Military Members & Recovery

About 1 in 15 U.S. military veterans suffer from substance use disorder.

In the United States, there is an estimated 2.2 million active service members, in addition to 23 million military veterans. About 1 in 7 U.S. soldiers currently have a opioid prescription. Members of the military have an increased risk for developing substance use disorder compared to the general population (age-adjusted), and this troubling connection is only intensified by deployment and exposure to combat.

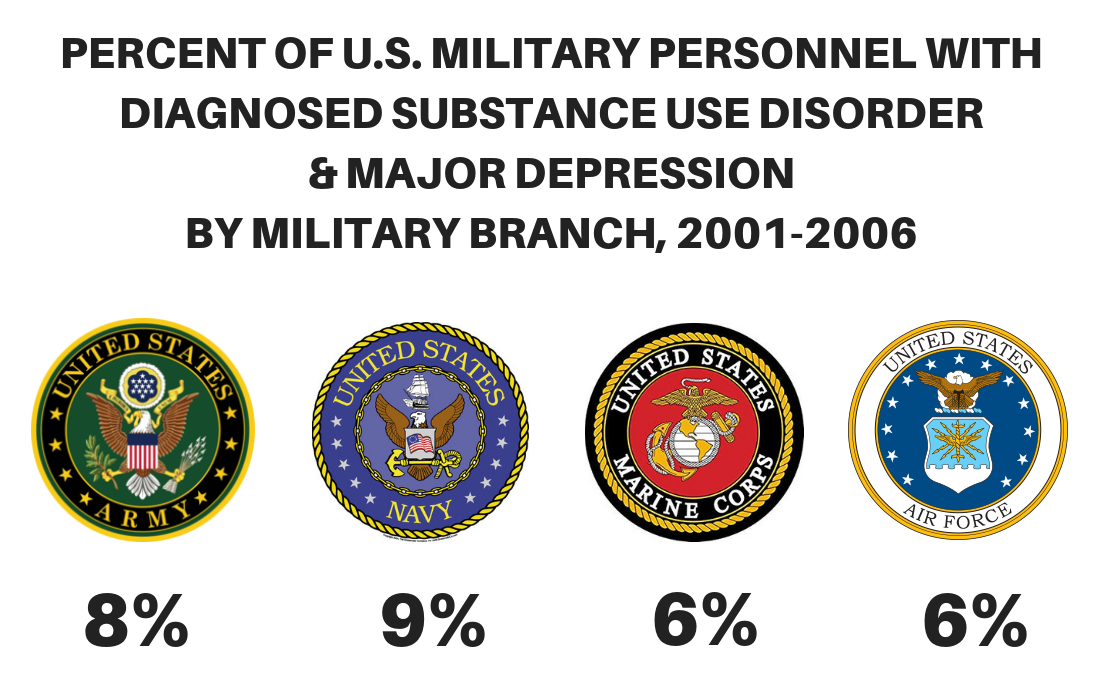

While rates of illicit drug use by members of the military have continued to decrease overtime, alcohol and prescription opioid use remains high. Rates of substance use disorder among military veterans also varies by conflict, ranging from 3.7% among pre-Vietnam-era veterans to 12.7% among veterans of the more recent wars in Iraq and Afganistan.

Substance use disorder is associated with the development of multiple medical conditions and other co-occurring mental health disorders (e.g., depression), increased problems at home and work, increased difficulties in readjustment to civilian life, and an increase in rates of injury, suicide, and morality.

Beyond a heavy personal toll, substance use disorder has a large overall impact and financial toll on U.S. defense operations. With alcohol alone, it is estimated that the U.S. lost $1.2 billion in 2016 due to decreased productivity and medical expenditures resulting from excess alcohol consumption by members of the military.

MILITARY-SPECIFIC SENSITIVITIES:

- DEPLOYMENT

-

History of deployment and combat exposure is associated with increased risk for substance use disorder development. Combat often exposes service members to the death or injury of others, threats to oneself or others, and unknown atrocities.

- One study revealed that witness to fighting, threat to oneself, or atrocities is significantly related to alcohol misuse, even at 3 and 6 months post-deployment.

- Studies from Iraq and Afghanistan have linked military deployments and combat exposure with increased risk for elevated alcohol consumption, binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems, substance use disorder, and depression.

- CHRONIC PAIN

-

“Chronic pain is such a devastating issue. It profoundly affects Veterans, not just physically, but emotionally. It’s strongly associated with depression. It interferes with work, recreational activities and a patient’s social life.”

– Dr. Mathew Bair, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

- Chronic pain affects nearly 60% of veterans returning from the Middle East and 50% of older veterans, compared to only 30% of civilians.

- A 2012 study of more than 141,000 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with both chronic non-cancer pain, and a mental health diagnosis (e.g. PTSD), were more likely to have an active opioid prescription and receiving riskier combinations of opioids and other drugs. Not surprisingly, veterans in this study were more vulnerable to overdose or other opioid-related negative outcomes.

- Until recently, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs was treating chronic pain almost exclusively with opioid prescriptions. The Journal of Pain and Symptom Management reported in 2011 that:

- 3% of veterans shared prescriptions to manage their pain

- 29% of veterans reported alcohol or non-prescription drugs to treat pain

- 35% of veterans used a combination of both alcohol and non-prescription drugs to treat pain

- POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER (PTSD)

-

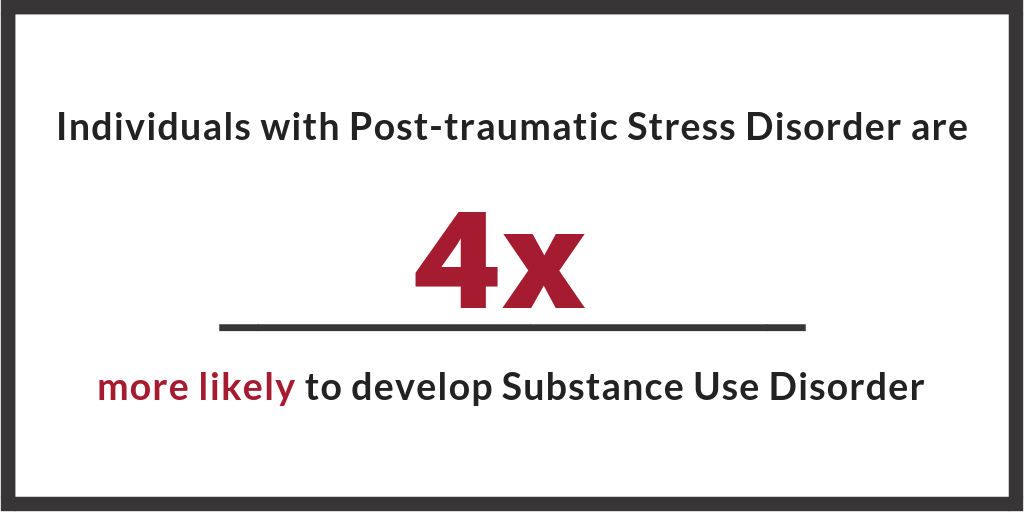

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a condition of persistent mental and emotional stress resulting from injury or severe psychological shock, typically involving disturbance of sleep, constant vivid recall of the experience (e.g. flashbacks), and severe anxiety.

- Over 20% of veterans with PTSD also suffer from substance use disorder.

- Of veterans seeking substance use disorder treatment, nearly 1 out of every 3 suffers from PTSD.

- The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that PTSD affects:

- 31% of Vietnam veterans

- 10% of Gulf War (Desert Storm) veterans

- 11% of veterans of the war in Afghanistan

- 20% of Iraqi war veterans

Personal factors such as previous traumatic exposure, age, or gender, may affect whether or not an individual soldier will go on to develop PTSD from a traumatic event.

SEXUAL TRAUMA

Military Sexual Trauma (MST) is another route by which service members may experience physical and psychological trauma, leading to the development of PTSD. According to U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 55% of female veterans and 38% of male veterans have experienced sexual harassment while serving in the U.S. military.

- TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY (TBI)

-

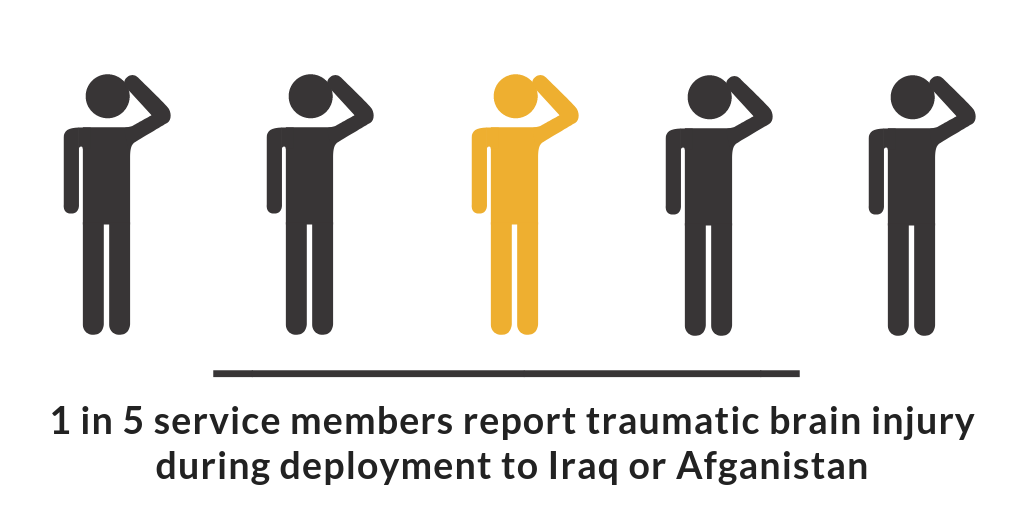

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is the disruption of normal function in the brain resulting from a bump, blow, jolt to the head, or penetrating head injury. Common causes of TBI in military members include:

- An object hitting the head, such as a bullet, flying debris, or falling object.

- Assaults causing either blunt or penetrating trauma, or the head colliding with an object or other person.

- Explosions in which an intense wave of pressure passes through the skull.

Traumatic brain injury is a frequent condition co-occuring with substance use disorder. While evidence is limited, neuro-chemical and behavioral evidence offers support for a causal relationship between traumatic brain injury and addiction development.

- DEATHS OF DESPAIR

-

Deaths of despair refer to deaths by drug, alcohol, and/or suicide.

SUICIDE

Suicide rates in the military were traditionally lower than that of civilians, however, the suicide rate in the U.S. Army began to climb in 2004, surpassing the civilian rate in 2008, and reaching an all-time high in 2012, with mental health and substance use disorders being the leading cause of hospitalizations among U.S. troops.

- One study of military personnel found that:

- Alcohol or other drugs were present in 30% of completed suicides.

- More than 1,100 military members took their own lives from 2005 to 2009, an average of 1 suicide every 36 hours.

- Chronic pain has been found to be associated with an increased risk of suicide. Risk of death by suicide is found to be slightly greater among veterans receiving high-dose opioid prescriptions, versus low-dose opioid prescriptions.

OVERDOSE

- 2006-2009, the U.S. Army reported that more than 45% of the 397 non-combat related fatalities were the result of an alcohol or other drug overdose. Of the 188 accidental or undetermined deaths resulting from alcohol or other drugs, 74% were caused by prescription drugs.

- One study of military personnel found that:

- 20% of high-risk behavior deaths involved alcohol or other drugs.

- One study of military personnel found that:

- CO-OCCURING DISORDERS

-

Co-occurring disorders, also known as comorbidity or dual diagnosis, signify the prevalence of both a mental health condition and substance use disorder.

Common mental health diagnoses to military members with substance use disorder include:

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Mood disorders (e.g. bipolar)

- Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): The rate of PTSD and opioid use disorder among veterans increased from 2.5% in 2004 to 3.4% in 2013.

Co-occuring disorders need to be addressed, as risk of fatal opioid overdose rates are 3x higher for those diagnosed with depression, and 6x higher for those with serious mental illness.

- MILITARY CULTURE & STIGMA

-

Military members and their families are culturally unique, with distinct behavioral healthcare needs that may not be understood by the wider community or within the general population.

Military culture is widely seen as supportive of alcohol consumption, but stigmatized with regards to other drugs, and the general development of substance use disorder from alcohol or other drugs.

- Heavy drinking is traditionally an accepted custom in military work culture, to foster recreation, reward hard work, ease interpersonal tensions, and promote cohesion and camaraderie.

- There is a wide availability of inexpensive alcohol on military bases, which is correlated to behaviors of binge and underage drinking.

- Workplace culture in the military is also of concern, specifically around the stigma related to problem substance use and fear of negative consequences related to seeking help. Although active duty troops and their families are eligible for care from the U.S. Department of Defense and Department of Veterans Affairs, significant numbers choose not to access these services for fear of stigma, discrimination or potential repercussions that would negatively affect ones military career.

- READJUSTMENT

-

Reintegration after deployment can be challenging for both servicemen and their families. Readjustment to normal life can be a difficult process after incidence of emotional or physical injury, and time apart. Research from 2013 found that 44% of soldiers returning from deployment faced challenges with the transition back to civilian life, challenges that included the onset of problematic substance use.

Reintegration and readjustment is not only difficult for military members themselves, but also for their families.

- Research has found that length of deployment is cumulatively associated with higher rates of mental health diagnoses among U.S. Army wives.

- Compared to national samples, children of deployed military personnel are found to have increased emotional difficulties with family, peers, and in school.

- Combat exposure and longer deployments are also associated with higher divorce rates. Research has shown an uptick in divorce rates among those with deployments to conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

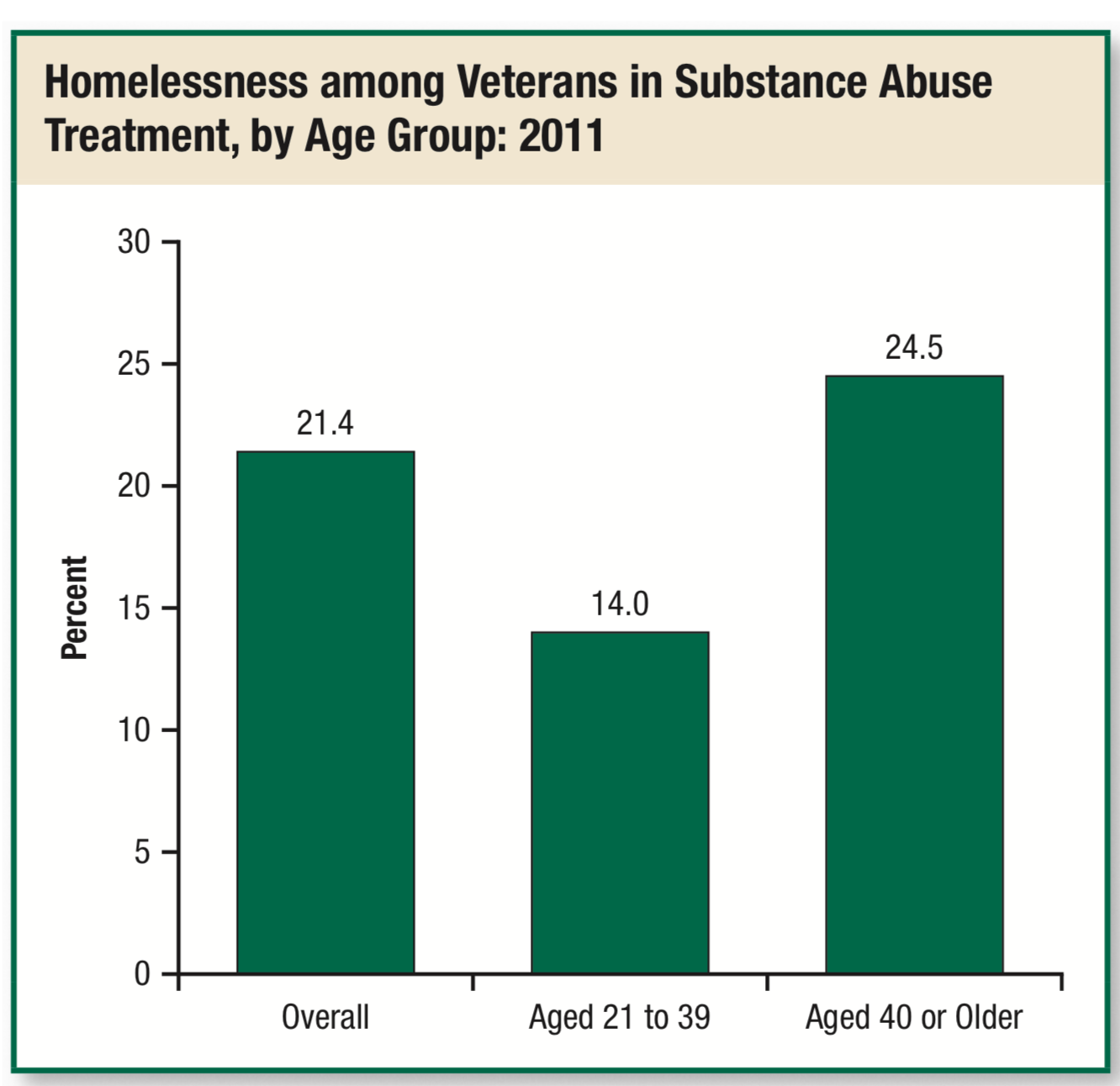

- HOMELESSNESS

-

Military veterans make up a large portion of homeless adults in the U.S. The number of homeless veterans is expected to continue to increase as a result of current military conflicts. Overall, 70% of homeless veterans have a problem with substance use.

- The Departments of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Veterans Affairs (VA) reports that in 2009 alone, nearly 76,000 veterans experienced homelessness, and more than 136,000 veterans spent at least one night in a homeless shelter.

- A SAMHSA 2014 TEDS (Treatment Episode Data Set) report found that out of all veterans actively in treatment for substance use disorder, 21% were also homeless at the time of treatment.

SUPPORTIVE MEASURES FOR MILITARY MEMBERS IN TREATMENT

- MEDICATIONS

-

During recent conflicts in the Middle East, the military increased its use of prescription medications for the treatment of chronic pain and other health conditions, using opioids as a primary intervention. In 2009 alone, military physicians wrote almost 3.8 million prescriptions for pain management. The development of substance use related problems is found to increase with the number of opioid prescriptions per patient, so predictably, rates of opioid prescription misuse have increased. Military populations however, have seen a greater increases than in the general population, generating increasing concern among military, health, and political leaders on all levels.

Recently, the U.S. military began taking steps to address opioid use on both a national and local level.

ON A NATIONAL LEVEL:

- The military altered physician prescribing patterns, targeting the supply of available opioid prescriptions, in hopes of reducing the potential for substance use disorder development or medication diversion among patients. The Army, for example, has implemented changes that include:

- Limiting the duration of prescriptions for opioid pain relievers to 6 months.

- Having pharmacists monitor patient medications, especially when patients are receiving multiple prescriptions.

- They began the Opioid Safety Initiative for the management of opioid therapy medications. This program measured key clinical indicators from 2012 to 2014, showing a 13% drop in patients receiving opioids, and a 15% drop in patients receiving long-term opioid therapy. Also as a part of this initiative, over 70,000 more military patients were drug tested to guide treatment decisions.

- An ‘Opioid Dashboard” was developed by both the VA’s Office of Research and Development and the VA Office of Pharmacy Benefits Management to track and monitor prescriptions and dosages to reduce the number of veterans receiving high-dose or multiple prescriptions.

ON A MORE LOCAL SCALE:

- Individual medical centers have been rolling out their own programs. The VA in Minneapolis began the Opioid Safety Initiative, providing greater emphasis on non-opioid pain-management strategies, like yoga and exercise. The center witnessed a 94% decrease in oxycodone prescriptions after program implementation.

MEDICATIONS FOR TREATMENT OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER

Pharmacotherapy can also play an important role in the treatment and management of substance use disorders by reducing withdrawal symptoms and cravings.

There are 3 medications that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for alcohol use disorders:

- Naltrexone

- Acamprosate

- Disulfiram.

There are 4 medications approved by the FDA for opioid use disorders:

- Methadone

- Buprenorphine

- Naltrexone

- Extended-release injectable naltrexone

There are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of cocaine or marijuana use disorders.

- The military altered physician prescribing patterns, targeting the supply of available opioid prescriptions, in hopes of reducing the potential for substance use disorder development or medication diversion among patients. The Army, for example, has implemented changes that include:

- PSYCHOTHERAPY

-

Behavioral interventions for the management of substance use disorder, generally involves short-term, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions, focusing the identification and modification of maladaptive thoughts and behaviors associated with addiction (e.g. craving, substance use, or relapse).

Other behavioral interventions include client-centered, motivational interviewing approaches, which focus on increasing motivation and engagement with treatment to reduce substance use, and twelve step facilitation, which systematically links patients to, and encourages active participation in, community-based 12-step mutual-help groups.

- TRAUMA-INFORMED CARE

-

Trauma is a contributing risk factor in developing substance use disorder. What happens directly after the traumatic event can play a critical role in whether an individual goes on to develop PTSD. Stress can make the development of PTSD more likely, while social support can decrease the likelihood.

Treatment of both substance use disorder, and any associated trauma together, have been found to increase long-term positive patient outcomes.

COMPONENTS OF TRAUMA-FOCUSED TREATMENT INCLUDE:

- Grief or loss counseling

- Peer support groups

- Individual or group talk therapy (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy)

- Exposure or desensitization work

- Pharmacotherapy: medications to decrease symptoms

- Holistic practice: mindfulness techniques, relaxation, yoga, meditation, acupuncture

- Coping skill development: emotional regulation, cognitive restructuring (often gender specific coping skills)

- MILITARY-SPECIFIC SERVICES

-

Military members and their families are culturally unique, with distinct behavioral healthcare needs that may not be understood by the wider community or within the general population. Substance use disorder services should be accessible, culturally competent, trauma-informed, with a special emphasis on reintegration.

Addiction treatment for military personnel needs to address co-occurring mental and physical conditions unique to within this population, such as the increased risk for depression, trauma, physical injury, and chronic pain.

- A 2012 report prepared for the Department of Defense (DoD) by the Institute of Medicine recommendations that the U.S. military improve addiction treatment by increasing the use of:

- Evidence-based treatment interventions and expanding access to care.

- Broadening insurance coverage to include effective outpatient treatments.

- Better equipping healthcare providers to recognize and screen for substance use problems so they can refer patients to appropriate, evidence-based treatment when needed.

- A 2012 report prepared for the Department of Defense (DoD) by the Institute of Medicine recommendations that the U.S. military improve addiction treatment by increasing the use of:

- CHANGING CULTURE

-

The 2012 IOM Report recommeded that to address substance use disorder in the military:

- Develop a culture of confidentiality around substance use disorder, to stem the reluctance of military members to seek services and treatment out of fear.

- Increased focus on destigmatizing substance use problems, especially from drugs other than alcohol.

- Broadening insurance coverage to include early intervention and screening for substance use disorder.

- Implementation of measures such as limiting access to alcohol on military bases.

RESOURCES FOR MILITARY MEMBERS

- Homelessness Resource Center: help prevent the pipeline from homelessness to substance use disorder

- SAMHSA Guide for: treating substance use disorder patients with traumatic brain injury

- Tricare: health care program of the U.S. Department of Defense Military Health System, providing civilian health benefits for U.S Armed Forces military personnel, veterans, and their families.

CITATIONS

- RESEARCH CITATIONS

-

- Bray, R. M., Pemberton, M. R., Hourani, L. L., Witt, M., Olmsted, K. L., Brown, J. M., & Scheffler, S. (2009). Department of Defense survey of health related behaviors among active duty military personnel(2008)(No. RTI/10940-FR). Research Triangle Institute.

- Bray RM, Pemberton MR, Lane ME, Hourani LL, Mattiko MJ, Babeu LA. Substance use and mental health trends among U.S. military active duty personnel: key findings from the 2008 DoD Health Behavior Survey. Mil Med. 2010;175(6):390—399.

- Bonn-Miller, M. O., Harris, A. H., & Trafton, J. A. (2012). Prevalence of cannabis use disorder diagnoses among veterans in 2002, 2008, and 2009.Psychological Services, 9(4), 404.

- Cunningham, M. K., Henry, M., & Lyons, W. (2007). Vital mission: Ending homelessness among veterans. National Alliance to End Homelessness, Homelessness Research Institute.

- Harwood, H.J.; Zhang, Y.; Dall, T.M.; et al. Economic implications of reduced binge drinking among the military health system’s TRICARE Prime plan beneficiaries. Military Medicine174(7):728–736, 2009. PMID: 19685845

- Hyman, J., Ireland, R., Frost, L., & Cottrell, L. (2012). Suicide incidence and risk factors in an active duty US military population.American journal of public health, 102(S1), S138-S146.

- Ilgen, M. A., Bohnert, A. S., Ganoczy, D., Bair, M. J., McCarthy, J. F., & Blow, F. C. (2016). Opioid dose and risk of suicide.Pain, 157(5), 1079.

- Kline A, Falca-Dodson M, Sussner B, et al. Effects of repeated deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan on the health of New Jersey Army National Guard troops: implications for military readiness. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):276—283.

- Lan, C. W., Fiellin, D. A., Barry, D. T., Bryant, K. J., Gordon, A. J., Edelman, E. J., … & Marshall, B. D. (2016). The epidemiology of substance use disorders in US Veterans: A systematic review and analysis of assessment methods.The American journal on addictions, 25(1), 7-24.

- Meadows, Sarah O., Charles C. Engel, Rebecca L. Collins, Robin L. Beckman, Matthew Cefalu, Jennifer Hawes-Dawson, Molly Doyle, Amii M. Kress, Lisa Sontag-Padilla, Rajeev Ramchand, and Kayla M. Williams, 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.

- National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). The CBHSQ Report: Spotlight, 1 in 15 Veterans had a substance use disorder in the past year. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) 2015.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Substance Abuse in the Military. (2018, October 25). Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/substance-abuse-in-military

- Shen, Y. C., Arkes, J., & Williams, T. V. (2012). Effects of Iraq/Afghanistan deployments on major depression and substance use disorder: analysis of active duty personnel in the US military. American Journal of Public Health, 102(S1), S80-S87.

- Skipper, L. D., Forsten, R. D., Kim, E. H., Wilk, J. D., & Hoge, C. W. (2014). Relationship of combat experiences and alcohol misuse among US special operations soldiers.Military medicine, 179(3), 301-308.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Veterans and Military Families. (2018, October 25). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/MilitaryFamilies

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2003-2012. The TEDS Report: Data Spotlight. Rockville, MD: 2014.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research & Development. VA research on Substance Use Disorders. Retrieved from https://www.research.va.gov/topics/sud.cfm.

- Teeters, J. B., Lancaster, C. L., Brown, D. G., & Back, S. E. (2017). Substance use disorders in military veterans: prevalence and treatment challenges. Substance abuse and rehabilitation, 8, 69.

- Wilk JE, Bliese PD, Kim PY, Thomas JL, McGurk D, Hoge CW. Relationship of combat experiences to alcohol misuse among U.S. soldiers returning from the Iraq war. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108(1-2):115—121