Stages of Recovery

THIS SECTION INCLUDES:

- Transtheoretical Stages of Change Model

- The Life Course Perspective

- The Hierarchy of Needs Perspective

Transtheoretical Stages of Change Model

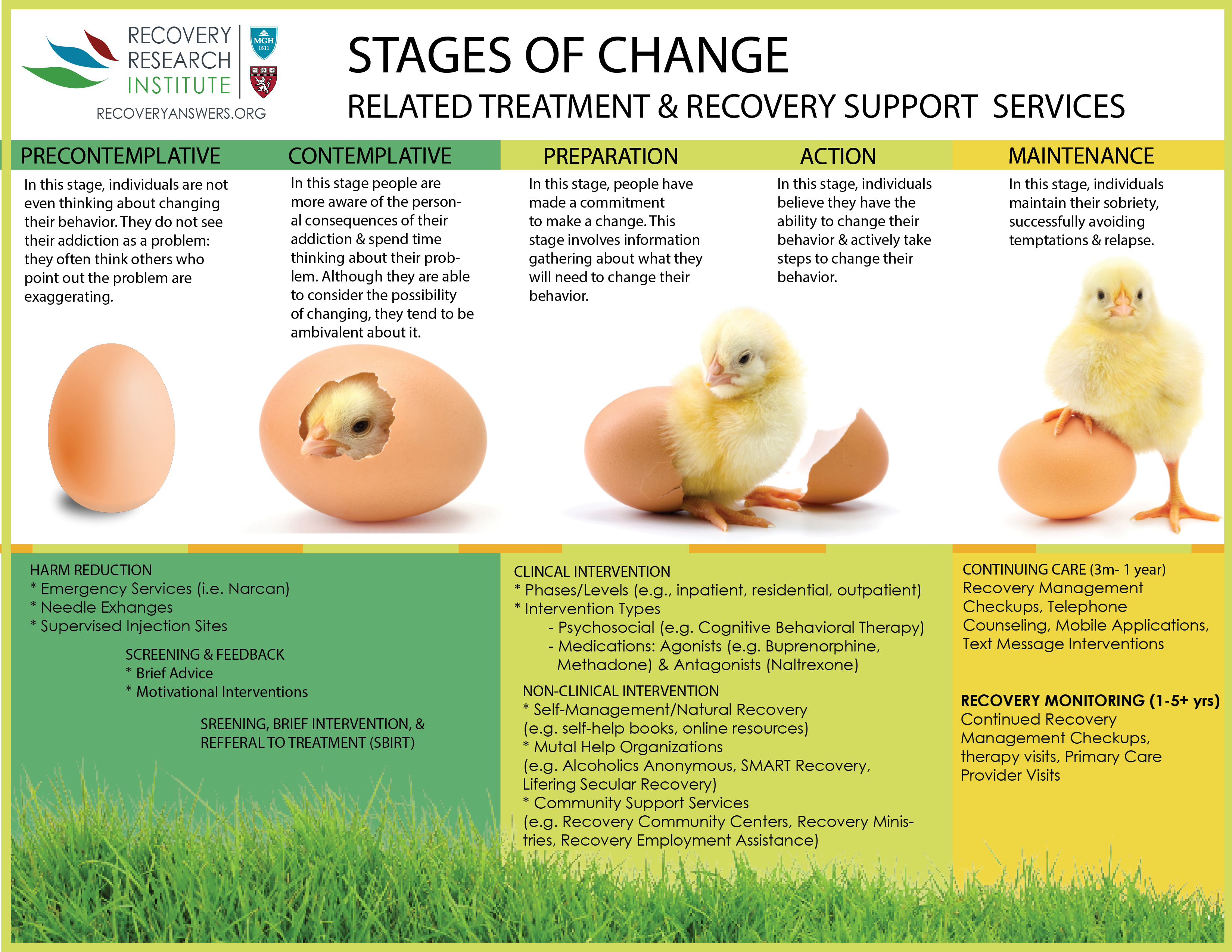

A prominent model of behavioral change that cuts across theories – The Transtheoretical Stages of Change Model – serves as a useful way to understand this change process. The different stages of change necessitate different recovery strategies.

THERE ARE FIVE STAGES:

- PRE-CONTEMPLATIVE

-

As illustrated by the hatching chick diagram above, before starting the change process toward recovery individuals with substance use disorder are in the “pre-contemplative” stage. While they do not yet recognize having a substance-related problem, other people around them often do notice a potential problem.

- CONTEMPLATIVE

-

Typically with an accumulation of negative consequences and feedback from people in their lives, they begin to consider that problems arising in their life could be related to substance use – the “contemplative stage.” During this time, individuals wonder if it might help to reduce or quit using.

Known as “precovery” by recovery research expert William White, several types of interventions are appropriate during the pre-contemplative & contemplative stages.

The goals of these interventions range from strategies aiming to help keep people safe and address the broader public health consequences of substance use (“harm reduction”; e.g., spread of infectious diseases like hepatitis C and HIV) to strategies aiming to enhance their motivation to change (e.g., motivational interviewing).

Only 11% of individuals that meet substance use disorder criteria receive specialty addiction treatment each year, and most of these people do not feel they have a problem or that they need formal addiction services to help them change. So these “pre-covery” approaches often cast a wide net, and are appropriate to use in general (i.e., non-specialty) health care and community settings, such as county hospitals and community health programs.

Although often separated traditionally from substance use disorder treatment and recovery systems, these services are without question integral pieces of a public health approach to addressing addiction, and, by association, are ideally included in an overall model of recovery management.

- PREPARATION & ACTION

-

As individuals decide to take active steps to change their substance use – during “preparation” and “action” stages – the focus shifts to clinical and non-clinical interventions. Pages in the Recovery 101 section highlight several different types of clinical interventions, including both psychosocial strategies and medications, and the scientific evidence for these treatment approaches. While scientific evaluations of these interventions occur in particular clinical settings, for the most part programs can deliver these clinical interventions at any level of care, ranging from standard outpatient to long-term residential treatment.

- MAINTENANCE

-

Even for people who initiate and sustain recovery, it can take many recovery attempts over the course of several years 9+ years. Once individuals make that initial change and establish a period of early remission (i.e., 3 months), how well they can maintain and build on that change is key – during the “maintenance” stage.

Given that there are dozens of psychosocial treatments and medications that can help people reduce or quit using over the short-term, many have argued that how well treatment programs and public health systems support the continuation of change (continuing care (also called “aftercare”), just after an acute treatment episode, and recovery monitoring, over the course of the following several years) is among the field’s greatest challenges.

To paraphrase recovery scientist and scholar Keith Humphreys:

Given the long-term propensity of problem recurrence during substance use disorder remission – at least for the first several years – developing & testing ways to extend treatment models, rather than how to intensify them, is likely to produce a more fitting approach to addressing addiction & its myriad consequences.

State-of-the-art approaches to help extend benefits can range from targeting the maintenance of substance use disorder remission and recovery as early as 3 months, through multiple years, and in some cases, for the remainder of an individual’s life.

The Life Course Perspective

As outlined by addiction scientists Yih-Ing Hser and M. Douglas Anglin, substance use disorder recovery is not a “one-size-fits-all” proposition. Different factors influence the onset of addiction, as well as remission and recovery. The life course perspective – suggesting the factors affecting substance use disorder onset and recovery depend on age and other developmental considerations – is one useful model to understand how different approaches are needed to help different people achieve and sustain remission.

- READ MORE ON THE LIFE COURSE PERSPECTIVE

-

For example, compared to older adults, younger adults have higher rates of substance use disorder (SUD) and other hazardous drinking. Younger individuals in or seeking addiction recovery tend to have less access to recovery-supportive people and environments which may play a role. In fact, the most common precursor to relapse for young people are social situations where alcohol and other drugs are present. The salience of drinking and other drug use in their social ethos, and the more modest accumulation of substance-related consequences compared to older adults, on average, also explains why they are likely to begin a recovery attempt with more ambivalence about actually changing their alcohol or drug use.

In terms of their substance use disorder recovery needs, therefore, young people may need greater attention to developing skills that help them access recovery support. In parallel, compared to older individuals beginning a recovery attempt, they might need more ongoing attention to their motivation for reducing or quitting substance use because abstinence and recovery is not being naturally reinforced as much by people in their social networks.

The Hierarchy of Needs Perspective

Just as individuals’ substance use disorder recovery needs might be different depending on their life course stage, those needs may also be different depending on their recovery stage. What one needs to sustain substance use disorder recovery will be different depending on if they have 3 weeks versus 3 months versus 3 years, and so on in recovery.

- READ MORE ON THE HIERARCHY OF NEEDS PERSPECTIVE

-

Based on his work with addiction treatment patients, substance use disorder recovery expert Terence Gorski outlined six recovery stages each with distinct goals.

Click here to view the Hierarchy of Needs Recovery Stages Model

Indeed, there are emerging qualitative data based on retrospective interviews with people in long-term recovery (i.e., they report on their past experiences) in support of this theoretically-grounded model of recovery over time.

Similarly, from the more general perspective of psychologist Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, for example, early on, the recovery process may necessarily focus on strategies to remain abstinent, consistent with Maslow’s model goals of attending to physiological needs and safety. As individuals are able to meet those needs, they may be able to focus more on expanding their social life and enhanced personal growth – attending to “love and belonging” and “self-esteem,” and ultimately toward becoming their best selves and achieve “self-actualization.”

IN SUMMARY

While more research is needed, recovery models remain an effective means for understanding change behavior and the process of moving from active addiction into long-term recovery.

- CITATIONS

-

Gorski, Terence T. “Recovery: A developmental model.” Addiction and Recovery 11.2 (1991): 10-15.

Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47(9), 1102-1114. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102