder but, rather, that medication may offer benefits above and beyond behavioral health services, specifically with respect to treatment retention. With only about 2 in 5 addiction treatment programs for adolescents offering opioid use disorder medication, increased access to these services might benefit adolescent treatment seekers and program retention. However, it is not clear whether increased access would be accompanied by increased use of medication services, given that other factors like medication attitudes and perceptions could play a role in medication treatment seeking. Furthermore, as the authors mentioned, this study was unable to control for the severity of opioid use disorder, and youth with more severe disorders may have been more likely to have been prescribed pharmacotherapy and more likely to stay in treatment for longer durations, which could account for differences in retention prevalence and duration. More research is needed to help clarify these issues. Randomized controlled investigation will help to confirm the current study’s findings, determine how long these beneficial effects last, and if they translate to retention in other less formal addiction recovery services (e.g., 12-step) and across levels of severity.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The study sample was limited to individuals with Medicaid insurance seeking treatment. It is unclear if these findings would apply to adolescents and young adults with other types of insurance or without insurance.

- The authors did not assess whether outcomes differed for those receiving medication treatment with behavioral treatment versus medication treatment without behavioral treatment. Furthermore, discontinuation, as defined in this study, might include individuals who completed shorter-term behavioral treatments without returning to them, so the effect of medication treatment may be somewhat larger in this study than what would be seen if compared to actual treatment ‘drop-out’.

- This study did not capture retention in non-formal service use (e.g., 12-step-based mutual help services) or recovery outcomes after treatment completion. It additionally did not control for disorder severity, which may impact medication prescribing and retention in treatment. Individuals with comorbid substance use disorders were less likely to receive medication treatment, possibly because opioids were not their primary reason for treatment seeking, and this could have underestimated the prevalence of medication treatment, which might be higher in primary opioid use disorder cohorts. Additional research is needed to determine if medication treatment enhances engagement in other addiction services, influences recovery outcomes (substance use, quality of life, etc.), and benefits youth with different degrees of disorder severity.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Medications that treat opioid use disorder, including Suboxone, methadone, and naltrexone, provide significant benefits to recovering individuals, but we know little about them as they pertain to youth. This study suggests that, although 75% of adolescents and young adults received treatment for opioid use disorder, only about 25% received medication treatment. This study also found that medication was associated with an enhanced likelihood of staying engaged in treatment, with medication treated patients receiving services for up to four times longer than youths receiving behavioral treatment alone. Treatment drop-out rates are relatively high among youth and medications for opioid use disorder might help to promote continued treatment enrollment, with the potential to ultimately enhance positive recovery outcomes. Therefore, it may be worthwhile to consider incorporating these medications into the treatment plans of adolescents and young adults. However, additional research is needed given that this investigation was an uncontrolled study of insurance data, limited to Medicaid patients, that was not able to account for self-selection biases and disorder severity.

- For scientists: Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder treatment, including Suboxone, methadone, and naltrexone, have proven to be effective treatments among adults. Relatively less is known about the effects of pharmacotherapy on treatment and recovery success in adolescents and young adults. This study suggests that, 75% of adolescents and young adults received treatment for opioid use disorder, but only about 25% received pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy was associated with an increased likelihood of treatment retention and longer duration – pharmacotherapy recipients were 27%-68% less likely to discontinue treatment and behavioral services, and had service use durations up to four times longer than youths receiving behavioral treatment alone. Given relatively low retention rates among youth and the potential for pharmacotherapies to enhance retention, these findings may have implications for promoting successful recovery outcomes. Randomized controlled investigations are needed to replicate these findings and determine their translation to non-Medicaid patients, retention in other non-formal recovery services, and different degrees of disorder severity. Research is also needed to better understand the mechanisms underlying greater retention with medication treatment, which can ultimately inform approaches for treating individuals opposed to medication.

- For policy makers: Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder treatment, including Suboxone, methadone, and naltrexone, have proven to be effective treatments for opioid use problems. However, this study suggests that, among adolescent and young adult Medicaid patients receiving opioid use disorder treatment, only 25% are receiving pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy was shown to significantly increase retention in treatment and lengthen the duration of treatment engagement over the course of two years. Retention rates are relatively low in youths and only 37% of addiction treatment programs for adolescents/young adults offer opioid use disorder pharmacotherapy. Increasing access to these medications in treatment programs might help facilitate treatment and recovery in this population. However, few high-quality studies of these pharmacotherapies have been conducted in adolescents and young adults. Allocating additional funds to better understand the effects of pharmacotherapies for opioid addiction (methadone, Suboxone, naltrexone) in youths, and the facilitators and barriers to engaging with medications, will undoubtedly improve our nation’s ability to more effectively help the growing population of individuals with opioid use disorder.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorder treatment, including Suboxone, methadone, and naltrexone, are effective treatments in adults. Despite fewer studies among younger populations, the benefits of these pharmacotherapies may well extend to young adults and adolescents. This study suggests that receipt of pharmacotherapy is associated with enhanced treatment retention and duration of care among adolescent and young adult Medicaid patients. Pharmacotherapy recipients were 27%-68% less likely to discontinue treatment and behavioral services (depending on the medication), and had service use durations up to four times longer than youths receiving behavioral treatment alone. Although 75% of youths with opioid use disorder received treatment within 3 months of diagnosis, only 25% received pharmacotherapy. Given relatively low retention rates among treatment seeking youths, these pharmacotherapes may be a useful tool for enhance retention and promoting successful treatment outcomes. However, additional research is needed given that this investigation was an uncontrolled study of insurance data, limited to Medicaid patients, that was not able to account for disorder severity.

CITATIONS

Hadland, S. E., Bagley, S. M., Rodean, J., Silverstein, M., Levy, S., Larochelle, M. R., … & Zima, B. T. (2018). Receipt of Timely addiction treatment and association of early medication treatment with retention in care among youths with opioid use disorder. JAMA pediatrics, 172(11), 1029-1037.